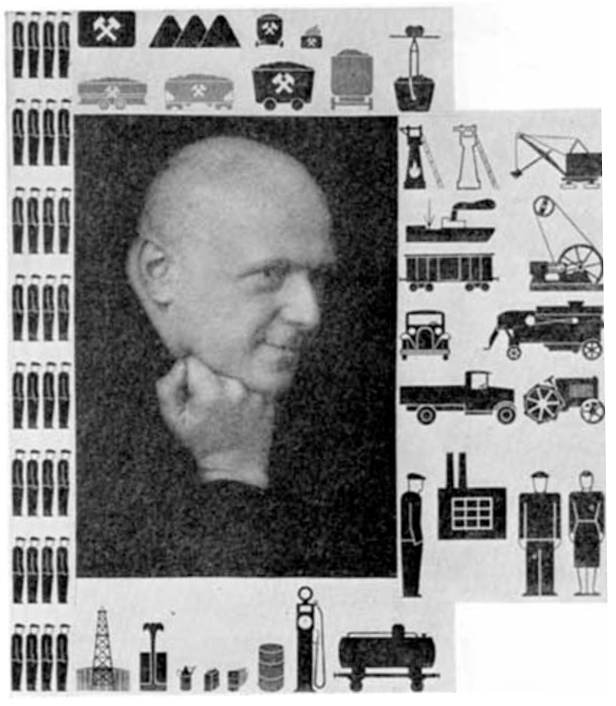

Otto Neurath

Source: Survey Graphic, 25 (November 1936): 618.

Neurath was a social scientist, scientific philosopher and maverick leader of the Vienna Circle who championed ‘the scientific attitude’ and the Unity of Science movement. He denied any value to philosophy over and above the pursuit of work on science, within science and for science. And science was not logically fixed, securely founded on experience nor was it the purveyor of any System of knowledge. Uncertainty, decision and cooperation were intrinsic to it. From this naturalistic, holistic and pragmatist viewpoint, philosophy investigates the conditions of the possibility of science as apparent in science itself, namely, in terms of physical, biological, social, psychological, linguistic, logical, mathematical, etc. conditions. His views on the language, method and unity of science were led throughout by his interest in the social life of individuals and their well-being. To theorize about society is inseparable from theorizing for and within society. Science is in every sense a social and historical enterprise. It is as much about social objectives as it is about physical objects, and about social realizations as much as about empirical reality. Objectivity and rationality, epistemic values to constrain scientific thought, were radically social. The topics of political economy and visual education, based on the ISOTYPE language, are concrete legacies that have regained relevance, urgency and interest. These are discussed in the supplements, Political Economy and Visual Education.

- 1. Biographical sketch

- 2. From economic theory to scientific epistemology

- 3. Neurath’s place in logical empiricism: physicalism, anti-foundationalism, holism, naturalism, externalism, pragmatism

- 4. Unity of Science and the Encyclopedia Model

- 5. Philosophy of psychology, education, and the social sciences

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

1. Biographical sketch

Otto Neurath was born on 10 December 1882 in Vienna. He was the son of Gertrud Kaempffert and Wilhelm Neurath, a Hungarian Jewish political economist and social reformer, and was born Roman Catholic. Initially studying in Vienna philosophy, mathematics and physics and then history, philosophy and economics (he formally enrolled for classes at the University of Vienna only for two semesters in 1902-3), he followed the social scientist Ferdinand Tönnies’s advice to move to Berlin, where he received a doctoral degree in history of economics in 1906. He studied under Eduard Meyer and Gustav Schmoller and he was awarded the degree for two studies of economic history of antiquity, one on Cicero’s De Officiis and the other with an emphasis on the non-monetary economy of Egypt. In his biographical précis at the end his doctoral dissertation on Cicero he mentioned having studied mathematics, natural science and philosophy in Vienna with the following: von Escherich, Haberda, Haffner, Hartl, Jodl, Kohn, Kretschmer, von Lang, Lieben, Mertens, Müch, Müllner, Oberhummer, Penck, Schindler and von Schroeder; and in Berlin, he studied national economy, history and philosophy with the following: von Bortkiewicz, Breysig, Brunner, Eberstadt, Hintze, Jastrow, Landau, Menzer, Meyer, Paulsen, Schmoller, Simmel, and Wagner. He also thanked his studies of the ideas of the logician Gregor Itelson, Wilhelm Neurath’s colleague and mathematician Oskar Simony and the social scientist Ferdinand Tönnies.

His first publications were in logic, a subject he had formally learned at the University of Vienna from Laurenz Müllner and possibly Friedrich Jodl, and in the history of political economy, on which his father had also written. The papers on logic (see below) examined different kinds of identities and the principle of duality stimulated by Schröder; they included one paper co-authored with his friend and second wife, Olga Hahn, sister of the mathematician Hans Hahn. In the history of political economy, topics included the history of money and economic organizations in antiquity, and his publications included textbooks and readers either co-authored or co-edited with his first wife Anna Schapire-Neurath. Not surprisingly, his subsequent theorizing on the social sciences and his contributions to debates in logical empiricism integrated both disciplines. With the mathematician Hans Hahn and the physicist Philip Frank, around 1910 Neurath formed in Vienna a philosophical discussion group devoted to the philosophical ideas about science of Vienna’s phenomenologist Ernst Mach and the French conventionalists Pierre Duhem, Abel Rey and Henri Poincaré. A great deal of philosophical and scientific concerns and insight were already in place in Neurath’s thinking and projects. With a grant from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a subsequent study of the Balkan wars before World War I led to his theory of war economy as a natural (non-monetary) economy, or economy in kind.

In 1919 the short-lived Bavarian socialist government (November 1918-April 1919) appointed him head of the Central Planning Office. The fall of the subsequent Bavarian Soviet Republic in May 1919 got him expelled from his junior post teaching economic theory at Heidelberg University, where he had received his Habilitation in 1917. His program for full socialization was inspired by his studies of war economics and based on his theory of natural economy and a holistic requirement to bring different institutions and kinds of knowledge together in order to understand, predict and control the complex phenomena of the social world. From 1921 until 1934 Neurath participated actively in the development of Vienna’s socialist politics, especially in housing and adult education (on his political life, see Sandner 2014). He established the Social and Economic Museum of Vienna, where he developed and applied the ‘Vienna method’ of picture statistics and the ISOTYPE language (International System of Typographic Picture Education) (see the supplementary document on Visual Education). Like the thought of other Viennese philosophers such as Wittgenstein and Popper, Neurath’s philosophy was inextricably linked to pedagogical theory, critique of language and, in Popper’s case, political thought. In 1928, with members of the Austrian Freethinkers Association and the Vienna City Council and the scientifically-trained members of the informal circle around the current holder of Mach’s University Chair, the philosopher Moritz Schlick (1924-29), Neurath helped found the Verein Ernst Mach, the Ernst Mach Association for the Promotion of Science Education. The publication in 1929 of an intellectual manifesto gave way to the formation of the Vienna Circle, whose narrower goal was the articulation and promotion of a scientific world-conception and logical empiricism (on the Viennese intellectual landscape, see Stadler 2001).

Subsequently, when in 1934 the Austrian government allied itself with the Nazi government in Germany, Neurath fled to the Netherlands. As a result, his local, Viennese, socialist Enlightenment project turned into an internationalist, intellectual and social-political project. He created the International Foundation for Visual Education in The Hague, with his assistants from Vienna, and spearheaded the International Unity of Science movement. The latter, inspired by a tradition culminating in the Enlightenment’s French Encyclopedists, launched the project of an Encyclopedia of Unified Science. Together with the pictorial languages, the scientific encyclopedia would promote scientific and social cooperation and progress at an international level. After Austria became part of the German Reich in 1938, even though living in the Netherlands, Neurath was considered a German citizen and a ‘half-Jew’ and he was not allowed to marry his ‘Aryan’ assistant Marie Reidemeister—after his second wife, Olga, had died in 1937. During this period, he travelled abroad, including the United States, where logical empiricism had become entangled with the Cold War political and intellectual debates and witch hunts (on the Cold War phase, see Reich 2005). Carnap and Charles Morris at the University of Chicago acted as his co-editors of the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science. New York leftist intellectuals hosted him as an intellectual and political ally. And his maternal first cousin Waldermar Kaempffert, influential editor for The New York Times and Popular Science, introduced him as an international reformer and visionary, praising his science-oriented intellectual, social and educational ideas, especially his contribution to unity of science and visual language (see Reisch 2019). After the Nazi invasion of the Netherlands in 1940, Otto Neurath and Marie Reidemeister fled to England, on the small Seaman’s Hope. After nine months in an internment camp they resumed activities related to the Isotype language and the unity of science. He died in Oxford on 22 December 1945 (on activities in the camp see Henning 2019; on activities after see Körber 2019 and Tuboly 2019).

