Social Epistemology

Until recently, epistemology—the study of knowledge and justified belief—was heavily individualistic in focus. The emphasis was on evaluating doxastic attitudes (beliefs and disbeliefs) of individuals in abstraction from their social environment. Social epistemology seeks to redress this imbalance by investigating the epistemic effects of social interactions and social systems. After giving an introduction, and reviewing the history of the field in sections 1 and 3, we move on to discuss central topics in social epistemology in section 3. These include testimony, peer disagreement, and judgment aggregation, among others. Section 4 turns to recent approaches which have used formal methods to address core topics in social epistemology, as well as wider questions about the functioning of epistemic communities like those in science. In section 5 we briefly turn to questions related to social epistemology and the proper functioning of democratic societies.

- 1. What is Social Epistemology?

- 2. Giving Shape to the Field of Social Epistemology

- 3. Central Topics in Social Epistemology

- 4. Formal Approaches to Social Epistemology

- 4.2 The Credit Economy

- 4.3 Network Epistemology Models

- 5. Social Epistemology and Society

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. What is Social Epistemology?

What do we mean by the phrase “social epistemology”, the topic covered in this entry?

Social epistemology gets its distinctive character by standing in contrast with what might be dubbed “individual” epistemology. Epistemology in general is concerned with how people should go about the business of trying to determine what is true, or what are the facts of the matter, on selected topics. In the case of individual epistemology, the person or agent in question who seeks the truth is a single individual who undertakes the task all by himself/herself, without consulting others. By contrast social epistemology is, in the first instance, an enterprise concerned with how people can best pursue the truth (whichever truth is in question) with the help of, or in the face of, others. It is also concerned with truth acquisition by groups, or collective agents.

According to the most influential tradition in (Western) epistemology, illustrated vividly by René Descartes (1637), standard epistemology has taken the form of individual epistemology, in which the object of study is how epistemic agents, using their personal cognitive devices, can soundly investigate assorted questions. Descartes contended that the most promising way to pursue truth is by one’s own reasoning. The remaining question was how, exactly, truth was to be found by suitable individualistic maneuvers, starting from one’s own introspected mental contents. Another major figure in the history of the field was John Locke (1690), who insisted that knowledge be acquired through intellectual self-reliance. As he put it, “other men’s opinions floating in one’s brain” do not constitute genuine knowledge.

In contrast with the individualistic orientations of Descartes and Locke, social epistemology proceeds on the commonsensical idea that information can often be acquired from others. To be sure, this step cannot be taken unless the primary investigator has already determined that there are such people, a determination that presumably requires the use of individual resources (hearing, seeing, language, etc.) Social epistemology should thus not be understood as a wholly distinct and independent form of epistemology, but one that rests on individual epistemology.

Surprisingly, social epistemology does not have a very long, or rich, history. With perhaps a few exceptions, it has not been explored by philosophy with much systematicity until recent times. The case of modern science, by contrast, was rather different. Under the leadership of Francis Bacon, the Royal Society of London was created in 1660, intended to highlight the importance of multiple observers in establishing recognized facts. (And, as we will see throughout the entry, there are important connections between philosophy of science and social epistemology.) But the leading figures of philosophy commonly tended to present themselves as solitary investigators. To be sure, they did not refrain from debating with one another. But insofar as the topic was “epistemology” (as it came to be called), it centered on the challenges and practices of individual agents.

2. Giving Shape to the Field of Social Epistemology

A movement somewhat analogous to social epistemology was developed in the middle part of the 20th century, in which sociologists and deconstructionists set out to debunk orthodox epistemology, sometimes challenging the very possibility of truth, rationality, factuality, and/or other presumed desiderata of mainstream epistemology. Members of the “strong program” in the sociology of science, such as Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar (1986), challenged the notions of objective truth and factuality, arguing that so-called “facts” are not discovered or revealed by science, but instead “constructed”, “constituted”, or “fabricated”. “There is no object beyond discourse,” they wrote. “The organization of discourse is the object” (1986: 73).

A similar version of postmodernism was offered by the philosopher Richard Rorty (1979). Rorty rejected the traditional conception of knowledge as “accuracy of representation” and sought to replace it with a notion of “social justification of belief”. As he expressed it, there is no such thing as a classical “objective truth”. The closest thing to (so called) truth is merely the practice of “keeping the conversation going” (1979: 377).

Other forms of deconstruction were also inspired by social factors but were less extreme in embracing anti-objectivist conclusions about science. Thomas Kuhn (1962/1970) held that purely objective considerations could never settle disputes between competing theories; hence scientific beliefs must be influenced by social factors. Analogously, Michel Foucault developed a radically political view of knowledge and science, arguing that practices of so-called knowledge-seeking are driven by quests for power and social domination (1969 [1972], 1975 [1977]).

Debates about these topics persisted under the heading of “the science wars”. Within the mainstreams of both science and philosophy, however, the foregoing views have generally been rejected as implausibly radical. This did not mean that no lessons were learned about the status of social factors in science and philosophy. These debates gave important insight into the role of cultural beliefs and biases in the creation of knowledge. What we shall pursue, however, in the remainder of this entry is how social epistemology has created a new branch, or sphere, of mainstream epistemology. According to this “extension” of epistemology, social factors can and do make major contributions to traditional, truth-oriented epistemology by introducing, broadening, and refining new problems, new techniques, and new methodologies. But such factors do not undercut the very notions of truth and falsity, knowledge and error.

Sharply departing from the debunking themes sketched above, modern social epistemology is prepared to advance proposals quite continuous with traditional epistemology. It sees no reason to think that social factors or practices inevitably interfere with, or pose threats to, the attainment of truth and/or other epistemic desiderata, such as justified belief, rational belief, etc. There may indeed be identifiable cases (which we shall explore) in which specific types of social factors or social interactions pose threats to truth acquisition. But, conversely, the right kinds of social organization may enhance the prospects of truth acquisition.

A general overview of these different kinds of cases was advanced in a wide-ranging monograph by Alvin Goldman: Knowledge in a Social World (1999). This book emerged from several earlier papers critiquing postmodernist attacks on truth and the prospects of truth acquisition. They included papers on argumentation (Goldman 1994), freedom of speech (Goldman and Cox 1996), and scientific inquiry (Goldman 1987). Other contributions with broadly similar orientations included C.A.J. Coady’s Testimony (1992), Edward Craig’s Knowledge and the State of Nature (1990), and Philip Kitcher’s “The Division of Cognitive Labor” (1990) and The Advancement of Science (1993). Margaret Gilbert’s monograph On Social Facts (1989) made a forceful case for the existence of “plural subjects”, a crucial metaphysical component for social epistemology. The journal Episteme: A Journal of Social Epistemology (Goldman, editor), was begun in 2004 and played a major role in the positive development of the field. (A different journal with a similar title, Social Epistemology (Steve Fuller, editor) began somewhat earlier in 1988, but tilted heavily toward a debunking orientation).

3. Central Topics in Social Epistemology

In exploring social epistemology we explore how assorted social-epistemic activities or practices have an impact on the epistemic outcomes of the agents (or groups) in question. Which changes in social-epistemic practices are likely to promote, enhance, or impede epistemic outcomes? To put more flesh on the varieties of social-epistemic methods and outcomes, let us look at some core topics.

3.1 Testimony

The first kind of social-epistemic scenario is very common. An individual seeks to determine the truth-value of proposition p by soliciting the opinion(s) of others. She might direct her question to one of her personal confidants, or consult what is in print or available online. Having received responses to her queries, she weighs what has been said to help her assess the truth of the proposition in question. This is commonly referred to as “testimony-based” belief. The selected informant may still be a single individual. But appealing to another individual for testimony already locates the example as within the domain of social epistemology.

The main discussion here is framed in terms of justification rather than knowledge. The standard question is: Under what circumstances is a hearer justified in trusting an assertion made by a stranger, or by a consultant or speaker of any variety? David Hume argued that we are generally entitled to trust what others tell us; but this entitlement only arises by virtue of what we previously learned from others. Each of us can recall occasions on which we were told things that we could not independently verify (from perception, e.g.) but later determined to be true. This reliable track-record from the past (which we remember) warrants us in inferring (via induction) that testimony is generally reliable. As James Van Cleve formulates the view:

Testimony gives us justified belief … not because it shines by its own light, but because it has often enough been revealed true by our other lights. (Van Cleve 2006: 69)

This sort of view is called “reductionism” (about testimony) because it “reduces” the justification-conferring force of testimony to the combined forces of perception, memory, and inductive inference. More precisely, the view is usually called global reductionism, because it argues that hearers of testimony are justified in believing particular instances of testimony by inferential appeal to testimony’s general reliability.

