Supplement to Hermann Weyl

Weyl’s metric-independent construction of the symmetric linear connection

Weyl characterizes the notion of a symmetric linear connection as follows:

Definition A.1 (Affine Connection)

Let T(Mp) denote the tangent space of M at p∈M. A

point p∈M is affinely connected with its immediate

neighborhood, if and only if for every vector vp∈T(Mp),

a vector at q

is determined to which the vector vp∈T(Mp) gives rise under parallel displacement from p to the infinitesimally neighboring point q.

Of the notion of parallel displacement, Weyl requires that it satisfy the following condition.

Definition A.2 (Parallel Displacement)

The transport of a vector vp∈T(Mp) to an infinitesimally

neighboring point q∈M constitutes a parallel displacement if

and only if there exists a coordinate system ¯xi

(called a geodesic coordinate system) for the neighborhood of

p∈M, relative to which the transported vector

¯vq possesses the same components as

¯vp; that is,

The requirement that there exist a geodesic coordinate system such that (45) is satisfied, characterizes the essential nature of parallel transport.

It is natural to require that for an arbitrary coordinate system the components dvip in (44) vanish whenever vip or dxip vanish. Hence, the simplest assumption that can be made about the components dvip is that they are linearly dependent on the two vectors vip and dxip. That is, dvip must be bilinear in vip and in dxip; that is,

dvip=−Γijk(x)vjpdxkp,where the n3 coefficients Γijk(x) are coordinate functions, that is functions of xi (i=1,…,n), and the minus sign is introduced to agree with convention.

The vjp and dxkp in (46) are vectors, but dvip=viq−vip is not a vector since the vectors viq and vip lie in different tangent planes and cannot be subtracted. Hence the coefficients Γijk(x) do not constitute a tensor; they conform to a linear but non-homogeneous transformation law. The vector

viq=vip+dvip=vip−Γijkvjpdxkpis called the parallel displaced vector.

Weyl (1918b, 1923b) proves the following theorem.

Theorem A.3

If for every point p in a neighborhood U of M, there

exists a geodesic coordinate system ¯x such that the

change in the components of a vector under parallel transport to an

infinitesimally near point q is given by

then locally in any other coordinate system x,

dvip=−Γijk(x)vjpdxkp,where Γijk(x)=Γikj(x), and conversely.

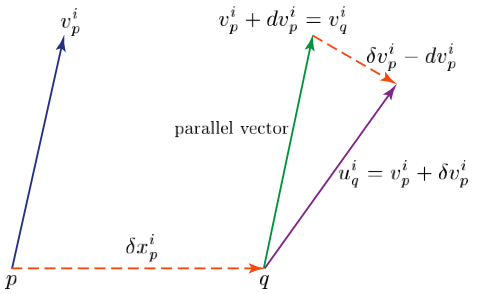

The idea of parallel displacement leads immediately to the idea of the covariant derivative of a vector field. Consider a vector field vi(x) evaluated at two nearby points p and q with arbitrary coordinates xi and xi+δxi respectively. A first-order Taylor expansion yields

uiq=vip(x+δx)=vip(x)+∂vi∂xjδxjp.If we set

∂vi∂xjδxjp=δvip(x),then

δvip(x)=vip(x+δx)−vip(x),and

uiq=vip+δvip.The array of derivatives

∂vi∂xjdo not constitute a tensorial entity, because the derivatives are formed by the inadmissible procedure of subtracting the vector vip(x) at p from the vector uiq=vip(x+δx) at q. Their difference δvip(x) is not a vector since the vectors lie in the different tangent spaces T(Mp) and T(Mq), respectively. Since δxip is a vector whereas δvip is not, the array of derivatives

∂vi∂xjin (50) cannot therefore be a tensorial entity. To form a derivative that is tensorial, that is covariant or invariant, we must subtract from the vector uiq=vip+δvip not the vector vip, but another vector at q which “represents” the original vector vip as “unchanged” as we proceed from p to q. Such a representative vector at q may be obtained by parallel transport of the vector vip to the nearby point q, and will be denoted, given an arbitrary coordinate system x, by

viq=vip+dvip.Since dvip is the difference between vip and viq, dvip is also not a vector for the for the reasons given above; however, the difference

uq−vq=vip+δvip−[vip+dvip]=δvip−dvipis a vector and is therefore a tensorial entity.

Figure 16: Covariant differentiation

The covariant derivative can now be defined by the limiting process

∇kvip=limIn general, one writes the covariant derivative of a vector field v^{i} simply as

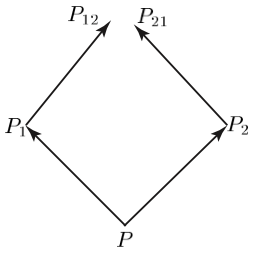

\tag{56} \nabla_{k}v^{\,i} = \partial_{k}v^{\,i} + \Gamma^{i}_{jk}v^{\,j}.Weyl (1918b, §3.I.B) also provided a more synthetic argument to establish the symmetry of the affine connection. He considers two infinitesimal vectors \overline{PP}_{1} and \overline{PP}_{2} at a point P. The vector \overline{PP}_{1} under parallel transport along \overline{PP}_{2} goes into \overline{P_{2}P}_{21}. Similarly, the vector \overline{PP}_{2} under parallel transport along \overline{PP}_{1} goes into \overline{P_{1}P}_{12}. These relationships are illustrated in figure 17.

Figure 17: Symmetry of Parallel Transport

The condition imposed on parallel transport is that the four vectors \overline{PP}_{1}, \overline{P_{1}P}_{12}, \overline{PP}_{2} and \overline{P_{2}P}_{21} form a closed parallelogram; that is, the points P_{12} and P_{21} coincide. It follows that

\tag{57} \overline{PP}_{1} + \overline{P_{1}P}_{12} = \overline{PP}_{2} + \overline{P_{2}P}_{21}.Denote the coordinates of \overline{PP}_{1} and \overline{PP}_{2} by dx^{i} and \delta x^{i}, respectively. The coordinates of \overline{P_{2}P}_{21} and \overline{P_{1}P}_{12} are respectively denoted by dx^{i} + \delta dx^{i} and \delta x^{i} + d\delta x^{i}. Substitution into (57) yields

\tag{58} dx^{i} + \delta x^{i} + d\delta x^{i} = \delta x^{i} + dx^{i} + \delta dx^{i},or

\tag{59} d\delta x^{i} = \delta dx^{i}.From the assumption that the vectors transform linearly, one has

\tag{60} \begin{matrix} \delta dx^{i} = - \delta \gamma^{i}_{r}dx^{r} & \text{and} & d\delta x^{i} = - d\gamma^{i}_{r}\delta x^{r} \end{matrix}From the assumption that the infinitesimal transformation coefficients \delta \gamma^{i}_{r} and d\gamma^{i}_{r} are of the same order as the corresponding differentials \delta x^{i} and dx^{i}, one obtains

\tag{61} \begin{matrix} \delta \gamma^{i}_{r} = \Gamma^{i}_{rs}\delta x^{s} & \text{and} & d\gamma^{i}_{r} = \Gamma^{i}_{rs}dx^{s}. \end{matrix}Substitution of (60) and (61) into (59) yields

\tag{62} \Gamma^{i}_{jk} = \Gamma^{i}_{kj}