2. From economic theory to scientific epistemology

During the Vienna Circle years, Neurath introduced in the new context views which he developed and generalized from his earlier social theory, only now in terms of the debates on scientific epistemology that came to characterize logical empiricism: (1) a notion of theorizing in natural and social sciences, including history, based on the exploration of combinatorial possibilities and models; (2) the logical under-determination and conventional and pragmatic aspect of decision-making in the methodology of evaluation and choice of data and hypotheses; (3) the social, cooperative dimension of scientific research (‘the republic of scientists’); and, connectedly, (4) an argument for a holistic approach to scientific knowledge in the form of unified science as a tool for successful prediction and engineering (mechanical, electrical and social) of events and their evolution in a world understood as a complex of factors (Cat et al. 1991 and 1996)—where an alternative model of unification would replace the standard set by the reductive, precise and abstract monetary units of the market model (Nemeth 1991).

This engineering value of unity applied equally to political governance and scientific action, since both are collective and pragmatic endeavors. According to Neurath, ‘scientific theories are sociological events’ (Neurath 1932a/1983, 88), and, since ‘our thinking is a tool’, in this case the ‘modern scientific world-conception’ aims to ‘create a unified science that can successfully serve all transforming activity’ (Neurath 1930/1983, 42). In both cases, Neurath noted, ‘common planned action is possible only if the participants make common predictions’ and group predictions yield more reliable results; therefore, he concluded, ‘common action presses us toward unified science’ (Neurath 1931/1973, 407). Indeed, all along, for Neurath scientific attitude and solidarity (and socialism) go together (Neurath 1928/1973, 252).

During the 1910s Neurath engaged the intellectual issues of holism and conventionalism raised both by the models of economies in kind —the Balkan war economies and socialization of the Bavarian economy—and by Duhem’s philosophy of scientific testing. Not surprisingly, his intellectual attitude led him to the recurrent dismissal of the myth of the fundamental epistemological and political value of isolated statements (hypotheses) and isolated individuals (citizens, scholars). The problem of unity of the sciences would become another problem of coordination and cooperation, social and intellectual (see above), of scholars and statements, and Neurath presented it in just those terms (Neurath 1936/1983).

Neurath developed and generalized his early practical, theoretical and meta-theoretical concerns about social theory (with his talk of a ‘universal science’ in 1910, a ‘unified construction of economic science’ in 1917 and a ‘unified program’ for socialization in 1919) as a philosophy of the human sciences. These included psychology and sociology, which he treated in contrast with the natural sciences. His study of the foundations of the social sciences extended to import normative constraints set by logical empiricism, e.g., the emphasis on foundations and the logical and empiricist considerations with respect to physicalism. This contribution determined his qualifications to ideals of unity of the sciences, especially involving the relation between the natural and the human sciences, and to ideals of shared scientific methodology.

The new framework for philosophy, and meta-theory, was characterized by an anti-metaphysical attitude towards linguistic and otherwise formal, rather than material, entities. For Neurath, social theory points not only to the contingent historical and social nature of language; it also points to a more naturalistic attitude towards language—and knowledge—in connection with its social roots and uses. As a result, his early considerations of social theory and values yielded a model of language of theory and observation that were meant to do justice to the social and voluntaristic dimensions of unity, rationality, and objectivity in the language and methodology of the sciences. Next, in the rest of this section, I provide details of the connection I have indicated.

In the early 1930s Neurath would point to weakness and incompleteness of the logical and linguistic relations between different kinds of scientific statements—mainly due to the unavoidable presence of vague cluster-concepts, or congestions (Ballungen). They consisted in linguistic manifestation of the ineliminable social, everyday, non-theoretical vague elements of language and of the intrinsic complexity of the world discussed in the German metaphysical literature and the later socialist debates (Cat 1995 and Cartwright et al. 1996). Since then his notion of unity is phrased in terms of an anti-reductionistic and anti-systematic—anti-axiomatic—‘encyclopedia model’, by establishing cross-connections among disciplines, as in a Crusonian archipelago: a ‘great, rather badly coordinated mass of statements’ in which at best ‘systems develop like little islands, which we must try to enlarge’ (Neurath 1936/1983, 153).

The connection between the arguments and positions in 1930s scientific epistemology or philosophy of science and the arguments in the debates in the history of economics points to a kind of unity and continuity in Neurath’s thinking in which specific claims in epistemology and social thought are historically as well as conceptually connected. This unity is moreover an instance of Neurath’s persistent views: his pragmatic and conventionalist epistemology and his view of the unity of science.

The historical and conceptual link is suggested by two elements that appear in Neurath’s arguments. One is the notion of control, the other is the reference to the scenario illustrated by the fiction of Robinson Crusoe. They are both a common feature of discussions of central planning. In Neurath’s writings on that subject they appear together at least once, in 1935 in his essay ‘What is Meant by a Rational Economic Theory?’ There, Neurath protests that

’quite a few political economists advocate the thesis that a Robinson Crusoe—or what amounts to the same thing, a controlled economy—calculates in terms of profits and losses.’ (Neurath 1935/1987, 95)

The two references appear also in the formulations of his private language argument, this time with epistemological meaning. A reference to controlling and an indirect mention of Crusoe appear in 1931 in his essay ‘Physicalism’ and an explicit reference to Crusoe appears in 1932 in ‘On Protocol Statements’. Thus in ‘Physicalism’ Neurath put the argument as follows:

Carnap…distinguished two languages: a ‘monologizing’ one (phenomenalist) and an ‘intersubjective’ (physicalist) one. (…) only one language comes into question from the start, and that is the physicalist. One can learn the physicalist language from earliest childhood. If someone makes predictions and wants to check them himself, he must count on changes in the system of his senses, he must use clocks and rulers, in short, the person supposedly in isolation already makes use of the ‘intersensual’ and ‘intersubjective’ language. The forecaster of yesterday and the controller of today are, so to speak, two persons. (Neurath 1931/1983, 54–55)

In ‘On Protocol Statements’ Neurath refers to Robinson Crusoe explicitly:

The universal jargon…is the same for the child and for the adult. It is the same for a Robinson Crusoe as for a human society. If Robinson wants to join what is in a protocol of yesterday with what is in his protocol today, that is, if he wants to make use of language at all, he must make use of the ‘intersubjective’ language. The Robinson of yesterday and the Robinson of today stand precisely in the same relation in which Robinson stands to Friday…In other words, every language as such is intersubjective. (Neurath 1932b/1983, 96)

Objectivity features prominently in the private language argument. Both Neurath’s argument and Wittgenstein’s earlier one are laid out for the case of an individual epistemic agent understanding himself before he needs to understand others (Uebel 1995b). For both, the constancy and consistency of language use is paramount. It can only be ensured by an intersubjective, that is, objective and social, language, namely the language of physicalism, about ‘spatio-temporal structures’. For Wittgenstein, especially in the Philosophical Investigations, the social dimension of language is a key element of its extrinsic character and therefore its proper justification, the normative condition of possibility and intelligibility of success, and likewise for the more general case of rule-following. The scope of Neurath’s argument is more particularly directed to the case of scientific language in the scientific community.