However, global reductionism has come under fire. C.A.J. Coady argues that the observational basis of ordinary epistemic agents is much too thin and limited to allow an induction to the general reliability of testimony. He writes:[It] seems absurd to suggest that, individually, we have done anything like the amount of field-work that [reductionism] requires … [M]any of us have never seen a baby born, nor have many of us examined the circulation of the blood nor the actual geography of the world … nor a vast number of other observations that [reductionism] would seem to require. (Coady 1992: 82)

An alternative to global reductionism is local reductionism (E. Fricker 1994). Local reductionism does not require hearers to be justified in believing the general reliability of testimony. It only requires hearers to be justified in trusting the reliability of the specific speakers whose current testimony is in question on a particular subject. This requirement is more easily satisfied than global reductionism. Local reductionism may still be too strong, however, but for a different reason. Is a speaker S trustworthy for hearer H only if H has positive evidence or justification for S’s general reliability? This is far from clear. If I am at an airport or train station and hear a public announcement of the departure gate (or track), am I justified in believing this testimony only if I have prior evidence of the announcer’s general reliability? Normally I do not possess such evidence for a given public address announcer. But, surely, I am justified in trusting such announcements.

Given these problems for both kinds of reductionism, some epistemologists embrace testimonial anti-reductionism (Coady 1992; Burge 1993; Foley 1994; Lackey 2008). Anti-reductionism holds that testimony is itself a basic source of evidence or justifiedness. No matter how little positive evidence a hearer has about the reliability and sincerity of a given speaker, or of speakers in general, she has default or prima facie warrant in believing what the speaker says. Thus Tyler Burge writes:

[A] person is entitled to accept as true something that is presented as true and that is intelligible to him, unless there are stronger reasons not to do so. (Burge 1993: 457)

3.2 Peer Disagreement

In the preceding example, it was tacitly assumed that the hearer had no prior belief (one way or the other) about the topic in question. His/her mind was completely open prior to receiving the testimony of the speaker. Now let us consider a different class of examples (modified from one given by David Christensen [2007]). Suppose that two people start out with opposing views on a given topic; one of them believes proposition p and the other believes not-p. To add a little color, consider an example in which two friends, Harry and Mary, have each acquired some evidence about a traffic accident described in the morning newspaper. Neither has any other evidence about the incident. For example, neither has any background knowledge or information about the people said to be involved in the incident. However, having read the newspaper account, both Harry and Mary form beliefs about it. Harry believes that Jones (described in the newspaper) was responsible for the accident. Mary believes that Jones was not responsible. Harry and Mary now run into each other, find out that their friend has read the same story, and discuss their views about the accident. To make the example even more interesting, suppose the two friends have as much respect for the other person’s judgment (in such matters) as they do for themselves. This might be based on the fact that when they have disagreed with one another in the past, each turned out to be right about 50% of the time.

In such a situation, we shall call the two people epistemic peers. Epistemologists have adopted the label “peer disagreement” for the problem generated by such cases (actual or hypothetical). The problem is: how, if at all, should an agent adjust her initial belief about the specified proposition upon learning that her peer holds a contrary position? Should she (always?) modify her belief (or strength of belief) in the direction of the peer? Or is it sometimes epistemically permissible to hold “steadfast” to one’s own original conviction?

“Conciliationism” is the view that (some degree of) modification is always called for, because it requires epistemic agents in the specified type of situation to make some obeisance to the belief of their peer, rather than ignoring or dismissing it entirely. Proponents of conciliationism include Christensen (2007), Richard Feldman (2007), and Adam Elga (2007).

Feldman (2007) offers an abstract argument for conciliationism based on what he calls the “uniqueness thesis”. This is the view that for any proposition p and any body of evidence E, exactly one doxastic attitude is the rational attitude to have toward p, where the possible attitudes include believing p, disbelieving p, and suspending judgment. Feldman’s argument seems to be that if the uniqueness theory is true, then when I believe p and my peer believes not-p, at least one of us must have formed an irrational opinion. Since I have no good reason to believe that I am not the misguided believer, the only rational option is to suspend judgment. But few people accept the uniqueness thesis. Are epistemic rules or principles really (always) so precise and restrictive?

Critics of conciliationism offer a number of reasons for rejecting it as a systematic epistemic requirement. One line of criticism runs as follows. Conciliationism may well be self-refuting. Since the truth of conciliationism is itself a matter of controversy, a proponent of conciliationism should become much less convinced of its truth when he learns about this controversy. One may worry that there is something wrong with a principle that tells you not to believe in its own truth. (For further discussion, see Christensen 2013.)

Thomas Kelly (2010) offers a different reason for rejecting conciliationism, or at least for denying its ubiquitous appropriateness. He argues as follows:

[If] you and I have arrived at our opinions in response to a substantial body of evidence, and your opinion is a reasonable response to the evidence while mine is not, then you are not required to give equal weight to my opinion and to your own. Indeed, one might wonder whether you are required to give any weight to my opinion in such circumstances. (2010: 135)

He acknowledges that whether one reasons well or badly, one might be equally confident in one’s conclusion in both cases. However, he contends, “We should not thereby be drawn to the conclusion that the deliverances of good reasoning and bad reasoning have the same epistemic status” (2010: 141). Rather, the person that reasons better (from the same evidence) may well be more entitled to his/her conclusion than the person who reasons worse. It may be rational for her to hold fast to her initial belief. This approach is what Kelly calls the “Total Evidence View”.

3.3 The Epistemology of Collective Agents

The cases discussed thus far focus on epistemic agents who are individuals. We subsumed these cases under the heading of social epistemology not because the believers themselves have some sort of social character, but because there are players who rely upon, or appeal to, other epistemic agents. However, there are other types of cases that are naturally treated as social epistemology for an entirely different reason.

It is common to ascribe actions, intentions, and representational states—including belief states—to collections or groups of people. Such collections would include juries, panels, governments, assemblies, teams, etc. The State of California might be said to know that chemical XYZ is a cause of cancer. What does it take for a group to believe something? Some take what is called the “summative approach”—a group believes something just in case all, or almost all, of its members hold the belief (see, for instance, Quinton 1976: 17). Margaret Gilbert, however, has pointed out that in ordinary language use it is common to ascribe a belief to a group without assuming that all members hold the belief in question. In seeking to address why this usage is acceptable, she advances a “collective” account of group belief. Under this view:

A group G believes that p if and only if the members of G are jointly committed to believe that p as a body.

Joint commitments create normative requirements for group members to emulate a single believer of p. On Gilbert’s account, the commitment to act this way is common knowledge, and if group members do not act accordingly they can be held normatively responsible by their peers for failing to do so (see Gilbert 1987, 1989, 2004). Frederick Schmitt (1994a), similarly offers a collective, commitment-based account of group belief.

Some have argued that these views are not properly about group belief because they focus on responsibility to peers, and not on the beliefs-states of the group members. Wray (2001) suggests that these should be considered accounts of group acceptance instead. Later in the entry, we will address some accounts that take individual beliefs as inputs and output some group belief. It will become clear how different these are from a joint commitment type view.

A different approach is taken by Alexander Bird (2014) who contends that the acceptance model of group belief is only one of many different (but legitimate) models. For instance, he introduces the “distributed model” to deal with systems that feature information-intensive tasks which cannot be processed by a single individual. Several individuals must gather different pieces of information while others coordinate this information and use it to complete the task. A famous example is provided by Edwin Hutchins (1995) who describes a large ship where different crew members take different bearings so that a plotter can determine the ship’s position and course. Members in such a distributed system will not ordinarily satisfy the conditions of mutual awareness and commitment that Gilbert and Schmitt require. Nonetheless, this seems to be a perfectly plausible species of group belief. Indeed, Bird contends that this is a fairly standard type of group model that occurs in science. Notice that for this model, again, it is quite possible that not all members of the group hold the same belief.

