Trinity

The traditional Christian doctrine of the Trinity is commonly expressed as the statement that the one God exists as or in three equally divine “persons”, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Every significant concept in this statement (God, exists, as or in, equally divine, person) has been variously understood. The guiding principle has been the creedal declaration that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit of the New Testament are consubstantial (i.e. the same in substance or essence, Greek: homoousios). Because this shared substance or essence is a divine one, this is understood to imply that all three named individuals are divine, and equally so. Yet the three in some sense “are” the one God of the Bible.

After its formulation and imperial enforcement towards the end of the fourth century, this sort of Christian theology reigned more or less unchallenged. But before this, and again in post-Reformation modernity, the origin, meaning, and justification of trinitarian doctrine has been repeatedly disputed. These debates are discussed in supplementary documents to this entry. One aspect of these debates concerns the self-consistency of trinitarian theology. If there are three who are equally divine, isn't that to say there are at least three gods? Yet the tradition asserts exactly one God. Is the tradition, then, incoherent, and so self-refuting? Since the revival of analytic philosophy of religion in the 1960s, many Christian philosophers have pursued what is now called analytic theology, in which central religious doctrines are given formulations which are precise, and it is hoped self-consistent and otherwise defensible. This article surveys these recent “rational reconstructions” of the Trinity doctrine, which centrally employ concepts from contemporary analytic metaphysics, logic, and epistemology.

- 1. One-self Theories

- 2. Three-self Theories

- 3. Mysterianism

- Bibliography

- Academic Tools

- Other Internet Resources

- Related Entries

Additional material related to this entry can be found in three supplementary documents:

1. One-self Theories

One-self theories assert the Trinity, despite initial appearances, to contain exactly one self.

1.1 Selves, gods, and modes

A self is being which is in principle capable of knowledge, intentional action, and interpersonal relationships. A god is commonly understood to be a sort of extraordinary self. In the Bible, the god Yahweh (a.k.a. “the LORD”) commands, forgives, controls history, predicts the future, occasionally appears in humanoid form, enters contracts with human beings, and sends prophets, whom he even allows to argue with him. More than a common god in a pantheon of gods, he is portrayed as being the one creator of the cosmos, and as having uniquely great power, knowledge, and goodness.

Trinitarians hold this revelation of the one God as a great self to have been either supplemented or superceded by later revelation which shows the one God in some sense to be three “persons.” (Greek: hypostaseis or prosopa, Latin: personae) But if these divine “persons” are selves, then the claim is that there are three divine selves, which is to say, three gods. Some Trinity theories understand the “persons” to be selves, and then try to show that the falsity of monotheism does not follow. (See section 2 below.) But a rival approach is to explain that these three divine “persons” are really ways the one divine self is, that is say, modes of the one god. In current terms, one reduces all but one of the three or four apparent divine selves (Father, Son, Spirit, the triune God) to the remaining one. One of these four is the one god, and the others are his modes. Because the New Testament seems to portray the Son and Spirit as somehow subordinate to the one God, one-self Trinity theories always either reduce Father, Son, and Spirit to modes of the one, triune God, or reduce the Son and Spirit to modes of the Father, who is supposed to be numerically identical to the one God. (See section 1.6 for views on which only the Holy Spirit is reduced to a mode of God, that is, the Father.)

Because God in the Bible is always portrayed as a great self, at the popular level of trinitarian Christianity one-self thinking has a firm hold. Liturgical statements, song lyrics, and sermons frequently use trinitarian names (“Father”, “Son”, “Jesus”, “God”, etc.) as if they were interchangeable, co-referring terms, referring directly or indirectly (via a mode) to one and the same divine self.

At the level of official doctrine, among large Christian groups, only the theology of the United Pentecostal Church (a.k.a. “Oneness” Pentecostals), is clearly and consistently one-self trinitarian; on “Oneness” theology the Three are either identified with God himself, or with aspects or actions of God. Not recognizing that the trinitarian tradition includes one-self theories, they traditionally reject “the Trinity” (understanding it as positing three divines selves and so not being consistently monotheistic) and define their theology in opposition to it (Bernard 2001, 255–60). Thinkers on both sides periodically argue that trinitarian-Oneness difference are merely verbal, which they may be, if “trinitarian” means a one-self trinitarian.