The notion of private language argument is typically associated with the later argument by Wittgenstein in Philosophical Investigations to the effect that a private language is logically impossible for an individual to use consistently and for others to understand. By private language, Wittgenstein means a language with words whose meaning is essentially constituted by and for the inner experience or individual consciousness of a subject. In a previous version from 1929 (see the Bergen electronic edition), Wittgenstein refers to the primacy of our public everyday language about physical things over a language of immediate sensations. In the 1951 version (2009, 203, 242ff) such language is impossible to coherently make sense of, the language is being shown to be dependent on the public social institutions of language-games and their rules as embedded in actual forms of life. A private language would be a language which could be generated wholly through individual acts of unsharable self-consciousness and understood, in principle, only by that individual speaker, by means of his or her self-consciousness. This is an incoherent notion.

To follow a rule privately means to assume that thinking that one is following a rule is the same as following it (Philosophical Investigations, art. 202). But this assumption is based on a subjective internal notion of justification, dependent on intrinsic individual consciousness. And this is incorrect. For according to Wittgenstein ‘justification consists in appealing to something independent’ (ibid., art. 265). The independence is provided by a notion of language use and rule following with reference, actual or potential, to membership in a wider external community and to intersubjective, that is, public and social, interaction.

For Wittgenstein as well the external, pragmatic and independent notion of calculation and rule following applies to the circulation of money as economic practice. In Wittgenstein’s own words:

Why can’t the right hand give my left hand money? My right hand can put it into my left hand. My right hand can write a deed of gift and my left hand a receipt. But the further practical consequences would not be those of a gift. When the left hand has taken money from the right, etc., we shall ask, “Well, what of it?” (ibid., art. 268)

This intersubjective or objective constraint provides a normative, even if conventional, distinction between consistent and inconsistent language use, or between correct and incorrect rule following. Kripke and David Bloor correctly point out that this condition is not incompatible with Robinson Crusoe’s physical isolation (Kripke 1989, 112, n. 89; Bloor 1997). Now we can see the point of Kripke’s analogy between the impossibility of a private language and the impossibility of central planning. If, as in Mises’s argument, an economic agent has no extrinsic range of intersubjective and commensurable values—that is, the numerical market prices which are set independently by others—, then he has no rational and objective justification for choosing between alternative courses of action. Here exact numerical commensurability and explicit calculation rules are the basis for both objectivity and rationality. In contrast with Kripke’s analogy there is a strong opposing analogy between Neurath’s argument against private language and his defense of central planning. The analogy, as explained in connection with Neurath’s position towards Mises, above, reveals a common set of values that are coherent yet different from the ones involved in Mises’s argument.

The issue of the connection between social models of society and scientific methodology might have been encouraged by the social and political turmoils of the first half of the twentieth century. Neurath’s case was not unique. The issue persists in the works of Neurath’s contemporaries, the philosophers of science Michael Polanyi (1958) and Karl Popper (1950, 1957). Their epistemology of science is also radically social and linked to political and economic thought. A recurring thought experiment that provides guidance through these discussions is the story of Robinson Crusoe.

3. Neurath’s place in logical empiricism: physicalism, anti-foundationalism, holism, naturalism, externalism, pragmatism

3.1 On Language

Neurath’s later views on the language and method of science expressed his simultaneous response to problems in the social sciences and to philosophical issues addressed by the Vienna Circle between 1928 and 1934 and by Karl Popper. A primary aim of the Vienna Circle was to account for the objectivity and intelligibility of scientific method and concepts. Their philosophical approach was to adopt what the Circle member Gustav Bergmann called the linguistic turn, namely, to investigate the formal or structural, logical and linguistic framework of scientific knowledge. The formal approach encompassed logicism and logical analysis as views about the formation and justification of theoretical statements. The problem of empiricism became then the problem of coordination between the formal theoretical structures and the records of observations in such a way that it also offered an explication of how scientific knowledge can be formally constructed (especially logic and mathematics), empirically grounded (except logic and mathematics), rational and objective.

Besides his own early interest in logic and classical and ancient languages, the value of attention to language was familiar to Neurath from the Austrian fin-de-siècle culture of critique of language (Janik and Toulmin 1973), his interest (and his first wife’s) in literature, especially in Goethe (Zemplen 2006, see above), the internationalist and utopianists efforts at introducing new universal languages such as Volapük and Esperanto, the emphasis on signs and universal languages – to be known as pasigraphy – in the scholastic and rationalist philosophical traditions, in the traditions of empirical taxonomies and in the interest in universal language as instrument of knowledge and social order in the Enlightenment, a semiotic tradition in scientific epistemology including Helmholtz, Mach, Duhem and Peirce (Cat 2019) and the sociologist Ferdinand Tönnies’s formal approach to sociology and social signs (Tönnies 1899–1900 and Cartwright et al. 1996, 121–24). The significance of the internationalist and philosophical projects of pasigraphy were acknowledged also by Carnap. More “scientific” sources were recent technical developments in logic, philosophy of science and the foundation of mathematics often claiming Leibniz as a precursor (Leibniz’s logic and project of a universal characteristic had become widely recognized by the late nineteenth century (Peckhaus 2012)). Leading figures in such developments were Frege, Hilbert, Whitehead, Russell and Wittgenstein.

David Hilbert placed the axiomatic tradition in mathematics on a formalist footing by eliminating the requirement of a fixed meaning for primitive terms such as ’points’ and ’lines’ except holistically and implicitly, in the set of axioms or definitions in which they appear. Hilbert extended the application of his program of axiomatics from geometry and arithmetic to physics. Gottlob Frege, followed by N.A. Whitehead and Bertrand Russell, sought to place mathematics, or at least arithmetic, on firm and rational principles of logic, which now included a theory of relations and was to provide a comprehensive and unifying foundation. The reductionist ideal was fatally criticized by Kurt Gödel. Russell, having replaced idealist monism with perceptual atomism, next put the new logical framework to epistemological use in the scientific program of logical construction of objects of experience and thought. His student Wittgenstein, in turn, introduced a linguistic philosophy that limited the world to the scope of the application of an ideal symbolic languages, or calculus. As a result, the sole task of philosophy was, according to Wittgenstein, the critique of language in the form of an activity of clarification, without yielding a distinctive philosophical body of knowledge or set of propositions.

Looking to the rationalist traditions of Descartes and Leibniz, Jan van Heijenoort and Jaako Hintikka have distinguished between two views of language that are relevant to the new linguistic turn (Mormann 1999): language as calculus (LC) and language as universal medium (LUM). The LC tradition, illustrated by Tarski’s views, aligned itself with the Cartesian ideal of a transparent language, with clear and distinctive meaning and explicit, mechanical combination and rule-following that extended to its use in reasoning. There are many possible constructed languages and each is an interpreted calculus with different possible semantics. The LUM tradition adopted the idea of a single actual or ideal language and one semantic or interpretation, to be elucidated, with no possibility of representing its relation to the world from outside. Views by Frege, who pointed to Leibniz on language and reasoning, and Wittgenstein illustrate this tradition, which in turn accommodates two versions, a Cartesian one (Frege and Russell) and a non-Cartesian one (Wittgenstein). Carnap’s conversion to semantics in the early 1930s took him to the LC Cartesian tradition seeking a universal language of rational reconstruction he had previously recognized in the language of physics. Neurath, by contrast, modeled his unification of the sciences in the LUM tradition, on a universal mixed language he called a universal jargon, with descriptions of spatio-temporal arrangements and connections he called physicalism, historically contingent use of vague and ordinary terms (see below). In this context Neurath adopted a militant syntacticism that opposed Carnap’s defense of semantics as metaphysical (Anderson 2019) and engaged in heated terminological disputes that ignored Carnap’s commitment to ontological neutrality (Carus 2019).