3.4. Judgment Aggregation

What about other attempts to provide an account of group belief? Christian List and Philip Pettit (2011) explore how individuals may yield a group belief through “judgment aggregation”. Although List and Pettit do not put it this way, it seems that aggregation refers to metaphysical relations between beliefs of group members and beliefs of the groups they compose. It refers to ways in which a set of beliefs by group members can give rise to beliefs held by the group. Here is how List and Pettit express these metaphysical relations:

The things a group agent does are clearly determined by the things its members do: they cannot emerge independently. In particular, no group agent can form propositional attitudes without the latter attitudes’ being determined, in one way or another, by certain contributions of its members, and no group agent can act without one or more of its members acting. (2011: 64)

The foregoing passage places some limits on the metaphysical relations between member attitudes and group attitudes. It tells us something about when group propositional attitudes occur, without implying anything about when the latter attitudes are justified. But social epistemologists are interested in the relation between the epistemic statuses of members’ beliefs and the epistemic status of group beliefs. List and Pettit address (something like) this question by exploring the sorts of judgment “functions”, i.e., rules for aggregation, that might come into play.

A sticky problem that emerges here is the “doctrinal paradox,” originally formulated by Kornhauser and Sager (1986) in the context of legal judgments. Suppose that a court consisting of three judges must render a judgment in a breach-of-contract case. The group judgment is to be based on each of three related propositions, where the first two propositions are premises and the third proposition is the conclusion. For example:

- The defendant was legally obliged not to do a certain action.

- The defendant did do that action.

- The defendant is liable for breach of contract.

Legal doctrine entails that obligation and action are jointly necessary and sufficient for liability. That is, conclusion (3) is true if and only if the two preceding premises, (1) and (2), are each true. Suppose, however, as shown in the table below, that the three judges form the indicated beliefs, vote accordingly, and the judgment-aggregation function delivers a conclusion guided by majority rule. In this case, the court as a whole forms beliefs and casts votes as shown below:

| Obligation? | Action? | Liable? | |

| Judge 1 | True | True | True |

| Judge 2 | True | False | False |

| Judge 3 | False | True | False |

| Group | True | True | False |

In this example, each of the three judges has a logically self-consistent set of beliefs. Moreover, a majority aggregation function seems eminently reasonable. Nonetheless, the upshot is that the court’s judgments are jointly inconsistent.

This kind of problem arises easily when a judgment is made by multiple members of a collective entity. This led List and Pettit to prove an impossibility theorem in which a reasonable-looking combination of constraints is nonetheless shown to be jointly unsatisfiable in judgment aggregation (List and Pettit 2011: 50). They begin by introducing four conditions that seem to be ones that a reasonable aggregation function should satisfy:

Universal domain: The aggregation function admits as input any possible profile of individual attitudes toward the propositions on the agenda, assuming that individual attitudes are consistent and complete.

Collective rationality: The aggregation function produces as output consistent and complete group attitudes toward the propositions on the agenda.

Anonymity: All individuals’ attitudes are given equal weight in determining the group attitude.

Systematicity: The group attitude on each proposition depends on the individuals’ attitudes toward it, not on their attitudes toward other propositions, and the pattern of dependence between individual and collective attitudes is the same for all propositions.

Although these four conditions seem initially plausible, they cannot be jointly satisfied. Having proved this List and Pettit proceed to explore “escape routes” from this impossibility. They offer ways to relax the requirements so that majority voting, for example, does satisfy the collective rationality desideratum.

Briggs et al. (2014) offer a particular way out. As they argue, it may be too strong to require that entities always have logically consistent beliefs. For instance, we might have many beliefs about matters of fact, and also believe it likely we are wrong about some of them. Following Joyce (1998), they introduce a weaker notion of coherence of beliefs. They show that the majority voting aggregation of logically consistent beliefs will always be coherent, and the aggregation of coherent beliefs will typically be coherent as well. In other words, if we demand less from majority voting as a means of judgment aggregation, we can get it.

In thinking about practical cases outside jury deliberation, we might ask whether the theory of judgment aggregation can apply to the increasingly common problem of how collaborating scientific authors should decide what statements to endorse. Solomon (2006), for instance, argues that voting might help scientists avoid “groupthink” arising from group deliberation. While Wray (2014) defends deliberation as crucial to the production of group consensus, Bright et al. (2018) point out that consensus is not always necessary (or possible) in scientific reporting. In such cases, they argue, majority voting is a good way to decide what statements a report will endorse, even if there is disagreement in the group.

3.5 Group Justification

Until this point, we have only looked at how a group belief may arise from, or be determined by, its member beliefs. We have not yet considered how—or whether—a group entity can achieve some significant level of epistemic “status”, or “achievement”. Believing something that is true is certainly worth something, but if one gets the truth only by luck or accident, that is not very significant. Similarly, simply having a set of coherent beliefs isn’t of unqualified significance, since mere coherence can arise from pure imagination coupled with inconsistency avoidance. Philosophers have long agreed that one of the most important types of epistemic attainment is knowledge. But what is knowledge? Almost everyone agrees that mere true belief isn’t knowledge. Again, true beliefs can sometimes arise fortuitously, by pure guessing or wishful thinking.

One popular way of strengthening the requirements for knowledge is to add a justification requirement. A true belief doesn’t per se qualify as knowledge unless the belief is justified. Justification is widely accepted as one species, or variety, of epistemic achievement. In addition to providing (arguably) an essential condition for knowledge, it seems to be an achievement, or attainment, in its own right, even when it doesn’t bring truth in along with it. For this reason, epistemologists have paid considerable attention to the nature of justification. Of course, most of this attention is concentrated on justification by individual believers. But, as we shall see, it is worth pursuing the possibility that group beliefs can also be evaluated as either justified or unjustified.

If the government of the United States believes (or were to believe) that there is a crisis of global warming, it would probably be justified in believing this, because of the overwhelming consensus of climate scientists to this effect. It is probably not required, however, that all members of a group must believe a given proposition in order that the group belief be justified, as Jennifer Lackey rightly says in criticizing the view of Frederick Schmitt (1994a: 265). It would make group justification too hard to come by (Lackey 2016: 249–250). But how, more precisely, should the requirement be specified?

Goldman (1979) advocates process reliabilism as an account of individual justification. He proposes an analogous approach to group justification in Goldman (2014). Under individual process reliabilism, a person is justified in believing a proposition W only if she believes W through using a generally reliable belief-forming process (or sequences of processes). In addition, if a person’s belief in W were produced by previous beliefs of hers, those other beliefs must also have been justified in order that her belief in W qualify as justified.

As indicated, Goldman’s approach to collective justifiedness is analogous to individual justifiedness. But how exactly is it analogous? First, members’ premises that contribute to the justification of a group’s belief must themselves be justified. A further requirement for group justification is that the group’s belief be caused by a type of belief-forming process that takes inputs from member beliefs in proposition p and outputs a group belief in p. The constraint on group justifiedness is a requirement that such a process type must be generally conditionally reliable. An example of such a process type might be a majoritarian process in which member beliefs (of the group) are aggregated into a group belief. The process is conditionally reliable only if, when it receives true input beliefs, most of the output beliefs are also true.

Lackey (2016), in critiquing Goldman’s theory, offers a number of challenging and insightful problems. Their numerosity and detail make it unfeasible to present or even summarize many of them. Let us consider one such objection.

Goldman advances a certain principle (GJ) which runs as follows: If a group belief in p is aggregated based on a profile of members’ attitudes toward p, then ceteris paribus the greater the proportion of members who justifiedly believe p and the smaller the proportion of members who justifiedly reject p, the greater the group’s level, or grade, of group justifiedness in believing p (Goldman 2014: 28). In other words, group justifiedness increases with a greater percentage of individual members with justified beliefs.

Lackey acknowledges that (GJ) “is not only intuitively plausible, it also is easily supported by applying an aggregative framework to group justifiedness” (2016: 361). Nonetheless, she proceeds to argue that (GJ) should be rejected. One major theme in her critique is that (GJ) falls prey to a paradox (on contradiction), which she calls the “Group Justification Paradox.” It questionably allows a group to end up justifiedly believing both a certain relevant proposition and its negation. Lackey hastens to acknowledge that not all contradictions, or inconsistencies, are necessarily fatal. For example, the well-known preface paradox is a case that generates inconsistent propositions, but it is nevertheless reasonable to have. An author’s apology in the preface is epistemically reasonable, given our grounds for holding that we all have our own fallibility (2016: 364). However, Lackey continues, the Group Justification Paradox admits no such approval. So the incidence of such contradictions does constitute a challenge to the proposed theory of group justification, even if the preface paradox does not present a problem.

3.6 Identifying Experts: A Case of Applied Social Epistemology

We return now to the basic form of social epistemology, in which individual cognizers seek information from other individuals. Here we are interested not in the concepts of justification or knowledge in general, but in particular applications. This might be called applied social epistemology. For example, how can one identify other individuals as sources of accurate information? A salient type of case is when one seeks information from an “expert,” where the seeker is himself/herself a layperson. Unfortunately, experts don’t always agree with one another. If you are offered advice by two different (putative) experts, but the two advisers disagree, which one should you trust, or believe?