1.2 What is a mode?

But, what is a “mode”? It is a “way a thing is”, but that might mean several things. A “mode of X” might be

- an intrinsic property of X (e.g., a power of X, an action of X)

- a relation that X bears to some thing or things (e.g., X's loving itself, X's being greater than Y, X appearing wonderful to Y and to Z)

- a state of affairs or event which includes X (e.g., X loving Y, it being the case that X is great)

One-self trinitarians often seem to have in mind the last of these. (E.g., The Son is the event of God's relating to us as friend and savior. Or the Son is the event of God's taking on flesh and living and dying to reveal the Father to humankind. Or the Son is the eternal event or state of affairs of God's living and relating to himself in a son-like way.) If an event is (in the simplest case) a substance (thing) having a property (or a relation) at a time, then the Son (etc.) will be identified with God's having a certain property, or being in a certain relation, at a time (or timelessly). By a natural slide of thought and language, the Son (or Spirit) may just be thought of and spoken of as a certain divine property, rather than God's having of it (e.g., God's wisdom).

Modes may be essential to the thing or not; a mode may be something a thing could exist without, or something which it must always have so long as it exists. (Or on another way to understand the essential/non-essential distinction, a mode may belong to a thing's definition or not.)

There are three ways these modes of a eternal being may be temporally related to one another: maximally overlapping, non-overlapping, or partially overlapping. First, they may be eternally concurrent—such that this being always, or timelessly, has all of them. Second, they may be strictly sequential (non-overlapping): first the being has only one, then only another, then only another. Finally, some of the modes may be had at the same times, partially overlapping in time.

1.3 One-self Theories and “Modalism” in Theology

Influential 20th century theologians Karl Barth (1886–1968) and Karl Rahner (1904–84) endorse one-self Trinity theories, and suggest alternative terms for “person” for what the triune God is three of. They argue that “person” has come in modern times to mean a self. But three divine selves would be three gods. Hence, even if “person” should be retained as traditional, its meaning in the context of the Trinity should be expounded using phrases like “modes of being” (Barth) or “manners of subsisting” (Rahner) (Ovey 2008, 203–13; Rahner 1997, 42–5, 103–15).

In Barth's own summary of his position,

As God is in Himself Father from all eternity, He begets Himself as the Son from all eternity. As He is the Son from all eternity, He is begotten of Himself as the Father from all eternity. In this eternal begetting of Himself and being begotten of Himself, He posits Himself a third time as the Holy Spirit, that is, as the love which unites Him in Himself. (Barth 1956, 1)

All of Barth's capitalized pronouns here refer to one and the same self, the self-revealing God, eternally existing in three ways. Similarly, Rahner says that God

…is – at once and necessarily – the unoriginate who mediates himself to himself (Father), the one who is in truth uttered for himself (Son), and the one who is received and accepted in love for himself (Spirit) – and… as a result of this, he [i.e. God] is the one who can freely communicate himself. (Rahner 1997, 101–2, original emphasis)

In both cases these modes are assumed to be essential and maximally overlapping.

Mainstream Christian theologians nearly always reject “modalism”, meaning a one-self theory like that of Sabellius (fl. 220), an obscure figure who is commonly interpreted as saying that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are sequential, non-essential modes, something like ways God interacts with his creation. Thus, in one epoch, God exists in the mode of Father, during the first century he exists as Son, and then after Christ's resurrection and ascension, he exists as Holy Spirit (Leftow 2004, 327; McGrath 2007, 254–5; Pelikan 1971, 179). Sabellian modalism is usually rejected on the grounds that such modes are strictly sequential, or because they are not intrinsic features of God, or because they are intrinsic but not essential features of God. The first aspect of Sabellian modalism conflicts with episodes in the New Testament where the three appear simultaneously, such as the Baptism of Jesus in Matthew 3:16–7. The last two are widely held to be objectionable because it is held that a doctrine of the Trinity should tell us about how God really is, not merely about how God appears, or because a trinitarian doctrine should express (some of) God's essence. Sabellian and other ancient modalists are sometimes called “monarchians” because they upheld the sole monarchy of the Father, or “patripassians” for their (alleged) acceptance of the view that the Father (and not only the Son) suffered in the life of the man Jesus.

