| This is a file in the archives of the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. |

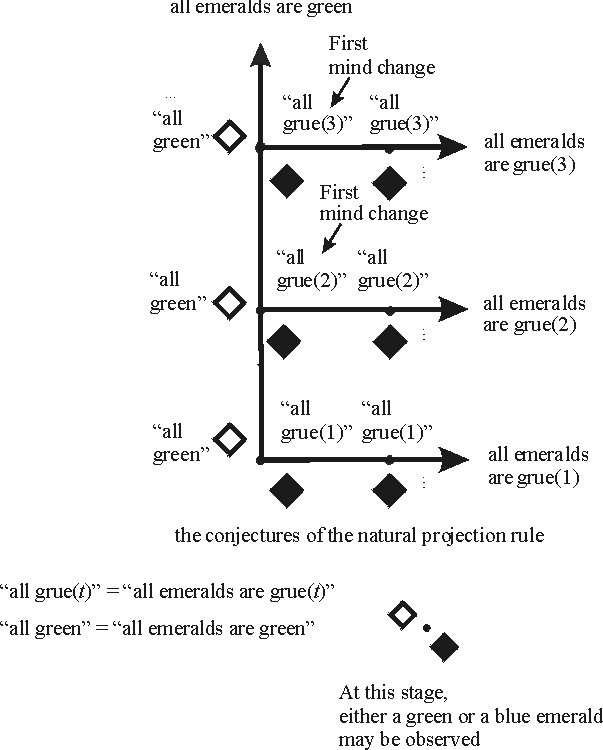

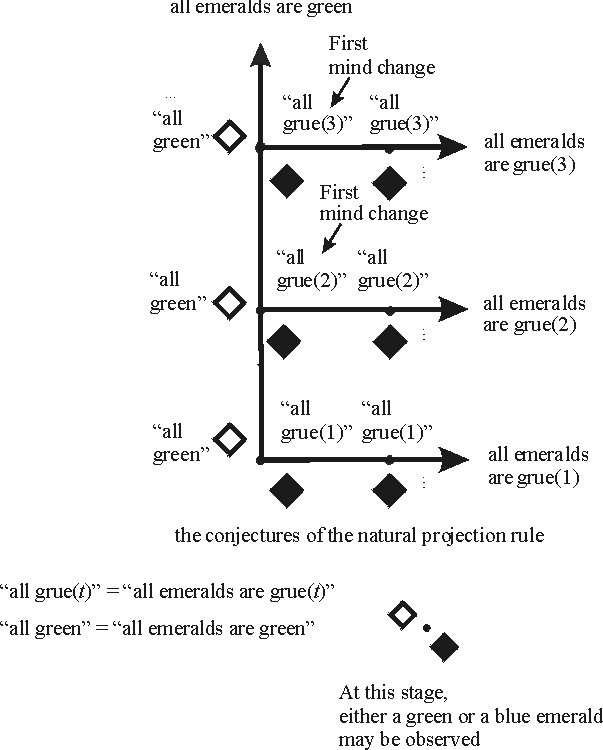

The basic building block of formal learning theory is the notion of an evidence item. For a general formulation, we may simply begin with a set E of evidence items. In general, nothing need be assumed about this set; in what follows, I will assume that E is at most countable, that is, that there are at most countably many evidence items. Some authors assume that evidence is formulated in first-order logic, typically as literals (e.g., [Earman 1992], [Martin and Osherson 1988]). In formal models of language learning, the evidence items are strings, representing grammatical strings from the language to be learned. In the example of the Riddle of Induction, the evidence items are G and B, respectively represented in the picture by a transparent and by a filled diamond, so E = {G,B}.

Given the basic set E of evidence items, we have the notion of a finite evidence sequence. A finite evidence sequence is a sequence (e1, e2, ..., en) of evidence items, that is, members of E. For example, the observation that the first three emeralds are green corresponds to the evidence sequence (G,G,G). A typical notation for a finite evidence sequence is e. If a finite evidence sequence e has n members, we say that the sequence is of length n and write lh(e) = n.

The next step is to consider an infinite evidence

sequence. An infinite evidence sequence is a sequence

(e1, e2, ..., en, ...) that

continues indefinitely. For example, the infinite sequence

(G,G,G,...,G,....) represents the circumstance in which all observed

emeralds are green. A typical notation for an infinite evidence

sequence is

![]() .