What is meant by an “expert”? For present purposes, let us focus on factual subject matters (rather than matters of taste, for example). By an expert, then, we shall mean someone who—in a specified domain—possesses a greater quantity of (accurate) information than most other people do. A layperson, by contrast, is someone who has very little information in the specified domain, and who doesn’t take him/herself to have such information. The problem facing the layperson is how to select, among the disagreeing putative experts, the one that is best (Goldman 2001).

There are several possible methods by which the layperson might proceed. A first possible method is to seek statements or arguments from the competing (putative) experts to assess which one seems to be more knowledgeable, better-informed, and savvy (in the domain) as compared to his/her rivals. The problem here is: how can a layperson make an accurate assessment of the competing experts’ performance? By definition, the layperson is someone who is ill-informed on the subject. Moreover, experts often use language that is technical, arcane, rarified, or esoteric.

A second possible method is for the layperson to obtain information about the competing experts’ credentials. Where were the competing experts trained in the domain in question? What were the competing experts’ records of performance during their education? These are matters that the layperson may be unable to determine. And even if they are determined, is the layperson in a position to assess their significance?

A third method that a layperson might consider employing is how many other putative experts agree with a specified target expert on many of the questions in the target domain. If a given expert is an outlier on the issue in question, that might be a reason to avoid him/her. Conversely, if a large number of (putative) experts agree with the selected target, doesn’t that give extra weight to the latter’s promise as a sound advisor? Surely, a large number of concurring experts should provide strong support for a selected individual.

This is a tricky matter. There are many possible reasons why so many people in a field might agree, and such agreement doesn’t always signal that they are all correct. One possibility is that all the foregoing putative experts were trained by one and the same “guru”, who was a very persuasive and compelling figure. (Using a Bayesian analysis, it becomes clear that identifying an extra concurring believer need not strengthen one’s evidence as compared with a single believer. See Goldman (2001: 99–102).)

A fourth possible method is for the layperson to verify, by his/her own observation, that a candidate expert was correct in previous cases where he/she offered a view on the topic in question. The problem here is whether a layperson is capable of making such observations or determinations. It is possible in a selected range of cases. A layperson might consult with a broker to decide whether a certain investment is advisable. The broker gives her the go-ahead based on a prediction that the market in question will rise in the next three years. The layperson makes the investment, waits three years, and notes that the broker was right: the market did rise in those three years. The layperson couldn’t have made this prediction on the basis of her own knowledge. But she is able (after three years) to conclude that the putative expert was correct. Repeated instances of this kind would strengthen the support.

4. Formal Approaches to Social Epistemology

We have now seen some of the problems that face those who develop knowledge within a community. In recent years philosophers have turned to formal methods to understand some of these social aspects of belief and knowledge formation. There are broadly two approaches in this vein. The first comes from the field of formal epistemology, which mostly uses proof-based methods to consider questions that mostly originate within individual-focused epistemology. Some work in this field, though, considers questions related to, for example, judgment aggregation and testimony. The second approach, sometimes dubbed “formal social epistemology”, stems largely from philosophy of science, where researchers have employed modeling methods to understand the workings of epistemic communities. While much of this work has been motivated by a desire to understand the workings of science, it is often widely applicable to social aspects of belief formation.

Another distinction between these traditions is that while formal epistemologists tend to focus on questions related to ideal belief creation, such as what constitutes rationality, formal social epistemologists have been more interested in explaining real human behavior, and designing good knowledge-creation systems. We will now briefly discuss relevant work from formal epistemology, and then look at three topics in formal social epistemology.

4.1 Formal Epistemology in the Social Realm

As mentioned, formal epistemology has mostly focused on issues related to individual epistemology. This said, there is a significant portion of this literature addressing questions central to social epistemology. In particular: how should a group aggregate their beliefs? And: how should Bayesians update on the testimony of others?

As we have already seen, in aggregating propositional judgments groups of people can reach paradoxical outcomes as a result of majority voting. Let’s change focus, though, from propositional beliefs, to a more fine-grained notion of belief. Formal epistemologists more commonly discuss degrees of belief, or “credences”. These are numbers between 0 and 1 representing an agent’s degree of certainty in a statement. (For instance, if I think there is a 90% chance it is raining, my credence that it is raining is .9.) This representation changes the question of judgement aggregation to something like this: Suppose a group of people hold different credences, what should the group credence be?

In formal epistemology, this ends up being very closely related to the question of how an individual ought to update their credences upon learning the credences of others. If a rational group ought to adopt some aggregated belief, then it might also make sense for an individual in the group to adopt the same belief as a result of learning about the credences of his/her peers. In other words, the problems of judgment aggregation, peer disagreement, and testimony are entangled in this literature. (Though see Easwaran et al. (2016) for a discussion of distinctions between these issues.) We’ll focus here on belief aggregation, though we will comment throughout on these other issues.

In principle, there are many ways that one can go about aggregating credences or pooling opinions (Genest and Zidek 1986). A simple option is to combine opinions by linear pooling—taking a weighted average of credences. This averaging could respect all credences equally, or put extra weights on the opinions of, say, recognized experts. This option has some nice properties, such as preserving unanimous agreement, and allowing groups to aggregate over different topics independently (DeGroot 1974; Lehrer and Wagner 1981).[1]

In thinking about ideal knowledge creation though, we might ask how a Bayesian should update their credences in light of peer disagreement or how a group of Bayesians should aggregate beliefs. Bayes rule gives the rational way an agent should update a prior probabilistic credence in light of evidence to obtain a posterior credence. In general, if evidence appears that is more likely given A than B, a Bayesian will increase their credence that A in fact obtains upon observing that evidence. (So if I have a .9 credence that it is raining, and someone walks in wearing shorts and with perfectly dry hair, my credence in rain should decrease because my observation is more likely to occur on a sunny day than a rainy one.) Why is this approach rational? An individual who does not change credences according to Bayes rule can be Dutch booked—offered a series of bets that they will take, but that are guaranteed to lose money.

A Bayesian will not simply average across beliefs, except under particular assumptions or in special cases (Genest and Zidek 1986; Bradley 2007; Steele 2012; Russell et al. 2015). And a group that engages in linear averaging of this sort can typically be Dutch booked.

A fully-fledged Bayesian approach to aggregation demands that the final credence be derived by Bayesian updating in light of the opinions held by each group member (Keeney and Raiffa 1993). Notice, this is also what a Bayesian individual should do to update on the credences of others. To do this properly, though, is very complicated.[2] It requires prior probabilities about what obtains in the world, as well as probabilities about how likely each group member is to develop their credences in light of what might obtain in world. This will not be practical in real cases.

Instead, many approaches consider features that are desirable for rational aggregation, and then ask which simpler aggregation rules satisfy them. For instance, one thing a rational aggregation method should do (to prevent Dutch booking) is yield the same credence regardless of whether information is obtained before or after aggregating. For instance, if we all have credences about the rain, and someone comes in wearing shorts, it should not matter to the final group output whether 1) they entered and we all updated our credences (in a Bayesian way) and then aggregated them, or 2) we aggregated our credences, they entered, and we updated the aggregated credence (in a Bayesian way). Geometric methods, which take the geometric average of probabilities over worlds, yield this desirable property in many cases (Genest 1984; Dietrich and List 2015).[3] These methods proceed by multiplying (weighted) credences over worlds that might obtain and then renormalizing them to sum to 1.

One thing that geometric averaging does not do, though, is allow for credences over different propositions to be aggregated completely independently from each other. (Recall that this was something List and Pettit treated as a desideratum for judgment aggregation.) For instance, our beliefs about the probabilities of hail might influence how we will aggregate our beliefs over the probabilities of rain. Instead, a more holistic approach to aggregation is required. This is an important lesson for approaches to social epistemology which focus on individual topics of interest in addressing peer disagreement and testimony (Russell et al. 2015).

Another thing that some take to be strange about geometric averaging is that it sometimes will aggregate identical credences to a different group credence. For instance, we might all have credence .7 that it is raining, but our group credence might be .9. Easwaran et al. (2016) argue, though, that this often makes sense when updating on the credences of others—their confidence should make us more confident (see also Christensen 2009).[4]

This question of whether aggregated credences can be more extreme than individual ones echoes much earlier work bearing on the question: are groups smart? In 1785, the Marquis de Condorcet wrote an essay proving the following. Suppose a group of individuals form independent beliefs about a topic and they are each more than 50% likely to reach a correct judgement. If they take a majority vote, the group is more likely to vote correctly the larger it gets (in the limit this likelihood approaches 1). This result, now known as the “Condorcet Jury Theorem”, underlies what is sometimes called the “wisdom of the crowds”: in the right conditions combining the knowledge of many can be very effective.