While Sabellian one-self theories were rejected for the reasons above, these reasons don't rule out all one-self Trinity theories, such as ones positing the Three as God's modes in the sense of his eternally having certain intrinsic and essential features. Sometimes the Trinity doctrine is expounded by theologians as meaning just this, the creedal formulas being interpreted as asserting that God (non-contingently) acts as Creator, Redeemer, and Comforter, or describing “God as transcendent abyss, God as particular yet unbounded intelligence, and God as the immanent creative energy of being… three distinct ways of being God”, with the named modes being intrinsic and essential to God, and not mere ways that God appears (Ward 2002, 236; cf. Ward 2000, 90).

1.4 Divine Life Streams

Brian Leftow sets the agenda for his own one-self theory in an attack on “social”, that is, three-self theories. (See section 2 below.) In contrast to these, he asserts that

…there is just one divine being (or substance), God….[As Thomas Aquinas says,] God begotten receives numerically the same nature God begetting has. To make Aquinas' claim perfectly plain, I introduce a technical term, “trope”. Abel and Cain were both human. So they had the same nature, humanity. Yet each also had his own nature, and Cain's humanity was not identical with Abel's… A trope is an individualized case of an attribute. Their bearers individuate tropes: Cain's humanity is distinct from Abel's just because it is Cain's, not Abel's. With this term in hand, I now restate Aquinas' claim: while Father and Son instance the divine nature (deity), they have but one trope of deity between them, which is God's….bearers individuate tropes. If the Father's deity is God's, this is because the Father just is God. (1999, 203–4, original emphasis)

Leftow characterizes his one-self Trinity theory as “Latin”, following the recent practice of contrasting Western or Latin with Eastern or Greek or “social” Trinity theories. Leftow considers his theory to be in the lineage of some prominent Latin-language theorists. (See the supplementary document on the history of trinitarian doctrines, section 3.3.2, on Augustine, and section 4.1, on Thomas Aquinas.)

This sort of one-self theory needn't commit to trope theory about properties. Rather, whether or not properties are tropes,…the Father's having deity = [is numerically or absolutely identical to] the Son's having deity. For both are at bottom just God's having deity. (Leftow 2007, 358, original emphasis)

Leftow makes an extended analogy with time travel; just as a dancer may repeatedly time travel back to the dance stage, resulting in a whole chorus line of dancers, so God may eternally live his life in three “streams” or “strands” (Leftow 2004, 312–23). Each person-constituting “strand” of God's life is supposed to (in some sense) count as a “complete” life (although for any one of the three, there's more to God's life than it) (Leftow 2004, 312). Just as the many stages of the time-traveling dancer's life are united into stages of her by their being causally connected in the right way, so too, analogously, the lives of each of the three persons count as being the “strands of” the life of God, because of the mysterious but somehow causal inter-trinitarian relations (the Father generating Son, and the Father and Son spirating the Spirit) (313–4, cf. 321–2, Leftow 2012a, 313).

It is crucial to understanding Leftow's use of the time travel analogy that in his view time-travel does not require believing that entities are four-dimensional (Leftow 2012b, 337). If a single dancer, then, time travels to the past to dance with herself, this does not amount to one temporal part of her dancing with a different temporal part of her. If that were so, neither dancer would be identical to the (whole, temporally extended) woman. But Leftow supposes that both would be identical to her, and so would not be merely her temporal parts. He holds that if time travel is possible, a self may have multiple instances or iterations at a time. His theory is that the Trinity is like this, subtracting out the time dimension. God, in timeless eternity, lives out three lives, or we might say exists in three aspects. In one he's Father, in another Son, and in another the Holy Spirit. But they are all one self, one God, as it were three times repeated or multiplied.