Following Kelly [1996], the remainder of this supplement refers to

an infinite evidence sequence as a data stream. Even though

the notion of an infinite data sequence is mathematically

straightforward, it takes some practice to get used to employing

it. We often have occasion to refer to finite initial segments of a

data stream, and introduce some special notation for this purpose:

Let

.

Following Kelly [1996], the remainder of this supplement refers to

an infinite evidence sequence as a data stream. Even though

the notion of an infinite data sequence is mathematically

straightforward, it takes some practice to get used to employing

it. We often have occasion to refer to finite initial segments of a

data stream, and introduce some special notation for this purpose:

Let

![]() |n

denote the first n evidence items in the data stream

|n

denote the first n evidence items in the data stream

![]() .

For example if

.

For example if

![]() = (G,G,G,...,G,...) is the data stream featuring only green emeralds, then

= (G,G,G,...,G,...) is the data stream featuring only green emeralds, then

![]() |3

= (G,G,G) is the finite evidence sequence corresponding to the

observation that the first three emeralds are green. We also write

|3

= (G,G,G) is the finite evidence sequence corresponding to the

observation that the first three emeralds are green. We also write

![]() n

to denote the n-th evidence item observed in

n

to denote the n-th evidence item observed in

![]() .

For example, if

.

For example, if

![]() = (G,G,G,...,G,...), then

= (G,G,G,...,G,...), then

![]() 2 = G.

2 = G.

An empirical hypothesis is a claim whose truth supervenes on

a data stream. That is, a complete infinite sequence of observations

settles whether or not an empirical hypothesis is true. For example,

the hypothesis that "all observed emeralds are green" is

true on the data stream featuring only green emeralds, and false on

any data stream featuring a nongreen emerald. In general, we assume

that a correctness relation C has been specified, where

C(![]() ,H)

holds just in case hypothesis H is correct an data stream

,H)

holds just in case hypothesis H is correct an data stream

![]() .

What hypotheses are taken as correct on which data streams is a

matter of the particular application. Given a correctness relation,

we can define the empirical content of a hypothesis H as the

set of data streams on which H is correct. Thus the empirical

content of hypothesis H is given by

{

.

What hypotheses are taken as correct on which data streams is a

matter of the particular application. Given a correctness relation,

we can define the empirical content of a hypothesis H as the

set of data streams on which H is correct. Thus the empirical

content of hypothesis H is given by

{![]() :

C(

:

C(![]() ,

H)}. For formal purposes, it is often easiest to dispense

with the correctness relation and simply to identify hypotheses with

their empirical content. With that understanding, in what follows

hypotheses will often be viewed as sets of data streams. For

ease of exposition, I do not always distinguish between a hypothesis

viewed as a set of data streams and an expression denoting that

hypothesis, such as "all emeralds are green".

,

H)}. For formal purposes, it is often easiest to dispense

with the correctness relation and simply to identify hypotheses with

their empirical content. With that understanding, in what follows

hypotheses will often be viewed as sets of data streams. For

ease of exposition, I do not always distinguish between a hypothesis

viewed as a set of data streams and an expression denoting that

hypothesis, such as "all emeralds are green".

An inquirer typically does not begin inquiry as a tabula rasa, but has background assumptions about what the world is like. To the extent that such background assumptions help in inductive inquiry, they restrict the space of possible observations. For example in the discussion of the Riddle of Induction above, I assumed that that no data stream will be obtained that has green emeralds followed by blue emeralds followed by green emeralds. In the conservation principle problem discussed in the main entry, the operative background assumption is that the complete particle dynamics can be accounted for with conservation principles. As with hypotheses, we can represent the empirical content of given background assumptions by a set of data streams. Again it is simplest to identify background knowledge K with a set of data streams, namely the ones consistent with the background knowledge.