The Circle’s projects shared the aforementioned focus on language and experience. The ‘linguistic turn’, as it is known, was adopted as a philosophical tool in order to explicate the rationality and the objectivity—that is, inter-subjectivity—and communicability of thought. Lacking the transcendental dimension of Kant’s metaphysical apparatus, attention to language extended to non-scientific cases such as ‘ordinary language philosophy’ in Oxford. In the context of logical empiricism, the formal dimension of knowledge was thought to be manifest particularly in the exactness of scientific statements. For Schlick, knowledge proper, whether of experience or transcendent reality, was such only by virtue of form or structure—‘only structure is knowable’. For Carnap, in addition, the formal dimension possessed distinct methodological values: it served the purpose of logical analysis and rational reconstruction of knowledge and helped expose and circumvent ‘pseudo-philosophical’ problems around metaphysical questions about reality (his objections to Heidegger appealed to failures of proper logical formulation and not just empirical verification). In 1934 he proposed as the task of philosophy the metalinguistic analysis of logical and linguistic features of scientific method and knowledge (the ‘thesis of metalogic’). For Neurath, this approach helped purge philosophy of deleterious metaphysical nonsense and dogmatism, and acknowledged the radically social nature of language and science.

3.2 From language to logic and its broader relevance

Neurath enjoyed early attention and recognition for his logic work also reflected in early reminiscences of figures such as Popper and the mathematician Karl Menger. Perhaps now surprisingly, mentions of Neurath’s and Olga Hahn’s papers, including a joint one, were included by the logicians C.I. Lewis, in 1918, and Alonzo Church, in 1936, in their canonical bibliographies on symbolic logic (Lewis 1918 and Church 1936).Neurath kept algebraic logic and its symbolic dimension as a recurrent standard and resource, first in his earlier work on the social sciences and pictorial language, and subsequently in related contributions to the discussions that informed logical empiricism (for a detailed discussion, see Cat 2019). The relevance to his interest in political economy concerned the rational and scientific character of economic theory, the possibility of qualitative measurement and the limits of quantification and univocal determination, and, as a result, also of decision-making and prediction. Contrary to predominant accounts using attention to formal languages and logic to pit against each other wings and members of the logical empiricist movement, the symbolic logical standard may be considered a unifying framework that distinguished Neurath with it and not from it. It a unifying reference he willingly adopted when he coined the term ’logical empiricism’ (Mormann 1999 and Cat 2019). The differentiating role in Neurath’s positions can be identified in his shifting and progressively skeptical and critical attention to the standard and the his attention to algebraic logic rather than the newer logic familiar to Carnap at work in Frege and Russell’s logicism.

Leibniz had given modern philosophical currency to the pasigraphic notion of a universal characteristic or Alphabet of Thought that both expressed reality and operated as a logical calculus of reasoning. In the Cartesian spirit, language and reason were inseparable instruments of knowledge and mathematical, logical and philosophical methods were identical. In the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth, Leibniz’s project became a common reference in works in mathematical logic. Not only did Frege see his philosophy of language and mathematical logic within this tradition, as did Peano; Russell penned a landmark study and logicians such as Ernst Schröder and Louis Couturat associated it distinctively with the development of algebraic logic since Boole, especially with Schröder’s own (Peckhaus 2012 and Cat 2019). In this tradition the logician and political economist Stanley Jevons recovered the combinatorial element in Leibniz’s method.

Neurath’s logic writings focused on Schröder’s axiomatic systematization of algebraic logic, mainly in the monumental Vorlesungen über die Algebra der Logik (exakte Logik) (1890-95). There and in earlier writings, Schröder geve a fundamental role to the relation of subsumption and a law of duality. Subsumption was a part-whole relation defined over domains of objects and it was expressed with a symbol, €, which denoted both inclusion and equality (with a corresponding algebraic expression, following Hermann Grassmann, in terms of partial inequality ≤) so that if a € b and b € a, then a=b. The law of duality established a systematic correspondence between theorems in terms of 1 and operation + and theorems in terms of 0 and operation x. The methodological role of duality organizing and deriving theorems was expressed in a dual-column presentation. The latter was adopted in a more general spirit by Neurath and subsequently also by Carnap in his presentation of the systematic correspondence between formal and material modes (see Cat 2019).

By the late nineteenth century, in Austria as well as Germany, algebraic logic had found a central place in the raging controversies over the relationship between science and philosophy and, in particular, between mathematics, logic and psychology. Neurath and Olga Hahn became acquainted with algebraic logic at the University of Vienna sometime around 1902-3, but it wasn’t until 1909, after Olga had become blind and Neurath was back in Vienna providing assistance, that she started working on algebraic logic for her doctorate in philosophy. In 1909 Wilhelm Wundt had published a third volume of his Logik; in 1909, part 1 of Schröder’s synthetic treatment, Abriss der Algebra der Logik appeared posthumously; and in 1910 part 2 was published, as well as Olha Hahn’s thesis director Adolph Stöhr’s Lehrbuch der Logik in Psychologisiender Darstellung (see Cat 2019 for details and references).

Neurath published four papers, one with Hahn (Neurath 1909a, 1909b and 1910a, and Hahn and Neurath 1909). Hahn separately published two others, the second submitted as her doctoral thesis (Hahn 1909 and 1910).In the joint paper, Hahn and Neurath proved the dependence of the principle of duality on the algebraic complementarity of domains of objects to which symbols and operations are applied. Neurath’s own three papers addressed mainly Schröder’s symbolic relation of equality and the property of commutativity of operations sum and product over symbols standing for classes of objects. It included a classification of applications of symbolic equalities and a discussion of univocality, or determinateness, noting its fundamental role in Schröder’s system and following the positivist philosopher Joseph Petzoldt’s discussion of causality, determinism and the interpretation of equality signs in mathematical equations. Neurath distinguished between (quantitative) equality, definitional equality and symbolic equality (Neurath 1910a). with the notational dimension of the latter equality and the lack of cognitive significance Neurath associated with differences in symbolic expression, his linguistic perspective differed markedly from Frege’s. Besides attention to the relativity of notational convention, the significance of the commutation law was, according to Neurath, relative to the axiomatic system (echoing Poincaré’s conventionalist treatment of geometry).

The issues Neurath addressed resonated with ongoing philosophical debates over equality in mathematical equations, identity, definitions, analyticity, axiomatization and conceptual analysis. In addition to the theme of univocality, a second enduring theme that appeared first in the logic writings was the semiotic, or notational, and typographic approach to the conventional introduction and organization of symbols, especially the linear, one-dimensional character of typographic arrangements. The ideas and perspectives he developed in the logic writings played a role in his subsequent discussions of economics, decision-making, scientific theorizing through combinatorial classifications and the epistemological and methodological contributions to logical empiricism.

For instance, he cast the scientific character of political economy in terms of a modal criterion according to which true science consists in systematically examining all possible cases and historical methods provided a laboratory for the exploration of such possibilities (Neurath 1910b, 277). Moreover, this scientific character was also expressed by the aims of systematicity, rationality and exactness, but not quantitative measurability. Exact relations, he declared, were possible between non-measurable quantities. Such qualitative measurements involved logical (and topological) relations such as the ordinal standard based on the algebraic relation of inequality (ibid.). Poincaré had introduced the same ordering relations between ’non-measurable quantities’ such as Gustav Fechner’s psycho-physical sensations to draw attention to the gap between the phenomenological and mathematical ideas of the spatial continuum (Poincaré 1906, 28; Turk 2018). Neurath, following also Poincaré and Fechner by analogy with the case of subjective utility measures, applied this approach to study of the limitations in the method of determination of decisions over collective distributions of satisfaction based on aggregations of individual attributions (Uebel 2004, 37 and Turk 2018, 136). Comparisons between individual pleasure attributions for the same individual or the same object did not determine the comparative order between aggregations: for individuals a and b and objects a and b, we may have determined (Aa)>(Ab) and (Ba)>(Bb), and yet, (Aa)+(Bb)?(Ab)+(Ba) (Neurath 1912/1973, 115). Methodological and epistemological consequences for the formulation of logical empiricist included acknowledging the technical formal contributions to modern science protecting it from metaphysics and meaninglessness, a role captured by the term ’logical empiricism,’ while acknowledging only a limited value for the empirical application formal logical standard (with the risk of pseudorationalism), defending syntacticism about language and unification only through a universal mixed jargon and local logical systematization.