In many cases, though, real groups are prone to epistemic problems when it comes to combining beliefs. Consider the phenomenon of information cascades, first identified by Bikhchandani et al. (1992). Take a group of agents who almost all have private information that Nissan stock is better than GM stock. The first agent buys GM stock based on their (minority) private information. The second agent has information that Nissan is better, but on the basis of this observed action updates their belief to think GM is likely better. They also buy GM stock. The third agent now sees that two peers purchased GM and likewise updates their beliefs to prefer GM stock. This sets off a cascade of GM buying among observers who, without social information, would have bought Nissan. The problem here is a lack of independence in the “vote”—each individual is influenced by the beliefs and actions of the previous individuals in a way that obscures the presence of private information. In updating on the credences of others, we thus may need to be careful to take into account that they might already have updated on the credences of others.

4.2 The Credit Economy

As noted, much of the work in formal social epistemology is by philosophers of science, who investigate scientific communities in particular. It will be useful to divide this literature into three categories: credit economy models of science, network epistemology models, and modeling approaches to diversity in epistemic communities.

Suppose you are a scientist choosing what to work on. There are two live options. One is more promising, and you suspect that if an advancement will be made, it will be on that problem. The other is less promising, but, as a result, fewer scientists are attracted to it. This means that should a discovery be made in that area, each scientist will be more likely to have made it.

The subfield of formal social epistemology arguably started with Philip Kitcher’s 1990 paper “The Division of Cognitive Labor”, which takes a rationality-based approach to the question of why scientists might divide labor effectively, even when they agree on which problems are most promising. By rationality-based approach, we mean that Kitcher represents scientists as utility-maximizers, in much the same way that economists represent people as utility-maximizers. The key innovation, though, is that scientists are assumed to derive utility from credit—a proxy for recognition and approbation of one’s scientific work, along with all the benefits (promotions, grants, etc.) that follow. The sociologist Robert Merton was one of the first to recognize the credit motives of scientists (Merton 1973). Models using this assumption are often called credit economy models.

Kitcher’s model shows that scientists in the sort of scenario sketched above will divide labor more effectively when they are motivated by credit than when they are pure truth-seekers. Truth seekers will each take the more promising approach. For credit-maximizers, once too many individuals work on the better problem, the expected credit for each scientist decreases to the point that some individuals will prefer to switch. Strevens (2003) extends Kitcher’s work by arguing that an existing feature of credit incentives, the priority rule, can lead to an even better division of labor. This is the rule, identified by Merton, which stipulates that credit will be allocated only to the scientist who first makes a discovery. In Strevens’s model, researchers incentivized by the priority rule divide labor in a highly efficient way compared to researchers incentivized by other credit schemes.

Not all researchers are as optimistic about the consequences of scientific credit norms like the priority rule. Romero (2017) points out, for example, that the benefits Kitcher and Strevens identify disappear in cases where results are not always replicable. (I.e., where, as in real scientific communities, any particular study could give a misleading result, and thus findings require replications before they can be considered “truth”.) In particular, the priority rule strongly disincentivizes scientists from performing replications because credit is so strongly associated with new, positive findings.

This debate reflects a deep question, going back as far as Du Bois (1898), and at the heart of much of the work in this section: what is the best motive for an epistemic community? Is it credit seeking or “pure” truth seeking? Or some combination of the two?

This sort of tension over the benefits and detriments of credit practices also plays out with respect to debates about scientific fraud. Starting with Merton many have argued that the desire to claim priority, and thus credit, drives fraud.[5] These arguments seem to suggest that scientists who ignore credit, and instead attempt to yield truth will do a better job. Bright (2017a), though, uses a model to point out that credit-seekers who fear retaliation may publish more accurate results than truth-seekers who are convinced of some fact, despite their experimental results to the contrary. In other words, a true believer may be just as incentivized to commit fraud as someone who simply seeks approval from their community.

We see this debate again over the Matthew effect, identified by Merton (1968). As Merton points out, pre-eminent scholars often get more credit for work than a less famous scholar would have gotten. Strevens (2006) argues that this follows the scientific norm to reward credit based on the benefit a discovery yields to science and society. Because famous scientists are more trusted, their discoveries do more good. Strevens claims that this norm of credit thus improves discovery in a community. Heesen (2017), on the other hand, uses a credit economy model to show how someone who gets credit early on due to luck may later accrue more and more credit because of the Matthew effect. When this kind of compounding luck happens, he argues, the resulting stratification of credit in a scientific community does not improve inquiry.

As should be clear, credit economy models help answer questions like: what is the best credit structure for an epistemic community? How do we promote truth? And: what credit incentives should be avoided?[6] Once we accept that epistemic communities are more than the sum of their individual parts, it is crucial to probe the incentive structures that members of these communities face in thinking about how best to shape them. As credit economy models show us, designing good epistemic communities is by no means a trivial task.

4.3 Network Epistemology Models

Another paradigm widely used by philosophers to explore social aspects of epistemology is the epistemic network. This kind of model uses networks to explicitly represent social or informational ties where beliefs, evidence, and testimony can be shared.

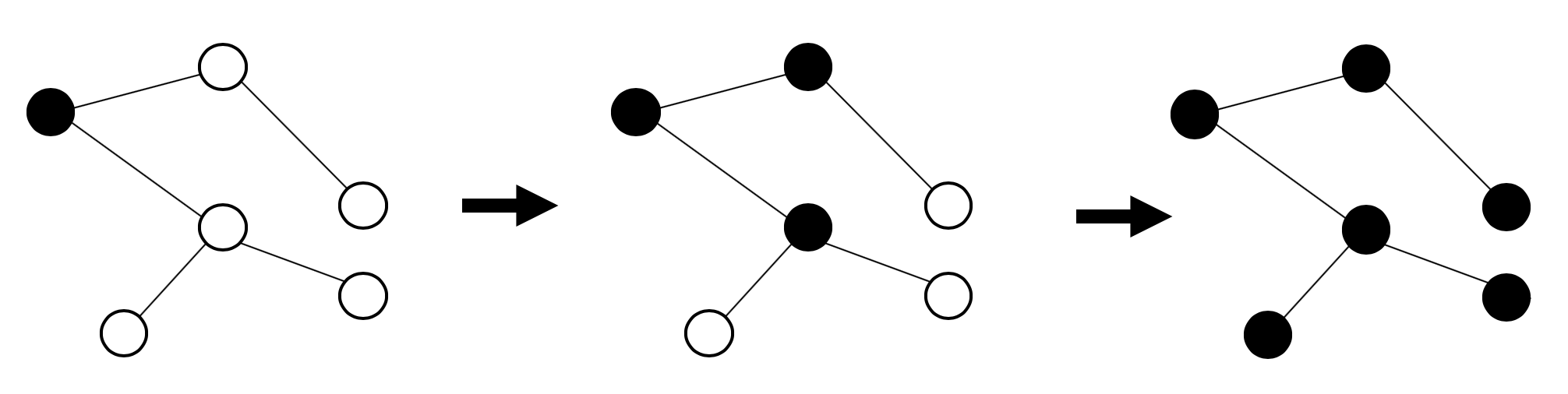

There are different ways to do this. In the social sciences generally, the most popular approach takes a “diffusion” or “contagion” view of beliefs. A belief or idea is transmitted from individual to individual across their network connections, much like a virus can be transmitted (Rogers 1962). Imagine you live in a farming community where a new species of large caterpillar has started decimating crops. Suppose you come to believe that this kind of caterpillar is poisonous. You will immediately tell your friends and neighbors what you have learned, they will tell their friends and neighbors, and so on. Figure 1 shows this. Black nodes represent those “infected” with an idea. It starts with a focal individual and spreads, virally, through the community.

Figure 1: A network contagion model where a focal individual infects others with a belief. [An extended description of figure 1 is in the supplement.]

In these diffusion/contagion models, though, the individuals do not gather evidence from the world, share evidence with each other, or form beliefs in any sort of rational way. For this reason, philosophers of science have tended to use the network epistemology framework instead. This framework was introduced by economists Bala and Goyal (1998) to model how individuals learn from neighbors. It was imported to philosophy by Kevin Zollman, who first used it to represent scientific communities (Zollman 2007, 2010).