Leftow argues that his theory isn't any undesirable form of “modalism” (i.e. a heretical one-self theory) because

Nothing in my account of the Trinity precludes saying that the Persons' distinction is an eternal, necessary, non-successive and intrinsic feature of God's life, one which would be there even if there were no creatures. (Leftow 2004, 327)

Leftow wants to show what is wrong with the following argument (2004, 305–6; cf. 2007, 359):

- the Father = God

- the Son = God

- God = God

- the Father = the Son (from 1–3)

- the Father generates the Son

- God generates God (from 1, 2, 5).

His point is that creedal orthodoxy requires 1–3 and 5, yet 1–3 imply the unorthodox 4, and 1, 2 and 5 imply the unorthodox (and necessarily false) statement 6. So what to do? Lines 1–4 seem perfectly clear, and the argument seems valid. So too does the argument from 1, 2, and 5 to 6. Why should 6 be thought impossible? The idea is that whatever its precise meaning, “generation” is some sort of causing or originating, something in principle nothing can do to itself. One would expect Leftow, as a one-self trinitarian, to deny 1 and 2, on the grounds that neither Father nor Son are identical to the one self which is God, but rather, each is a mode of God. But Leftow instead argues that premises 1 and 2 are unclear, and that depending on how they are understood, the argument will either be sound but not heretical, or unsound because it is invalid, 4 not following from 1–3, and 6 not following from 1, 2, and 5.

The argument seems straightforward so long as we read “Father” and “Son” as merely singular referring terms. But Leftow asserts that they are also definite descriptions “which may be temporally rigid or non-rigid” (Leftow 2012b, 334–5). A temporally rigid term refers to a being at all parts of its temporal career. Thus, if “the president of the United States” is temporally rigid, then in the year 2013 we may truly say that “The president of the United States lived in Indonesia”, not of course, while he was president, but it is true of the man who was president in 2013, that in his past, he lived in Indonesia. If the description “president of the United States” (used in 2013) is not temporally rigid, then it refers to Barak Obama only in the presidential phase of his life, and so the sentence above would be false.

“The Father”, then, is a disguised description, something like “the God who is in some life unbegotten” (2012b, 335) (For “the Son” we would substitute “begotten” for the last word.)

Because the “=” sign can have a non-temporally rigid description on one or both sides of it, then there can be “temporary identities”, that is, identity statements which are true only at some times but not others. And then such identity statements can only be true or false relative to times, or to something time-like (Leftow 2004, 324).

If the terms “Father” and “Son” are temporally rigid, or at least like such a term in that each applies to God at all portions of his life (which isn't temporally ordered), then 4 does follow from 1–3. But 4, Leftow argues, is theologically innocuous, as it means something like “the God who is in some life the Father is also the God who is in some life the Son” (2012b, 335). This is “compatible with the lives, and so the Persons, remaining distinct,” seemingly, distinct instances of God (each of which is identical to God), and Leftow accepts 1–4 as sound only if 4 means this (ibid.).

If the terms “Father” and “Son” are temporally non–rigid, or at least like such a term in that each applies to God relative to some one portion of his life but relative to the others, then the argument is unsound. Relative to the Father-strand of God's life, 1 will be true but 2 will be false. Relative to the Son-strand, 2 will be true, but 1 will be false. 3 and 5 will be true relative to any strand, but in any case, we will not be able to establish either 4 or 6.

Leftow's theory crucially depends on modes, that is: intrinsic, essential, eternal ways God is, that is, lives or life-strands. But he does not identify the “persons” of the Trinity with these modes. Rather, he asserts that the modes somehow constitute, cause, or give rise to each “person” (Leftow 2007, 373–5). Like theories that reduce these “persons” to mere modes of a self, Leftow's theory has it that what may appear to be three selves actually turn out to be one self, God. But they, all three of them, just are (are numerically, absolutely identical to) that one self, that is, God thrice over or thrice repeated.

1.5 Difficulties for One-self Theories

Some philosophers object that Leftow's time-travel analogy is unhelpful because time-travel is impossible (Hasker 2009, 158). Similarly, one may object that Leftow is trying to illuminate the obscure (the Trinity) by the equally or more obscure (the alleged possibility of time travel, and timeless analogues to it). If Leftow's one-self theory is intended as a literal interpretation of trinitarian language, a “rational reconstruction” (Tuggy 2011a), this would be problematic; but if he means it merely as an apologetic defense (i.e. we can't rule out that the Trinity means this, and this can't be proven incoherent) then the fact that some intellectuals believe in the possibility of time travel supports his case.