3.3 Scientific and linguistic epistemology

Kant had delivered the latest grand attempt to address the relation between science and philosophy, by taking the former to provide objective empirical knowledge (exact, universal and necessary) and giving to the latter knowledge the task of laying out the conditions of intelligibility and possibility of such knowledge as the sole, critical scope of metaphysics and legitimate exercise of reason. Kant’s standard of a priori, an expression of rationality, was challenged and relativized by the Frege, Russell and Whitehead’s notions of mathematical numbers grounded in logic and by the new notions of space and time in Einstein’s relativity theories. Neither mathematics was synthetic, nor physics seemed a priori; and the synthetic a priori was dismissed as empty of content in the new scientific landscape.

With the scientific world-conception, logical empiricists followed in the footsteps and Helmholtz and Mach and considered a new post-Kantian problematic: investigating the possibility of objective empirical knowledge with a role for intellectual construction without universality or necessity, neither Kantian apriorism nor radical positivism. Logic, with scientific status linked to technical symbolism and the possibility of mathematics, was the sole last refuge for philosophy. The new problematic suggested a demarcation project with two inseparable tasks that were both descriptive and normative: a positive, unifying task to establish and promote the marks of scientific knowledge and the negative task to distinguish it from philosophy.

The a priori kind of knowledge claims expressed in exact theory was circumscribed to the analytic, voided of universality and necessity and deflated by Schlick and Reichenbach to the character of definitions and conventions (following Poincaré). The synthetic kind of knowledge claim was exclusively a posteriori, grounded in experience. The dominating, and later popularized, position was that revisable theoretical scientific statements should stand in appropriate logical relations to unrevisable statements about elementary observations (data), called ‘control sentences’ or ‘protocol sentences’. Such relations would provide theoretical terms with cognitive meaning or sense, and theoretical statements with verification. The form, role and status of protocol statements thus became the topic of an important philosophical debate in the early 1930s involving logical-empiricist philosophers such as Carnap, Moritz Schlick, Edgar Zilsel and Otto Neurath, and others such as Karl Popper. At stake in the debate was precisely the very articulation of a philosophy of scientific knowledge, hence its importance and also the diversity of positions that animated it.

The philosophical discussion that developed around the members of the Vienna Circle was associated with the formulation of logical empiricism and the banner of ‘unity of science against metaphysics’, but it cannot be adequately understood without taking into account the diversity of evolving projects it accommodated. Carnap (much influenced by the neo-Kantian tradition, Einstein’s theories of relativity, Husserl’s phenomenology, Frege’s logic and, i.e., Hilbertian axiomatic approach to mathematics as well as Russell’s own logicism and his philosophical project of logical constructions) was concerned with the conditions of the possibility of objective knowledge, which he considered especially manifest in the formal exactness of scientific claims (Carnap 1928). Schlick (inspired by turn-of-the-century French conventionalists such as Rey, Duhem and Poincaré, Wittgenstein’s philosophy of representation of facts, as well as Einstein’s relativity theories and Hilbert’s implicit definitions and axiomatic approach to mathematics) was interested in the meaning of terms in which actual scientific knowledge of reality is expressed, as well as its foundation on true and certain beliefs about reality (Schlick 1918, 1934). Neurath (influenced by Mach, varieties of French conventionalism, especially Duhem’s, and Marxism) sought to explore the empirical and historical conditions of scientific practice in both the natural and social sciences (Neurath 1931/1973, 1932a/1983). Outside the Vienna Circle, Popper (influenced by Hume, Kant and Austrian child psychology) was interested in addressing the logical and normative issues of justification and demarcation of objective and empirical scientific knowledge, without relying on descriptive discussions of the psychology of subjective experience and meaning (Popper 1935/1951).

The linguistic turn framed the examination of the controversial role of experience. In that respect the discussions of protocol sentences, the so-called protocol sentence debate, addressed their linguistic characteristics and their epistemological status (Uebel 1992). It was another dimension of their examination of both the source of human knowledge and the rejection of metaphysics as nonsense—often dangerous nonsense (Carnap, Hahn and Neurath 1929/1973, and Stadler 2007).

In his classic work Der Logische Aufbau der Welt (1928) (known as the Aufbau and translated as The Logical Structure of the World), Carnap investigated the logical ‘construction’ of objects of inter-subjective knowledge out of the simplest starting point or basic types of fundamental entities (Russell had urged in his late solution to the problem of the external world to substitute logical constructions for inferred entities). He introduced several possible domains of objects, one of which being the psychological objects of private sense experience—analysed as ‘elementary experiences’. These provided the simplest but also the ‘natural starting point in the epistemic order of objects’. This specific construction captures the fact that knowledge is someone’s private knowledge, while it raises Carnap’s (and Kant’s) main problem, namely, how then objective knowledge is possible. In the Aufbau and especially in Pseudoproblems in Philosophy, also here the inclusion of terms and statements in the system of science by this method was intended to exclude all nonsensical speculative statements. It provided a verification criterion not only of testing but also of cognitive significance, or meaning. Carnap stated in that vein that ‘science is a system of statements based on direct experience’ (Carnap 1932/1934).

In spite of the range of alternatives considered, the Aufbau’s main focus on an empiricist, or phenomenological, model of knowledge in terms of the immediate experiential basis was quickly understood by fellow members of the Vienna Circle as manifesting three philosophical positions: reductionism, atomism and foundationalism. Reductionism took one set of terms to be fundamental or primitive; the rest would be logically connected to them. The objectivity, rationality and empirical content and justification of scientific knowledge depended on the resulting vertical integration. Atomism, especially in Neurath’s reading, was manifest semantically and syntactically: semantically, in the analyzability of a term; syntactically or structurally, in the elementary structure of protocols in terms of a single experiential term—‘red circle here now’—; it also appeared in the possibility of an individual testing relation of a theoretical statement to one of more experiential statements. Note that this version of atomism differs from the atomistic positivism about the form of elementary experience that Carnap attributed to Mach, in contrast with his own, scientifically updated and preferred Gestalt-doctrine of a unified field of experience at a given time. The ‘atomic’ concepts of the experiential basis are the result of a ‘quasi-analysis’.

Foundationalism, in the Cartesian tradition of secure basis, took the beliefs in these terms held by the subject to be infallible, or not requiring verification, as well as the sole empirical source of epistemic warrant—or credibility—for all other beliefs. Descartes’s foundationalism is based on a priori knowledge; Carnap’s presentation of the empirical basis instantiates a more modest version. Still a controversial issue among Carnap scholars, Carnap’s kind of foundationalism would be characterized within one structure as a relation to its basis rather than foundationalism, as in Hume or Descartes, regarding one privileged basis over others. In 1932 Carnap acknowledged that he had adopted a ‘refined form of absolutism of the ur-sentence (“elementary sentence”, “atomic sentence”)’ (1932/1987, 469).

Neurath first confronted Carnap on yet another alleged feature of his system, namely, subjectivism. He immediately rejected Carnap’s proposals on the grounds that if the language and the system of statements that constitute scientific knowledge are intersubjective, then phenomenalist talk of immediate subjective, private experiences should have no place. More generally, Neurath offered a private language argument to the effect that languages are necessarily intersubjective. In order to use experience reports to test and verify even one individual’s own beliefs over time, private instantaneous statements of the form ‘red here now’ will not do. To replace Carnap’s phenomenalist language Neurath introduced in 1931 the language of physicalism (Neurath 1931/1983 and 1932a/1983). This is the controversial Thesis of Physicalism: the unity, intelligibility and objectivity of science rests on statements in a language of public things, events and processes in space and time —including behavior and physiological events, hence not necessarily in the technical terms of physical theory. While inspired by materialism, for Neurath this was a methodological and linguistic rule, and not an ontological thesis. (As is the case in Carnap’s methodological solipsism, given Neurath’s anti-metaphysical attitude it would not have been meant as an expression of an objectivist metaphysics in the form of either materialism or social idealism). That physicalism was to avoid metaphysical connotations can be seen further in that, in the spirit of Carnap’s Thesis of Metalogic, its linguistic nature was also central to its applications:

statements are compared with statements, certainly not with some “reality”, nor with “things”, as the Vienna Circle also thought up until now. (Neurath 1931/1983, 53)

Following Neurath, Carnap explicitly opposed to the language of experience a narrower conception of intersubjective physicalist language which was to be found in the exact quantitative determination of physics-language realized in the readings of measurement instruments. Remember that for Carnap only the structural or formal features, in this case, of exact mathematical relations (manifested in the topological and metric characteristics of scales), can guarantee objectivity. Now the unity, objectivity and cognitive significance of science rested on the universal possibility of the translation of any scientific statement into physical language—which in the long run might lead to the reduction of all scientific knowledge to the laws and concepts of physics.