Now imagine the same caterpillar example, but where the individuals involved form evidence-based beliefs. One becomes suspicious that the caterpillar is poisonous, and tests to see if this is true. She shares the evidence she gathered (not just her belief) with those she is connected to. Her neighbors, on the basis of this evidence, themselves become more suspicious that the caterpillar is dangerous, and test for themselves. They, in turn, share the evidence they gather with their neighbors. Beliefs can still spread through a network, but now they do so on the basis of at least semi-rational belief-forming mechanisms.

In more detail: network epistemology models start with a collection of agents on a network, who choose from some set of options. One option is preferable to the rest, but to find out which this is, the agents must actually try them and see what results. These could represent choices of action-guiding theories (like “caterpillars are safe” and “caterpillars are poisonous” or else “vaccines are safe” and “vaccines cause autism”). They could alternatively represent research approaches that yield different levels of scientific success.

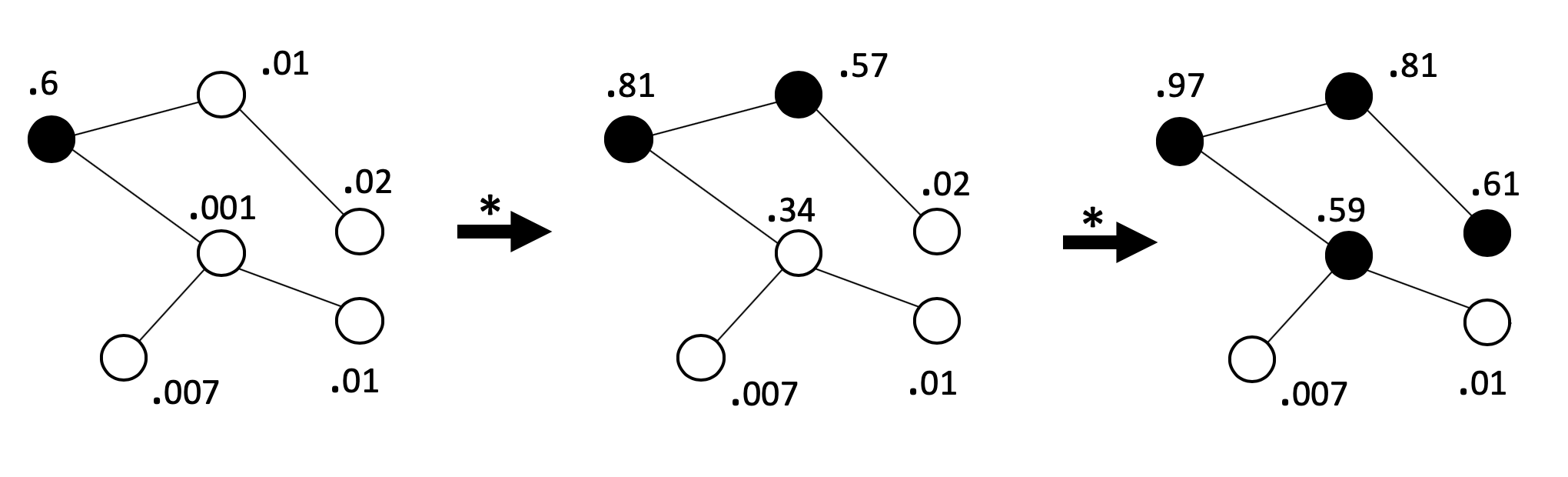

Agents have beliefs about which option is preferable, and change these beliefs in light of the evidence they gather from their actions. In addition, they also update on evidence gathered by neighbors in the network, typically using some version of Bayes’ rule. It is in this sense that agents are part of an epistemic community. Figure 2 shows what this might look like. The numbers next to each agent represent their degree of belief in some proposition like “vaccines are safe”. The black agents think this is more likely than not. As this model progresses these agents gather data, which increases their neighbors’ degrees of belief in turn.

Figure 2: Agents in a network epistemology model use their credences to guide theory testing. Their results change their credences, and those of their neighbors. [An extended description of figure 2 is in the supplement.]

Communities in this model can develop beliefs that the better theory (vaccines are safe) is indeed better, or else they can pre-emptively settle on the worse theory (vaccines cause autism) as a result of misleading evidence. Generally, since networks of agents are sensitive to the evidence they gather, they are more likely to figure out the “truth” of which is best (Zollman 2013; Rosenstock et al. 2017).

Zollman (2007, 2010) describes what has now been dubbed the “Zollman effect” in these models; the surprising observation that it is sometimes worse for communities to communicate more (see also, Grim 2009). In particular, groups with more network connections will be generically less likely to arrive at a correct consensus. The group needs to entertain all the possible options long enough to gather good evidence and settle on the best one. In tightly connected networks, misleading evidence is widely shared, and may cause the community to pre-emptively settle on a poor theory.

Mayo-Wilson et al. (2011, 2013) likewise defend a surprising thesis, which supports central claims from social epistemology espoused by Goldman (1999). They use epistemic network models, to support the so called “independence thesis”—that rational groups may be composed of irrational individuals, and rational individuals may constitute irrational groups. For instance, consider a learner who tests some preferred theory. Alone, she may fail to test other successful theories, but a community representing a full diversity of preferred theories will be expected to learn which is best.

One thing we know about human learners is that they have various cognitive and social biases that influence how they take up information from peers. One of these is conformity bias, or a tendency to espouse the views of group members, even if one secretly disagrees with them (Asch 1951). Weatherall and O’Connor (2018, Other Internet Resources) show how conformity can prevent the adoption of successful beliefs because agents who conform to their neighbors are often unwilling to pass on good information that goes against the grain. Mohseni and Williams (2019, Other Internet Resources) similarly find that conformity slows learning, likewise because it prevents agents from sharing information, and because group members who expect this are less trusting of their peers.[7]

Several authors have used variants on the epistemic network model to explore the phenomenon of “polarization” within groups.[8] Both Olsson (2013) and O’Connor and Weatherall (2018) consider versions of the model where actors place less trust in the evidence (or testimony) of those who do not share their beliefs. A vaccine skeptic, for instance, might be skeptical of evidence shared by a physician, but accepting of evidence from a fellow skeptic. This can lead to stable, polarized camps that each ignore evidence and testimony coming from the other camp.[9] The two sets of results just described help answer the question: in light of real social and learning biases, what can go wrong? And: how can we shape good epistemic networks to counteract these biases? (These questions tie into how we should understand democracy in light of social epistemology.)

One of the most interesting recent uses of the network epistemology framework involves investigating the role of pernicious influencers, especially from industry, on epistemic communities. Holman and Bruner (2015) look at a network model where one agent shares only fraudulent evidence meant to support an inferior theory. As they show, this agent can keep a network from reaching successful consensus by muddying the water with misleading data. Holman and Bruner (2017) and Weatherall et al. (forthcoming) use network epistemology models to explore specific strategies that industry has used to influence scientific research. As Holman and Bruner show, industry can shape the output of a community through “industrial selection”—funding only agents whose methods bias them towards preferred findings. Weatherall et al. add a group of “policy makers” to the model, to show how a propagandist can mislead these public agents simply by sharing a biased sample of the real results produced in an epistemic network. For example, Big Tobacco might gather up real, independent studies that happen to find no link between smoking and cancer, and share these widely (Oreskes and Conway 2011). Together these two papers give insight into how strategies that do not involve fraud can shape scientific research and mislead the public.

One truth about epistemic communities is that relationships matter. These are the ties that ground testimony, disagreement, and trust. Epistemic network models allow philosophers to explore processes of influence in social networks, yield insights into why social ties matter to the way communities form beliefs, and think about how to create better knowledge systems.

4.4 Modeling Diversity in Epistemic Communities

Diversity has emerged several times in our discussion of formal social epistemology. Credit incentives can encourage scientists to choose a diversity of problems. In network models, a transient diversity of beliefs is necessary for good inquiry. Let us now turn to models that tackle the influence of diversity more explicitly.[10] It has been suggested that cognitive diversity benefits epistemic communities because a group where members start with different assumptions, use different methodologies, or reason in different ways may be more likely to find truth.