In a logical setting in which evidence statements are literals,

learning theorists typically assume that a given data stream will

feature all literals of the given first-order language (statements

such as P(a) or

![]() P(a)),

and that the total set of evidence statements obtained during

inquiry is consistent. With that background assumption, we may view

the formula

P(a)),

and that the total set of evidence statements obtained during

inquiry is consistent. With that background assumption, we may view

the formula

![]() x.P(x)

as an empirical hypothesis that is correct on an infinite evidence

sequence

x.P(x)

as an empirical hypothesis that is correct on an infinite evidence

sequence

![]() just in case no literal

just in case no literal

![]() P(a)

appears on

P(a)

appears on

![]() ,

that is for all n it is the case that

,

that is for all n it is the case that

![]() n

n

![]()

![]() P(a).

More generally, a data stream with a complete, consistent

enumeration of literals determines the truth of every quantified

statement in the given first-order language.

P(a).

More generally, a data stream with a complete, consistent

enumeration of literals determines the truth of every quantified

statement in the given first-order language.

An inductive method is a function that assigns hypotheses to

finite evidence sequences. Following Kelly [1996], I use the symbol

![]() for an inductive method. Thus if e is a finite evidence

sequence, then

for an inductive method. Thus if e is a finite evidence

sequence, then

![]() (e)

= H expresses the fact that on finite evidence sequence

e, the method

(e)

= H expresses the fact that on finite evidence sequence

e, the method

![]() outputs hypothesis H. It is also possible to have a method

outputs hypothesis H. It is also possible to have a method

![]() assign probabilities to hypotheses rather than choose a single

conjecture, but I leave this complication aside here. Inductive

methods are also called "learners" or

"scientists"; no matter what the label is, the mathematical

concept is the same. In the Goodmanian Riddle above, the natural

projection rule outputs the hypothesis "all emeralds are

green" on any finite sequence of green emeralds. Thus if we

denote the natural projection rule by

assign probabilities to hypotheses rather than choose a single

conjecture, but I leave this complication aside here. Inductive

methods are also called "learners" or

"scientists"; no matter what the label is, the mathematical

concept is the same. In the Goodmanian Riddle above, the natural

projection rule outputs the hypothesis "all emeralds are

green" on any finite sequence of green emeralds. Thus if we

denote the natural projection rule by

![]() ,

and the hypothesis that all emeralds are green by "all G",

we have that

,

and the hypothesis that all emeralds are green by "all G",

we have that

![]() (G)

= "all G",

(G)

= "all G",

![]() (GG)

= "all G", and so forth. Letting

(GG)

= "all G", and so forth. Letting

![]() = (G,G,G,...,G,...) be the data stream with all green emeralds, we

can write

= (G,G,G,...,G,...) be the data stream with all green emeralds, we

can write

![]() |1

= (G),

|1

= (G),

![]() |2

= (GG), etc., so we have that

|2

= (GG), etc., so we have that

![]() (

(![]() |1)

= "all G",

|1)

= "all G",

![]() (

(![]() |2)

= "all G", and more generally that

|2)

= "all G", and more generally that

![]() (

(![]() |n)

= "all G" for all n.

|n)

= "all G" for all n.

An inductive method

![]() converges to a hypothesis H on a data stream

converges to a hypothesis H on a data stream

![]() by time n just in case for all later times

n'

by time n just in case for all later times

n'![]() n, we have that

n, we have that

![]() (

(![]() |n')

= H. This is a central definition for defining empirical

success, as we will see shortly. To illustrate, the natural

projection rule converges to "all G" by time 1 on the data

stream

|n')

= H. This is a central definition for defining empirical

success, as we will see shortly. To illustrate, the natural

projection rule converges to "all G" by time 1 on the data

stream

![]() = (G,G,G,...,G,...). It converges to "all emeralds are

grue(3)" by time 3 on the data stream (G,G,B,B,B, ...). An

inductive method

= (G,G,G,...,G,...). It converges to "all emeralds are

grue(3)" by time 3 on the data stream (G,G,B,B,B, ...). An

inductive method

![]() converges to a hypothesis H on a data stream

converges to a hypothesis H on a data stream

![]() just in case there is a time n such that

just in case there is a time n such that

![]() converges to H on

converges to H on

![]() by time n. Thus on the data stream (G,G,G...), the natural projection

by time n. Thus on the data stream (G,G,G...), the natural projection

![]() converges to "all G" whereas on the data stream

(G,G,B,B,...) this rule converges to "all emeralds are

grue(3)".

converges to "all G" whereas on the data stream

(G,G,B,B,...) this rule converges to "all emeralds are

grue(3)".