Neurath responded with a new doctrine of protocol statements that considered their distinctive linguistic form, contents and methodological status (Neurath 1932b/1983). This doctrine was meant to explicate the idea of scientific evidence in the framework of empiricism, and it did so by specifying conditions of acceptance of a statement as empirical scientific evidence. It was meant also to circumvent the pitfalls of the alleged subjectivism, atomism, reductionism and foundationalism attributed to Carnap’s earlier discussion of the experiential constitution, or construction system of concepts and knowledge. Neurath’s informal but paradigmatic example of a protocol was:

Otto’s protocol at 3:17 o’clock: [Otto’s speech-thinking at 3:16 was: (at 3:15 o’clock there was a table in the room perceived by Otto)].

Far from Carnap’s atomic sort of protocol statements, Neurath’s model manifested a distinctive complexity of terms and structure (“aggregations”). The protocol contains a factual physicalist core in terms about the table and its location. It also contains the experiential term that provides the linguistic recording of the empirical character of protocols, that is, their experiential origin. Neurath was mindful to caution here that perception terms only admitted physicalistic meaning in terms, for instance, of physiological mechanisms of perception. It also contains the declarative level, marked with ‘Otto says’, which distinguishes the protocol as a linguistic statement. Neurath insisted, again, that the statement had a dual nature, linguistic (propositional and communicative) and physicalist in the form of a physical and physiological process. Finally, the other distinctive elements were the name of the protocolist and the times and locations of the experience and the reports, which provided an intersubjective , physicalist, public alternative to Carnap’s subjective ‘I see a red circle here now’. (Note, however, that for Carnap, the idea of self itself is a constituted concept.)

The general attention to language turned the project of logical empiricism into the problem of the acceptable universal language. Science must be characterized by its proper scientific language. Neurath’s plan was for a unified science against metaphysics, and this involved a plan to police the proper unifying, metaphysics-free language. The negative track of the plan was effectively carried out by the development and adoption of a list of ‘dangerous terms’, which he sometimes referred to, semi-jokingly, as an index verborum prohibitorum: a list of forbidden terms such as ‘I’, ‘ego’, ‘substance’, etc. (Neurath 1933, Neurath 1940/1984, 217). The positive track was the adoption of the universal language of physicalism: ‘metaphysical terms divide—scientific terms unite’ (1935, 23, orig. ital.).

Unlike Carnap’s ideal of basic statement, whether protocol or physicalist, Neurath’s protocols were not ‘clean’, precise or pure in their terms. For Neurath physicalist language, and hence science in turn, is inseparable from ordinary language of any time and place. In particular, it is muddled with imprecise, unanalyzed, cluster-like terms (Ballungen) that appear especially in the protocols: the name of the protocolist, ‘seeing’, ‘microscope’, etc. They were often to be further analyzed into more precise terms or mathematical co-ordinations, but they often would not be eliminated. Even the empirical character of protocol statements could not be pure and primitive, as physicalism allowed the introduction of theoretical—non-perception—terms. Carnap himself, in The Logical Syntax of Language (1934), declared the distinction between analytic and synthetic (protocol-based) statements arbitrary. Physicalism, and thus unified science, were based on a universal ‘jargon’.

The empirical genealogy expressed by protocols was the linguistic expression of empiricism that identified protocol statements as epistemological special units in the system of statements that would constitute objective scientific knowledge. This was Neurath’s attempt to express the empiricist sentiment also behind Carnap’s appeal to experience. A difference from Carnap’s model of protocol appears in the second aspect of their empiricist character, their testing function.

Neurath’s protocols didn’t have the atomic structure and the atomic testing role of Carnap’s. Their methodological role reflected Duhem’s holism: hypotheses are not tested individually; only clusters of statements confront empirical data. But their methodological value in the testing of other statements didn’t make them unrevisable. This is Neurath’s anti-foundationalism: Insofar as they were genuinely scientific statements, consistency with the spirit that opposed science to dogmatic speculation and, no less importantly, opposed naturalistic attention to actual practice, required that protocols too be testable. This is the so-called Neurath Principle: in the face of conflict between a protocol and theoretical statements, the cancellation of a protocol statement is a methodological possibility as well (Neurath 1932/1983, 95, Haller 1982). The role of indeterminacy in the protocol language points to a distinction between a special Neurath Principle and a general Neurath Principle (Cartwright et al. 1996, 202–6). In the former, and earlier, Neurath assumed a determinate logical relation of inconsistency. In the latter, subsequent version, the scope of relations between hypotheses and protocol statements extended to indeterminate relations such that the principle behind the epistemic status of protocol statements is simply grounded on the voluntarisitic and conventionalist doctrine that ‘[a]ll content statements of science, and also their protocol statements that are used for verification, are selected on the basis of decisions and can be altered in principle’ (Neurath 1934/1983, 102). Carnap adopted a similar conventionalist and pragmatic attitude in ‘On Protocol Sentences’ (1932/1987) and in Logical Syntax (1934). The complex structure of the explicitly laid out protocol would serve, in the holistic Duhemian spirit, the purpose of testing it by making explicit as many circumstances as possible which are relevant to the experience, especially as sources of its fallibility (was Otto hallucinating? were all the parts of the experimental instrument working reliably? etc.). Neurath’s dictum was meant to do justice to actual scientific practice with regard to the role of experimental data.

This problematic was only made more challenging by the presence of Ballung-type terms. The method of testing could not be carried out in a logically precise, determinate and conclusive manner, expecting calculability, determinism, omniscience and certainty, as the prevailing ideal of rationality required (Neurath 1913/1983, Neurath 1934/1983 and Cat 1995). Protocol sentences, by virtue of perception terms, could provide certain stability in the permanence of information necessary for the generation of new expressions. But methodologically they could only bolster or shake our confidence. To acknowledge these limitations is a mark of proper rationality—which he opposed to pseudorationality. A loose coherentist view of justification and unification is the only logical criterion available: ‘a statement is called correct if it can be incorporated in this totality’ of ‘existing statements that have already been harmonized with each other’ (Neurath 1931/1984, 66). Reasons underdetermine our actions and thus pragmatic extra-logical factors are required to make decisions about what hypotheses to accept. Thinking requires provisional rules, or auxiliary motives, that fix a conclusion by decision (Neurath 1913/1983). Scientific rationality is situated, contextually constrained by, practical rationality. The system of knowledge is constrained by historically, methodologically and theoretically accepted terms and beliefs, with limited stability, and cannot be rebuilt on pure, secure, infallible empirical foundations. This is the anti-Cartesian naturalism, non-foundationalism, fallibilism and holism of Neurath’s model. This is also the basis for its corresponding conventionalist, constructivist normativity (Uebel 1996 and 2007 and Cartwright et al. 1996). Without the conventions there is no possibility of rationality or objectivity of knowledge. Neurath captured the main features of his doctrine of scientific knowledge in the image of a boat:

There is no way to establish fully secured, neat protocol statements as starting points of the sciences. There is no tabula rasa. We are like sailors who have to rebuild their ship on the open sea, without ever being able to dismantle it in dry-dock and reconstruct it from its best components. Only metaphysics can disappear without a trace. Imprecise ‘verbal clusters’ [Ballungen] are somehow always part of the ship. If imprecision is diminished at one place, it may well re-appear at another place to a stronger degree. (Neurath 1932/1983, 92)

By 1934, the year of the completion of his Logic of Scientific Discovery (Logik der Forschung), Popper had adopted an approach to scientific knowledge based on the logic of method, not on meaning, so that any talk of individual experience would have no linguistic expression (Popper 1935/1951). He unfairly criticized Neurath and also Carnap for allowing with such expressions the introduction of psychologism in a theory of knowledge. For Popper a theory of scientific knowledge was to be not a subjective or descriptive account, but a normative logic of justification and demarcation. He also criticized Neurath’s antifoundationalism about protocols as a form of anti-empiricism that merely opened the door to dogmatism or arbitrariness.