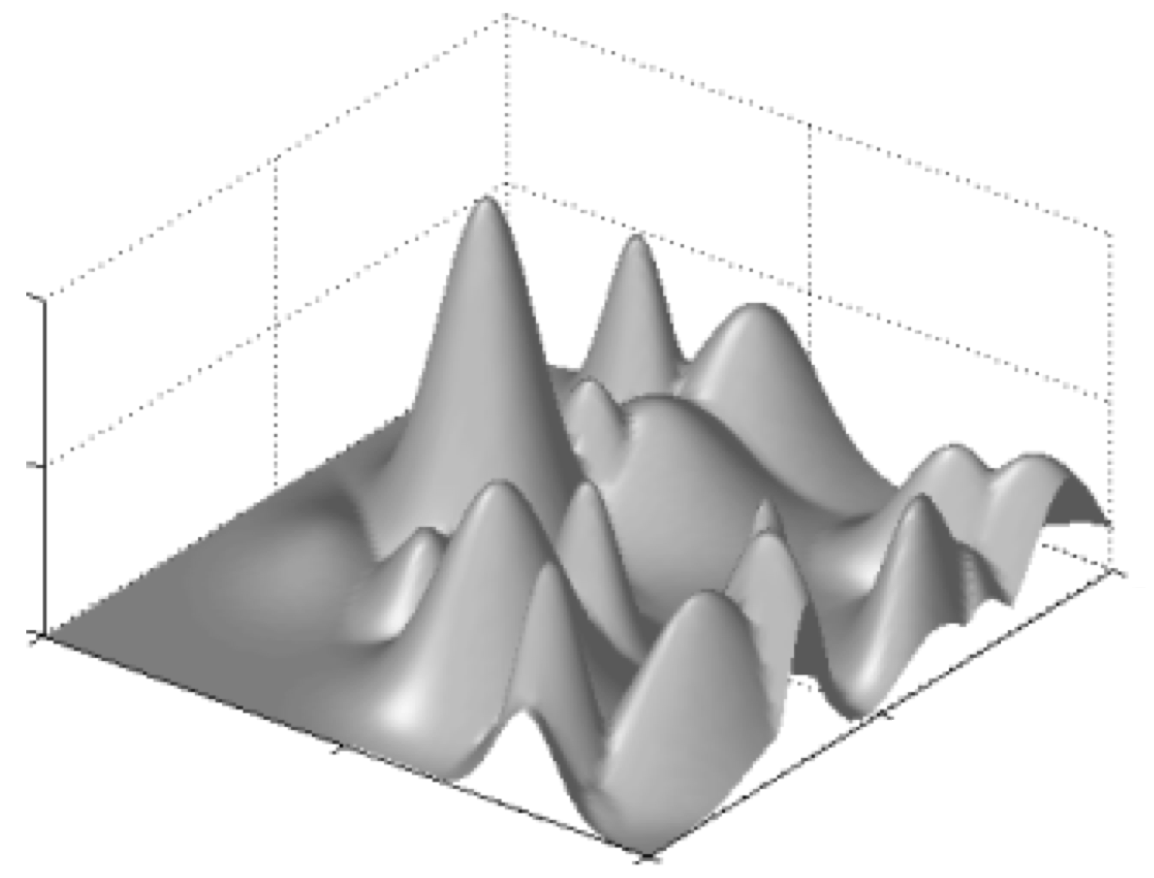

Weisberg and Muldoon (2009) introduce a model where actors investigate an “epistemic landscape”—a grid where each section represents a problem in science, of varying epistemic importance. Figure 3 shows an example of such a landscape. Scientists are randomly scattered on the landscape, and follow search rules that are sensitive to this importance. Investigators can then ask: how well did scientists do? Did they fully search the landscape? Did they find the peaks?

Figure 3: An epistemic landscape. Location represents problem choice, and height represents epistemic significance.

Weisberg and Muldoon use the model to argue that a combination of “followers” (scientists who work on problems similar to other scientists) and “mavericks” (who prefer to explore new terrain) do better than either group alone; i.e., there is a benefit to cognitive diversity. Their modeling choices and main result have been convincingly criticized (Alexander et al. 2015; Thoma 2015; Poyhönen 2017; Fernández Pinto and Fernández Pinto 2018), but the framework has been co-opted by other philosophers to useful ends. Thoma (2015) and Poyhönen (2017), for instance, show that in modified versions of the model, cognitive diversity indeed provides the sort of benefit Weisberg and Muldoon hypothesize.[11]

Hong and Page (2004) use a simple model to derive their famous “Diversity Trumps Ability” result. Agents face a problem modeled as a ring with some number of locations on it. Each location is associated with a number representing its goodness as a solution. An agent, in the model, is represented as a finite set of “heuristics”, or integers, such as ⟨3, 7, 10⟩. Such an agent is placed on the ring, and can see the locations 3, 7, and 10 spots ahead of their current position. They then move to whichever has the highest number until they reach a location where they can no longer improve their score.

The central result is that randomly selected groups of agents who tackle the task together tend to outperform groups created of top performers. This is because the top performers have similar heuristics, and thus gain relatively little from group membership, whereas random agents have a greater variety of heuristics. This result has been widely cited, though there have been criticisms of the model either as insufficient to show something so complicated, as lacking crucial representational features, or as failing to show what it claims (Thompson 2014; Singer 2019).

To this point we have addressed cognitive diversity. But we might also be interested in diversity of social identity in epistemic communities. Social diversity is an important source of cognitive diversity, and for this reason can benefit the functioning of epistemic groups. For instance, different life histories and experiences may lead individuals to hold different assumptions and tackle different research programs (Haraway 1989; Longino 1990; Harding 1991; Hong and Page 2004). If so, then we may want to know: why are some groups of people often excluded from epistemic communities like those in academia? And what might we do about this?

In recent work, scholars have used models of bargaining to represent academic collaboration. They have shown 1) how the emergence of bargaining norms across social identity groups can lead to discrimination with respect to credit sharing in collaboration (Bruner and O’Connor 2017; O’Connor and Bruner 2019) and 2) why this may lead some groups to avoid academia, or else cluster in certain subfields (Rubin and O’Connor 2018). In the credit-economy tradition, Bright (2017b) explains why a noted phenomenon—that women tend to publish fewer papers than men—may not indicate a gap in quality of research. As he points out, anticipation of rejection may lead women to overshoot by producing papers of higher quality than necessary for publication. This gap contributes to the underrepresentation of women in some disciplines.

As we have seen in this section, models can help explain how and when cognitive diversity might matter to the production of knowledge by a community. They can also tell us something about why epistemic communities often, nonetheless, fail to be diverse with respect to social identity.

5. Social Epistemology and Society

Let us now move on to see how topics from social epistemology intersect with important questions about the proper functioning of democratic societies, and questions about the ethics of social knowledge and learning.

5.1 Truth-Seeking in the Pursuit of Democracy

In our portrayal of social epistemology thus far, several different mosaics have been sketched. In some cases, a single epistemic agent seeks epistemic help from another agent. In other cases, a collective agent seeks answers to questions using its members in a collaborative fashion. A third kind of case, which arose especially in the last section, is what we shall call a “system-oriented” or “institution-oriented” application of social epistemology.

By a “system” we mean some entity with a multiplicity of working “parts” and multiple goals that the system aims to achieve. A question that arises, quite frequently, is how best to design a system that will maximize the attainment, or satisfaction, of its (most important) goals over time. As we have seen, this is a question that philosophers have attempted to answer with respect to the structure of scientific communities. Another good example of such systems are political systems, especially democratic political systems. There are many current democratic theorists who place much emphasis on the epistemological, or epistemic, properties of democratic institutions.

Elizabeth Anderson (2006) focuses on the question of how the epistemic properties of democratic systems can be designed to attain the best possible form of democracy. She provides three epistemic models of democracy: the Condorcet Jury Theorem, the Diversity Trumps Ability result, and John Dewey’s experimentalism (see Landemore 2011). Anderson plumps for Dewey’s experimentalist approach. He highlights the importance of bringing together citizens from different walks of life to define, through discussion, the principal problems they confront and what might be the most promising solutions. Their different walks of life constitute, in effect, a range of experiments that can help them collectively appraise alternative solutions, thus taking advantage of cognitive diversity. Anderson provides a convincing illustration of Dewey’s thesis by relating how women in a South Asian village were able to manage their forests better when they were given opportunities to make fuller use of their “situated knowledge” (see Agarwal 2000).

When we contemplate the meaning of democracy, we often mean (as a starting point, anyway) a governmental system that features equal voting rights for all citizens. A little reflection, however, readily indicates how shallow a role is played by mere voting rights. A citizen may be entitled to cast a vote for any of the candidates on the ballot. But this will not help the voter promote positive results (positive by her lights) if she has misguided views of what specific candidates for office would do if they were actually elected, or about what policy measures will be effective (for details, see Goldman 1999: 315–348).