A discovery problem is a pair (H, K) where K

is a set of data streams representing background knowledge and

H is a mutually exclusive set of hypotheses that covers

K. That is, for any two hypotheses H, H' in

H, viewed as two sets of data streams, we have that H

![]() H' =

H' =

![]() .

And for any data stream

.

And for any data stream

![]() in K, there is a (unique) hypothesis H in H such that

in K, there is a (unique) hypothesis H in H such that

![]()

![]() H. For example, in the Goodmanian Riddle of Induction, each

alternative hypothesis is a singleton containing just one data

stream, for example {(G,G,G,...)} for the empirical content of

"all emeralds are green". The background knowledge K

is just the union of the alternative hypotheses. In the problem

involving the generalizations "all but finitely many ravens are

white" and "all but finitely many ravens are black",

the former hypothesis corresponds to the set of data streams

featuring only finitely many black ravens, and the latter to the set

of data streams featuring only finitely many white ravens. The

background knowledge K corresponds to the set of data streams

that eventually feature only white ravens or eventually feature only

black ravens. Since each alternative hypothesis in a discovery

problem (H, K) is mutually exclusive, for a given data

stream

H. For example, in the Goodmanian Riddle of Induction, each

alternative hypothesis is a singleton containing just one data

stream, for example {(G,G,G,...)} for the empirical content of

"all emeralds are green". The background knowledge K

is just the union of the alternative hypotheses. In the problem

involving the generalizations "all but finitely many ravens are

white" and "all but finitely many ravens are black",

the former hypothesis corresponds to the set of data streams

featuring only finitely many black ravens, and the latter to the set

of data streams featuring only finitely many white ravens. The

background knowledge K corresponds to the set of data streams

that eventually feature only white ravens or eventually feature only

black ravens. Since each alternative hypothesis in a discovery

problem (H, K) is mutually exclusive, for a given data

stream

![]() in K there is exactly one hypothesis correct for that data

stream; I write

H(

in K there is exactly one hypothesis correct for that data

stream; I write

H(![]() )

to denote that hypothesis.

)

to denote that hypothesis.

In a discovery problem (H, K), an inductive method

![]() succeeds on a data stream

succeeds on a data stream

![]() in K iff

in K iff

![]() converges to the hypothesis correct for

converges to the hypothesis correct for

![]() ;

more formally,

;

more formally,

![]() succeeds on a data stream

succeeds on a data stream

![]() in K iff

in K iff

![]() converges to

H(

converges to

H(![]() ) on

) on

![]() .

An inductive method

.

An inductive method

![]() solves the discovery problem (H, K) iff

solves the discovery problem (H, K) iff

![]() succeeds on all data streams in K. If

succeeds on all data streams in K. If

![]() solves a discovery problem (H, K), then we also say that

solves a discovery problem (H, K), then we also say that

![]() is reliable for (H, K). If there is a reliable

inductive method

is reliable for (H, K). If there is a reliable

inductive method

![]() for a discovery problem (H, K), we say that the

problem (H, K) is solvable. The main entry

presented several solvable discovery problems. Characterization

theorems like the one discussed there give conditions under which a

discovery problem is solvable.

for a discovery problem (H, K), we say that the

problem (H, K) is solvable. The main entry

presented several solvable discovery problems. Characterization

theorems like the one discussed there give conditions under which a

discovery problem is solvable.

Efficient inductive inquiry is concerned with maximizing

epistemic values other than convergence to the truth. Minimizing the

number of mind changes is a topic in the main entry; what follows

defines this measure of inductive performance as well as error and

convergence time. Consider a discovery problem (H, K)

and a data stream

![]() in K.

in K.

As we saw in the main entry, assessing methods by how well they do vis-a-vis these criteria of cognitive success leads to restrictions on inductive inferences in the short run, sometimes very strong restrictions. Learning-theoretic characterization theorems specify the structure of problems in which efficient inquiry is possible, and what kind of inferences lead to inductive success when it is attainable.

Return to Formal Learning Theory

First published: February 2, 2002

Content last modified: February 2, 2002