Instead of protocols, Popper proposed to speak about basic statements—a term more attuned to their logical and functional role. They are basic relative to a theory under test. Their empirical character would invisibly reside in the requirement that basic statements be singular existential ones describing material objects in space and time—much like Neurath’s physicalism—which would be observable, in a further unspecified logical not psychological sense. Their components would not themselves be purely empirical terms since many would be understood in terms of dispositional properties, which, in turn, involved reference to law-like generalizations. But their ‘basic’ role was methodological ‘with no direct function of demarcation from metaphysics in terms of meaning, sense or cognitive significance’ and only provisional. They would be brought to methodological use for the purpose of falsifying theories and hypotheses ‘individually and conclusively’ only once they were conventionally and communally accepted by decision in order to stop infinite regress and further theoretical research.

But such acceptance, much as in Neurath’s model, could be in principle revoked. It is a contingent fact that scientists will stop at easily testable statements simply because it will be easier to reach an agreement. It is important that basic statements satisfy explicit conditions of testability or else they could not be rightful part of science. Popper could offer no rational theory of their acceptance on pain of having to have recourse to theories of psychology of perception and thereby weakening his normative criterion of demarcation. In his view, his method, unlike Neurath’s, didn’t lead to either arbitrariness or dogmatism or the abandonment of empiricism. As he had argued against Spengler in 1921, historical contingency provides the rich constraints that establish communities and communication and the possibility of knowledge and, in this holistic form, preclude radical relativism in practice; in historically situated practice, inherited or constructed stable Archimedean points always come into place; there is no tabula rasa (Neurath 1921/1973). Neurath rejected Popper’s approach for its stealth empiricism and its pseudorationalism: its misplaced emphasis on and faith in the normative uniqueness, precision and conclusiveness of a logical method—at the expense of its own limitations and pragmatic character (Zolo 1989, Cat 1995, Hacohen 2000).

Finally, the most radical empiricist attitude toward protocol sentences within the Vienna Circle came from Schlick. Schlick endorsed, following Hilbert, a formal, structural notion of communicable, objective knowledge and meaning as well as a correspondence theory of truth. His realism opposed Neurath’s coherentism, and also the pragmatism and conventionalism of Carnap’s Principle of Tolerance in logical matters as well as his Thesis of Metalogic. But like Carnap’s latter thesis and his syntactic approach of 1934, Schlick was concerned with both the Cartesian ideal of foundational certainty and Wittgenstein’s metalinguistic problem of how language represents the reality it is about; such relation could only be shown, not said. In 1934 Schlick proposed to treat the claims motivating protocol statements, left by Neurath with the status of little more than mere hypotheses, as key to the foundation of knowledge. They would be physicalistic statements that, albeit being fallible, could be subjectively linked to statements about immediate private experiences of reality such as ‘blue here now’ he called affirmations (Konstatierungen) (Schlick 1934). Affirmations carried certainty and elucidated what could be showed but not said, they provided the elusive confrontation or correspondence between theoretical propositions and facts of reality. In this sense they afforded, according to Schlick, the fixed starting points and foundation of all knowledge. But the foundation raised a psychological and semantic problem about the acceptance of a protocol. Affirmations, as acts of verification or giving meaning, lacked logical inferential force; in Schlick’s words, they ‘do not occur within science itself, and can neither be derived from scientific propositions, nor the latter from them’ (Schlick 1934, 95). Schlick’s empiricism regarding the role of protocol sentences suggests but does not support strong epistemological foundationalism. Schlick’s occasional references to a correspondence theory of truth were just as unacceptable and were felt to be even more of a philosophical betrayal within the framework of empiricism. Predictably, Neurath rejected Schlick’s doctrines as metaphysical, manifesting the pseudorationalist attitude (Neurath 1934/1983).

4. Unity of Science and the Encyclopedia Model

Early in his intellectual life, at the turn of the twentieth century, Neurath was acquainted with at least four recent images and projects of unification of the sciences: (1) The scholastic (Llull) and rationalist (Leibniz) tradition of an ideal universal language and calculus of reasoning; (2) the Neo-Kantians’distinction between the Naturwissenschaften and the Geisteswissenschaften; (3) Wundt’s comprehensive logical viewpoints associated with different sciences, or perspectival monism; and (4) the Monist movement more generally, with figures such as Ernst Haeckel and Wilhelm Ostwald that included the project of energetics, with Mach’s related bio-economic, neutral monism of elementary sensations. Subsequently, throughout the 1910s, Neurath engaged four connected debates: (1) The debate over the Neo-Kantian divide between natural and human, or cultural, sciences; (2) the debate over the distinctive role of value judgment in the social sciences; (3) the debate over the scope and validity of concepts and laws in economics; and (4) the debate over the possibility of history as a positive science.

In the Vienna Circle’s manifesto (1929), Neurath ushered in and extolled a scientistic turn in philosophy he labelled the scientific world-conception. Beyond the intellectual, he added, ‘the scientific world-conception serves life and life receives it’ (Carnap, Hahn and Neurath 1929/1973, 306, orig. ital.). Here the project of logical empiricism gets its Enlightenment dimension, with the old reforming, constructive and universalist ambitions, but with new and revised ideas and ideals of society, science and rationality (Uebel 1998). Neurath continued to maintain the view that, as predictive tools, all sciences are ‘aids to creative life’ (Neurath 1931/1973, 319), alongside his view of the complexity of life, e.g., the earthly plane of the empirical world that includes the human, private and social. It cannot surprise, then, that in this new transformative joint philosophical-social project he would urge that ‘the goal ahead is unified science’ (Carnap, Hahn and Neurath 1929/1973, 306, orig. ital.). Like science itself, unified science straddles any divide between theory and action, the world of physical objects and the world of social objectives, past and future, empirical reality and human realization. It is unity of science at the point of action (Cartwright et al 1991, Cartwright et al. 1996 and Cat et al. 1996, O’Neill 2003).

Neurath illustrated the fact that the holistic argument for unification from the complexity of life generalizes Duhem’s holistic argument about prediction and testing with the example of a forest fire:

Certainly, different kinds of laws can be distinguished from each other: for example, chemical, biological or sociological laws; however, it can not be said of a prediction of a concrete individual process that it depend on one definite kind of law only. For example, whether a forest will burn down at a certain location on earth depends as much on the weather as on whether human intervention takes place or not. This intervention, however, can only be predicted if one knows the laws of human behaviour. That is, under certain circumstances, it must be possible to connect all kinds of laws with each other. Therefore all laws, whether chemical, climatological or sociological, must be conceived as parts of a system, namely of unified science. (Neurath 1931/1983, 59, orig. itals.)

Laws of one kind may apply nicely to systems, phenomena or events purely of one kind, but such things are not concrete individuals in the real world. We may think of them as useful models or abstractions; reality behaves more like them only in controlled settings, the outcome of engineering, of planned design and construction, that is, the materialized form of abstraction. Idealizations, like ideal types, dangerously assume real separability between properties (Neurath 1941/1983, 225). In this sense, necessary experimentation for the purpose of prediction and testing that control is key to observation and in turn observation controls theory. In general, from that point of view, exactness and scope requires the possibility of composing models, laws and sciences of different kinds. Science at the point of action is unified science.

Neurath’s philosophical contributions to logical empiricism appear now more distinctly motivated and more clearly understood: It is to serve the valuable goal of unified science, within science, philosophy and society, that Neurath conceived the stress on two further epistemological aims, namely, the role of collective efforts and finally, by implication, intersubjectivity (ibid.). The argument from holism would in turn meet the requirements of the demarcation against metaphysics, since metaphysical terms and metaphysicians divide, whereas scientific terms and scientists unite. The boat images further illustrated Neurath’s aim of unity, within its proper epistemological framework: as a historically situated, non-foundational and collective enterprise. Science is a model and a resource for society and society is in turn a model and resource for science.