This raises the question of just how informed or misinformed ordinary voters are, and what prospects there are for improving the present situation. Many political scientists have shown that American voters are strikingly uninformed with respect to textbook facts about their government. Nonetheless, there are some rays of light. Several books argue that ordinary citizens can make sense of their political world despite a lack of detailed information about policies and candidates (see Berelson, Lazarsfeld, & McPhee 1954, and Katz & Lazarsfeld 1955; cited in Goldman 1999). One semi-optimistic idea is that of a two-step flow of communication from well-informed “opinion leaders” to the public at large. This approach suggests that ordinary citizens—even those who pay little attention to the details of politics—can learn what they need to know to make suitable choices by listening to the opinions of experts or news junkies. Cues and informational “shortcuts” are available that can lead them to the same answers that more informed citizens arrive at (cf. Goldman 1999: 318).

If this account is correct, it suggests that a wide range of citizens can make fairly “accurate” voting decisions if two conditions hold: (1) there are political experts whose knowledge enables them to pinpoint who would be good electoral choices relative to specifiable citizens; and (2) these initially less-informed citizens are capable of identifying who are (some of) the genuine experts and who are not. An ability to recognize genuine expertise in political matters can play a significant role in promoting the kind of democratic success described above. As noted, though, it can be difficult for laypeople to decide which experts to trust. And as we saw in the last section, in our discussion of industrial influence on public belief, there are forces that work to undermine the functioning of democracy, and that often bring us away from this more optimistic picture. In the next section we will briefly discuss some related issues.

5.2 Misinformation on the Internet

The latest challenge confronting the informational state of the public is the accelerating spread of misinformation and disinformation on the internet. On Twitter falsehoods spread further and faster than the truth (Temming 2018a,b). In the run-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the most popular bogus articles got more Facebook shares, reactions, and comments than the top real-news stories, according to a BuzzFeed News analysis. And, as many have documented, online misinformation and disinformation in a wide variety of forms have created serious issues vis-à-vis public belief and democratic functioning.

In trying to tackle the spread of misinformation, many online platforms have implemented algorithms. For instance, in response to “fake news”, programmers have built automated systems that aim to judge the veracity of online stories. Researchers explore which features of an article are the most reliable identifiers of fake news (Temming 2018b: 24). Clearly, these sorts of tools have some promise as part of the enterprise of social epistemology. But their power to discriminate true stories from false ones still has limited reliability. Furthermore, as O’Connor and Weatherall (2019) point out (drawing on the work of Holman (2015) who looks at arms races between pharmaceutical companies and regulators) online misinformation constitutes a kind of arms race. As platforms and programmers and governments develop tools to fight it, the purveyors of misinformation (the Russian state, various partisan groups, advertisers, trolls, etc.) will develop new methods of shaping public belief.

All ill-informed populace, as noted, may not be able to effectively represent their interests in a democratic society. In order to protect democratic functioning, going forward it will be necessary for those fighting online misinformation to keep adapting with the best tools and theory available to them. This includes understanding social aspects of knowledge and belief formation. In other words, social epistemology has much to say to those faced with the challenging task of protecting democracy from misinformation.

5.3 Moral Social Epistemology

Some recent writers seek to expand the notion of social epistemology by incorporating moral or ethical elements. Miranda Fricker (2007) in particular has made significant contributions to this literature. Fricker introduces the notion of “epistemic injustice,” which arises when somebody is wronged in their capacity as a knower. An easily recognizable form of such injustice is when a person or a social group is unfairly deprived of knowledge because of their lack of adequate access to education or other epistemic resources. Fricker’s work also focuses on two less obvious forms of epistemic injustice. The first is testimonial injustice, which occurs when a speaker is given less credibility than she deserves because the hearer has prejudices about a social group to which the speaker belongs. The second kind is hermeneutical injustice. This occurs when, as a result of a group being socially powerless, members of the group lack the conceptual resources to make sense of certain distinctive social experiences. For instance, before the 1970s, victims of sexual harassment had trouble understanding and describing the behavior of which they were the victims, because the concept had not yet been articulated. Christopher Hookway (2010) builds on Fricker’s work and argues that there are other forms of epistemic injustice that do not involve testimony or conceptual resources

These issues are relevant epistemological ones for those in democratic societies. Epistemic injustices may leave some members of society ill-equipped to engage in the debates that fuel a well-functioning democracy. Testimonial injustice may prevent the spread of important information and perspectives through a community.

As we saw in the last section, misinformation can also pose epistemic threats to democratic functioning. With respect to internet misinformation, we might ask: do we have a right to protection against such misinformation? Is it morally acceptable, or even morally mandatory, for internet platforms, or government bodies, to protect public belief by regulating and limiting misinformation? There are deep political and moral issues here that we cannot possibly cover in this entry. But we will note a fundamental tension that is relevant. Free speech is protected in most democratic societies, but part of the defense of free speech by thinkers like Mill (1859 [1966]) is that it is crucial for freedom of thought. Once we recognize that human beliefs are deeply social, and do not always follow Descartes’ model of the individual, fully rational reasoner, we might acknowledge that some sorts of speech interfere with our freedom of thought, and in some cases we may need to decide to protect one in lieu of the other.

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Bina, 2000, “Conceptualising Environmental Collective Action: Why Gender Matters”, Cambridge Journal of Economics, 24(3): 283–310. doi:10.1093/cje/24.3.283

- Alexander, Jason McKenzie, Johannes Himmelreich, and Christopher Thompson, 2015, “Epistemic Landscapes, Optimal Search, and the Division of Cognitive Labor”, Philosophy of Science, 82(3): 424–453. doi:10.1086/681766

- Anderson, Elizabeth, 2006, “The Epistemology of Democracy”, Episteme: A Journal of Social Epistemology, 3(1): 8–22. doi:10.1353/epi.0.0000

- Asch, S. E., 1951, “Effects of Group Pressure upon the Modification and Distortion of Judgments”, in Groups, Leadership and Men; Research in Human Relations, Harold Steere Guetzkow (ed.), Oxford, England: Carnegie Press, 177–190.

- Avin, Shahar, 2018, “Policy Considerations for Random Allocation of Research Funds”, RT. A Journal on Research Policy and Evaluation, 6(1). doi:10.13130/2282-5398/8626

- –––, 2019, “Centralized Funding and Epistemic Exploration”, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, 70(3): 629–656. doi:10.1093/bjps/axx059

- Bala, Venkatesh and Sanjeev Goyal, 1998, “Learning from Neighbours”, Review of Economic Studies, 65(3): 595–621. doi:10.1111/1467-937X.00059

- Berelson, Bernard, Paul F. Lazarsfeld, and William N. McPhee, 1954, Voting; a Study of Opinion Formation in a Presidential Campaign, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Bikhchandani, Sushil, David Hirshleifer, and Ivo Welch, 1992, “A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades”, Journal of Political Economy, 100(5): 992–1026. doi:10.1086/261849

- Bird, Alexander, 2014, “When Is There a Group That Knows?”, in Lackey 2014: 42–63. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665792.003.0003

- Bradley, Richard, 2007, “Reaching a Consensus”, Social Choice and Welfare, 29(4): 609–632. doi:10.1007/s00355-007-0247-y

- Bramson, Aaron, Patrick Grim, Daniel J. Singer, William J. Berger, Graham Sack, Steven Fisher, Carissa Flocken, and Bennett Holman, 2017, “Understanding polarization: Meanings, measures, and model evaluation”, Philosophy of Science, 84(1): 115–159.

- Briggs, Rachael, Fabrizio Cariani, Kenny Easwaran, and Branden Fitelson, 2014, “Individual Coherence and Group Coherence”, in Lackey 2014: 215–239. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199665792.003.0010

- Bright, Liam Kofi, 2017a, “On Fraud”, Philosophical Studies, 174(2): 291–310. doi:10.1007/s11098-016-0682-7

- –––, 2017b, “Decision Theoretic Model of the Productivity Gap”, Erkenntnis, 82(2): 421–442. doi:10.1007/s10670-016-9826-6

- Bright, Liam Kofi, Haixin Dang, and Remco Heesen, 2018, “A Role for Judgment Aggregation in Coauthoring Scientific Papers”, Erkenntnis, 83(2): 231–252. doi:10.1007/s10670-017-9887-1

- Bruner, Justin P., 2013, “Policing Epistemic Communities”, Episteme, 10(4): 403–416. doi:10.1017/epi.2013.34