One may wonder whether Leftow's life stream theory is really trinitarian. Do not his “persons” really so to speak collapse into one, since each is numerically identical to God? Again, one may worry that Leftow's concept of God being “repeated” or having multiple instances or iterations is not coherent.

William Hasker objects that assuming Leftow's theory,

In the Gospels, we have the spectacle of God–as–Son praying to himself, namely to God–as–Father. Perhaps most poignant of all… are the words of abandonment on the cross, “My God, why have you forsaken me?” On the view we are considering, this comes out as “Why have I–as–Father forsaken myself–as–Son?” (Hasker 2009, 166, original emphases)

In reply, Leftow argues that if we accept the coherence of time travel stories, we should not be bothered by the prospect of “one person at one point in his life begging the same person at another point” (Leftow 2012a, 321). About the cry of abandonment, Leftow urges that the New Testament reveals a Christ who (although divine and so omniscient) did not have full access to his knowledge, specifically knowledge of his relation to the Father, and so Christ could not have meant what Hasker said above. Instead, he “would have been using the Son's “myself” and “I”, which… pick out only the Son” (Leftow 2012a, 322).

Hasker also objects that Leftow's one–self theory collapses the personal relationships of the members of the Trinity into God's relating to himself, and suggests that in Leftow's view, God would enjoy self–love, but not other–love, and so would not be perfect (Hasker 2009, 161–2; Hasker 2012a, 331). (On this sort of argument see section 2.3 below.) Leftow replies that the self–love in question would be “relevantly like love of someone else” and so, presumably, of equal value (Leftow 2012b, 339).

Finally, does the theory imply “patripassianism”, the traditionally rejected view that the Father suffers? (The Son suffers, and both he and the Father are identical to God.) Leftow argues that nothing heretical follows; if his analysis is right “then claiming that the Father is on the Cross is like claiming that The Newborn [sic] is eligible to to join the AARP [an organization for retirees]”, that is, true but misleading (2012b, 336).

Any one-self theory is hard to square with the New Testament's theme of the mutual love of Father and Son. Any one-self theory is also hard to square with the Son's role as mediator between God and humankind. These teachings arguably assume the Son to be a self, and not a mere mode of a self, and to be a different self than his Father. Theories such as Ward's (section 1.3 above), which make the Son a mere mode, make him not a self at all, whereas Leftow's theory (section 1.4 above) makes him a self, but the same self as his Father. Either way, the Son seems not to be qualified either to mediate between God and humankind, or to be a friend of the one he calls Father.

Again, traditional incarnation theory seems to assume that the eternal Son who becomes incarnate (who enters into a hypostatic union with a complete human nature) is the same self as the historical man Jesus of Nazareth. But no mere mode could be the same self as anything, and the New Testament seems to teach that this man was sent by another self, God.

Some one–self theories run into trouble about God's relation to the cosmos. If God exists necessarily and is essentially the creator and the redeemer of created beings in need of salvation, this implies it is not possible for there to be no creation, or for there to be no fallen creatures; God could not have avoided creating beings in need of redemption. One-self trinitarians may get around this by more carefully specifying the properties in question: not creator but creator of anything else there might be, and not redeemer but redeemer of any creatures in need of salvation there might be and which he should want to save.

1.6 The Holy Spirit as a Mode of God

Most 17th-19th century unitarians, present-day “biblical unitarians”, and some current subordinationists such as the Jehovah's Witnesses hold the Holy Spirit to be a mode of God—God's power, presence, or action in the world. (See the supplementary document on unitarianism.) Not implying modalism about the Son, this position is harder to refute on New Testament grounds, although mainstream theologians and some subordinationist unitarians reject it as inconsistent with New Testament language from which we should infer that the Holy Spirit is a self (Clarke 1738, 147). These groups counter with other biblical language which suggests that the “Spirit of God” or “Holy Spirit” refers to either God himself, a mode of God (e.g., his power), or an effect of a mode of God (e.g., supernatural human abilities such as healing). (See Burnap 1845, 226–52; Lardner 1793, 79–174; Wilson 1846, 325–32.) This exegetical debate is difficult, as all natural languages allow persons to be described in mode-terms (“Hillary is Bill's strength.”) and modes to be described in language which literally applies only to persons. (“God's wisdom told him not to create beer-sap trees.”)