In the context and the phase of the rise of logical empiricism, Neurath’s arguments took a general intellectual formulation and application, with references to precedents from intellectual history such as Leibniz and L’Encyclopédie (see SCIENTIFIC UNITY), and an institutional expression in the form of the planned unity of science movement, with its different institutions (Institute of Unified Science), events (International Congresses for the Unity of Science) and publications (International Encyclopedia of Unified Science) (Neurath 1937a/1983, Reisch 1994, Symons et al. 2011).

What are the model and mode of unity? What is the alternative they oppose? Despite popular approaches suggesting a hierarchical, or pyramidal, structure, which he associated with, among others, Comte, Ostwald and then Carnap (in the Aufbau and in his subsequent doctrine of physicalism), Neurath opposed the ideal of ‘pyramidism’ and a ‘system-model’: an axiomatic, precisely and deductively closed and complete hierarchy of conceptually pure, distinct and fixed sciences. He also dismissed the idea of ONE method and ONE ideal language, for instance, mathematics or physics, followed by all the other sciences (Neurath 1936/1983 and Neurath 1937b/1983). Since 1910 Neurath’s approach to the issue was thoroughly antireductionist: cognitively, logically and pragmatically. Each science would fail to deal with the connections to others (Neurath 1910/2004). In particular, electron talk, Neurath insisted, is irrelevant to understanding and predicting the complex behavior of social groups.

The imperative of unity required that ‘it must be possible to connect each law with every other law under certain circumstances, in order to obtain new formulations’ (Neurath 1931/1983, 59). Instead of the system-model, he proposed a weaker, dynamical and local model of integration he called the ‘encyclopedia-model’: a more or less coherent totality of scientific statements at a given time, in flux, incomplete, with linguistic imprecisions and logical indeterminacy and gaps, unified linguistically by the universal jargon of physicalist language (not Carnap’s physicalism)—a mixture of ‘cluster’ and ‘formula’—, the cooperative and empiricist spirit, and the acceptance of a number of methods or techniques (probability, statistics, etc), all providing ‘cross-connections’ (Neurath 1936/1983, 145–158 and 213–229). The evolution of the sciences could be said to proceed from encyclopedias to encyclopedias (a model weaker and more pluralistic than those based on Kuhn’s paradigms and Foucault’s epistèmes, but closer to Carnap’s later notion of linguistic frameworks; from this perspective, it seems less paradoxical that Carnap published Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in the last volume of the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science). Neurath spoke of a ‘mosaic’, an ‘aggregation’, an interdisciplinary ‘orchestration’ of the sciences as ‘systematisation from below’ rather than a ‘system from above’, especially, after World War II, carefully excluding any form of ‘authoritative integration’, even favoring ‘cooperation in fruitful discussion’ to a socialist, Nazi or totalitarian-sounding talk of a ‘programme’ (Neurath 1936/1983 and Neurath 1946/1983, 230–242). Correspondingly, his later political writings emphasized internationalism, democracy and plurality of institutional loyalties.

The disciplinary dismissal of philosophy, especially its talk of transcendental entities that make up metaphysical doctrines, hardly recommend calling Neurath’s views a philosophy. At the same time, his emphasis on science was coached in a framework that connected thought and action. One may speak of a program. Neurath’s program was intended to be and was pluralistic and ‘aggregational’ through and through, semantically, theoretically, disciplinarily, educationally, socially, politically.

5. Philosophy of psychology, education, and the social sciences

5.1 Philosophy of psychology

Vienna became an international capital of psychological research while logical empiricism started to develop a scientific epistemology and an epistemology of science with normative demarcation goals. Freud’s psychoanalysis was more popular than J.B. Watson’s American behaviorism and Gestalt psychology was dominant neither in psychology nor scientific philosophy. The members of the Vienna Circle collectively adopted its framework of scientism and anti-metaphysics, of logic and empiricism, and aimed to select their intellectual allies and targets accordingly. Yet, individually, they tailored their considerations of the different sciences to their respective agendas, shifting projects and development. In the Vienna Circle manifesto, the official programmatic position was to point to the defects of much contemporary psychological language, plagued by metaphysical burden, conceptual imprecision and logical inconsistency. The emphasis on perception selected behaviorist psychology as intellectual ally consistent with the Circle’s scientific world-conception (Carnap, Hahn and Neurath 1929/1973, 314-5, Hardcastle 2007).

Hans Reichenbach, Carnap and Schlick’s ally in Berlin, was the leader of the Berlin Society for Scientific Philosophy, also known as the Berlin Circle, and hence was in personal and intellectual interaction with Wolfgang Köhler in Berlin. Eventually he would mention Gestalt theory in his writings in 1931, in ‘Aims of Modern Philosophy of Nature’. There he raised the question of the philosophical problems of psychology and focused on Gestalt theory as ‘a recent development’ that ‘subsumes psychological events under the concept of Gestalt (…) an organized arrangement of experiences’ (Reichenbach 1931/1959, 88).

Like Kant, Popper was interested in a transcendental and regulative philosophy, and, more so than Kant, he hailed science as the paradigm of intellectual activity. But by 1928 he was still holding a commitment to inductivism. In 1928 Popper finished his doctoral dissertation, ‘On the Methodological Problem of Cognitive Psychology’. There, Popper set out to understand the relations between logic, biology and psychology in the production of knowledge and, to that effect, to outline the methodological preconditions of cognitive psychology. Two alternative views of psychology were available to Popper through his two doctoral examiners, Karl Bühler and Moritz Schlick.

Schlick represented Gestalt theory as psychology within the reductive framework of physicalism, that is, rejecting the existence of autonomous entities, laws and methods of psychology. Bühler’s career was central to Austrian psychology and to Red Vienna culture. After an assistantship with Stumpf in his Berlin’s laboratory, Bühler had emerged, along with Otto Selz and Max Wertheimer, from the research laboratory of Ostwald Külpe in Würtzburg. With Külpe he had engaged in empirical research on thought processes—contra Wundt’s atomistic psychology-, with special attention to imageless thought and the importance of language. He subsequently moved with Külpe to Bonn and eventually replaced him in Munich in 1915. In 1912 Bühler had originally contributed to Gestalt psychology with the discussion of simple Gestalt forms involved in the perception of proportions of geometrical figures and ended concentrating on his cognitive phenomenon of the ‘aha experience’, a sudden insight in problem solving. Interested in the same phenomenon, Charlotte Malachowski was encouraged by Stumpf to join Bühler in Munich, where she became his wife. They collaborated on a project to study the mental development of children, ending with intelligent learning through language. The results appeared in his The Mental Development of the Child (1918), which immediately became the standard reference on the subject.

In Vienna, Otto Glöckel, founder of the world-renowned Vienna School Reform movement and president of the Vienna School Board, offered to fund for the Bühlers a psychological laboratory. After Karl Bühler had lost to Köhler the appointment to the Berlin posts, he ended up assuming in 1923 the directorship of the newly funded Psychological Institute of Vienna. From the Institute the Bühlers became central to Red Vienna culture. They taught at the Pedagogical Academy of Vienna. In addition, she focused on children education and psychological welfare. His interest in language and philosophy brought him closer to Schlick (Wittgenstein’s sister Margaret organized social occasions for Wittgenstein, the Bühlers and the Schlicks to meet) and he encouraged his students to attend Vienna Circle seminars (Egon Brunswick, Elsa Frankel, Marie Jahoda, Paul Lazersfeld, Rudolf Ekstein and Edith Weisskopf). Then in 1927 he published Die Krise der Psychologie (The Crisis of Psychology). In the book, Bühler argued that the problem of explaining the social significance of language showed that psychology has lost the complexity and richness required to synthesize three levels of psychology: experience, behavior and intellectual structure (Bühler 1927, Hacohen 2000 and Humphrey 1951). A framework was needed for unifying the different narrow ‘schools’ of psychology: Behaviorism, Gestalt theory, psychoanalysis, associationism, and humanistic psychology. They were deficient in their narrow domain of application. The unity of psychology demanded methodological pluralism at the point of cooperation.