Supplement to Probabilistic Causation

Common Confusions Involving the Common Cause Principle

The Common Cause Principle (CCP) says that whenever we have two events A and B such that:

- P(A & B) > P(A)P(B),

and neither A nor B is a cause of the other, then there will be a common cause, C, of A and B, satisfying the following conditions:

- 0 < P(C) < 1

- P(A & B | C) = P(A | C)P(B | C)

- P(A & B | ~C) = P(A | ~C)P(B | ~C)

- P(A | C) > P(A | not-C)

- P(B | C) > P(B | not-C).

In this supplement, we attempt to dispel some common confusions involving the CCP.

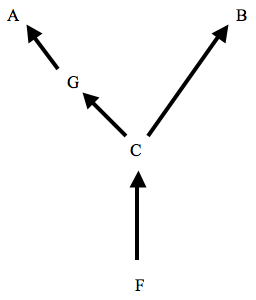

(i) The CCP does not say that all common causes satisfy condition 2–6, nor that anything satisfying 2–6 is a common cause. In fact, both of these are false. For example, in the structure depicted in Figure 7, F is a common cause of A and B, but will not screen A off from B; G will satisfy conditions 2–6, but is not a cause of B and hence not a common cause of A and B.

Figure 7

(ii) The CCP is a principle concerning correlations in the probabilistic sense of 1. Other things that we might informally call correlations do not fall within the scope of CCP. For example, the bone structures of human hands, bat wings, and whale fins are remarkably similar. From this, we infer that humans, bats, and whales share a common ancestor. But this is not an application of CCP, for the similarity of bone structure is not a correlation in the probabilitistic sense.

(iii) The derivation of 1 from conditions 3–6 is invalid if condition 2 is not met. In particular, if P(C) = 1, then condition 3 entails that P(A & B) = P(A)P(B), contrary to 1. A common cause only gives rise to a correlation by having some probability of occurring, and some probability of failing to occur. Thus, for example, Salmon (1984) is mistaken in reconstructing Perrin's argument for the existence of atoms as a common cause argument. Since atoms are always present, they cannot give rise to a correlation in the probabilistic sense.

(iv) Although Reichenbach is not always clear about this, CCP does not tell us that if particular events A and B both occur, then we should infer that some particular event C, which causes both A and B, also occurs. It follows from conditions 2–6 that if A and B have both occurred, it is more likely that C has occurred than if either A or B had failed to occur; i.e. P(C | A & B) > P(C |~(A & B)). But any common cause model, that is, any set of probability values satisfying 2–6, will typically entail some positive probability for ~C even if A and B occur (the only exception is when either P(A | ~C) or P(B | ~C) is zero); moreover, 2 – 6 by themselves impose no upper bound on the probability P(~C | A & B).