2. Three-self Theories

One-self Trinity theories are motivated by the concern that three divine selves implies three gods. Three-self theories, in various ways, deny this implication. That is, they hold the “persons” of the Trinity to be selves (as defined above, section 1.1).

2.1 Relative Identity Theories

Why can't multiple divine selves be one and the same god? It would seem that by being the same god, they must be numerically the same entity; “they” are really one, and so “they” can't differ in any way (that is, this one entity can't differ from itself). But then, they (it) can't be different divine selves.

Relative identity theorists think there is some mistake in this reasoning, so that things may be different somethings yet the same something else. They hold that the above reasoning falsely assumes something about numerical sameness. They hold that numerical sameness, or identity, either can be or always is relative to a kind or concept.

Again, relative identity theorists are concerned to rebut this sort of argument:

- The Father is God.

- The Son is God.

- Therefore, the Father is the Son.

If each occurrence of “is” here is interpreted as identity (“absolute” or non-relative identity), then this argument is indisputably valid. Things identical to the same thing must also be identical to one another. The relative identity trinitarian argues that one should read the “is” in 1 and 2 as meaning “is the same being as” and the “is” in 3 as meaning “is the same divine person as”. Doing this, one may may say that the argument is invalid, having true premises but a false conclusion. But does this rebuttal work?

Following Rea (2003) we divide relative identity trinitarian theories into the pure and impure.

2.1.1 Pure Relative Identity Theories

Peter Geach (1972, 1973, 1980) argues that it is senseless to ask whether or not some a and b are “the same”; rather, sameness is relative to a sortal concept. Thus, while it is senseless to ask whether or not Paul and Saul are identical, we can ask whether or not Saul and Paul are the same human, same person, same apostle, same animal, etc. The doctrine of the Trinity, then, is construed as the claim that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are the same God, but are not the same person. They are “God-identical but Person-distinct” (Rea 2003, 432). The resulting trinitarian theory avoids the inconsistencies mentioned above. Geach's approach to the Trinity is developed by Martinich (1978, 1979) and Cain (1989).

This sort of relative identity trinitarianism, however, depends on the very controversial claim that there's no such relation as (non-sortal-relative, absolute) identity. Most philosophers hold, to the contrary, that the identity relation and its logic are well-understood. One might turn to a weaker relative identity doctrine; outside the context of the Trinity, philosopher Nicholas Griffin (1977; cf. Rea 2003, 435–6) has argued that while there are identity relations, they are not basic, but must be understood in terms of relative identity relations. On either view, relative identity relations are fundamental.

It has been objected to Geach's claim about the senselessness of asking if a and b are “the same” that,

Given that we have succeeded in picking out something by the use of “a” and in picking out something by the use of “b” it surely is a complete determinate proposition that a = b, that is, it is surely either true or false that the item we have picked out with “a” is the item we have picked out with “b”. (Alston and Bennett 1984, 558)

Rea objects that relative identity theory presupposes some sort of metaphysical anti-realism, the controversial doctrine that there is no realm of real objects which exists independently of human thought (Rea 2003, 435–6).

Trenton Merricks objects that if a and b “are the same F”, this implies that a is an F, that b is an F, and that a and b are (absolutely, non-relatively) identical. But this is precisely what relative identity trinitarians deny, and this denial leads to the resulting relative-identity trinitarian claims being unintelligible (we have no grasp of what they mean). If someone asserts that Fluffy and Spike are “the same dog” and denies that they're both dogs, and that they're one and the same, we have no idea what this person is asserting. Similarly with the claim that Father and Son are “the same God” but are not identical (Merricks 2006, 301–5, 321; cf. Tuggy 2003, 173–4).

One may also object to either theory being an analysis of the historical doctrine, on the grounds that only those conversant in the logic of the last 120 years or so have ever had a concept of relative identity. This may be disputed—Anscombe and Geach (1961, 118) argue that Aquinas should be read along these lines, and Richard Cartwright (1987, 193) claims to find the doctrine in the works of Anselm and in the Eleventh Council of Toledo (675). (See supplementary document on the history of trinitarian doctrines section 4.)

2.1.2 Impure Relative Identity Theories

Peter van Inwagen (1995, 2003) tries to show that there is a set of propositions representing a possibly orthodox interpretation of the “Athanasian” creed which is demonstrably self-consistent, refuting claims that the Trinity doctrine is obviously self-contradictory. He formulates a trinitarian doctrine using a concept of relative identity, without employing the concept of identity or presupposing that there is or isn't such a thing (van Inwagen 1995, 241). Specifically, he proves that the following eight claims (understood as involving relative and never absolute identity, the names being read as descriptions) don't imply a contradiction in relative identity logic.

- There is (exactly) one God.

- There are (exactly) three divine Persons.

- There are three divine Persons in one divine Being.

- God is the same being as the Father.

- God is a person.

- God is the same person as the Father.

- God is the same person as the Son.

- The Son is not the same person as the Father.

- God is the same being as the Father. (249, 254)

Van Inwagen neither endorses this Trinity theory, nor presumes to pronounce it orthodox, and he admits that it does little to reduce the mysteriousness of the traditional language.

It may be objected, as to the preceding theory, that van Inwagen's relative identity trinitarianism is unintelligible. Merricks argues that this problem is more acute for van Inwagen than for Geach, as the former declines to adopt Geach's claim that all assertions of identity, in all domains of discourse, and in everyday life, are sortal-relative (Merricks 2006, 302–4).

Michael Rea (2003) objects that by remaining neutral on the issue of identity, van Inwagen's theory allows that the three persons are (absolutely) non-identical, in which case “it is hard to see what it could possibly mean to say that they are the same being…” (Rea 2003, 441) It seems that any things which are non-identical are not the same being. Thus, van Inwagen must assume that there is absolute identity, and deny that this relation holds between, say, Father and Son. Thus, van Inwagen has not demonstrated the consistency of (this version of) trinitarianism. Further, the theory doesn't rule out polytheism, as it doesn't deny that there are non-identical divine beings. In sum, the impure relative identity trinitarian must be able to tell a plausible and orthodox metaphysical story about how non-identical beings may nonetheless be “one God”, and van Inwagen hasn't done this, staying as he has in the realm of logic (Rea 2003, 441–2).

In a later discussion (van Inwagen 2003), van Inwagen goes farther, claiming that trinitarian doctrine is inconsistent “if the standard logic of identity is correct”, and denying there is any “relation that is both universally reflexive [i.e., everything bears the relation to itself] and forces indiscernibility [i.e., things standing in the relation can't differ]” (92). Thus, there's no such relation as classical or absolute identity, but there are instead only various relative identity relations (92–3). Many philosophers would object that whatever reason there is to believe in the Trinity, it is more obvious that there's such a relation as identity, that the indiscernibility of identicals is true, and that we do successfully use singular referring terms.

Another theory claims to possess the sort of metaphysical story van Inwagen's theory lacks. Based on the concept of constitution, Rea and Jeffrey Brower develop a three-self Trinity theory according to which each of the divine persons is non-identical to the others, as well as to God, but is nonetheless “numerically the same” as all of them (Brower and Rea 2005a; Rea 2009; Rea 2011). They employ an analogy between the Christian God and material objects. When we look at a bronze statue of Athena, they urge, we should say that we're viewing one material object. Yet, we can distinguish the lump of bronze from the statue. These cannot be identical, as they differ (e.g., the lump could, but the statue couldn't survive being smashed flat). We should say that the lump and statue stand in a relation of “accidental sameness”. This means that they needn't be, but in fact are “numerically the same” without being identical. While they are numerically one physical object, they are two hylomorphic compounds, that is, two compounds of form and matter, sharing their matter. This, they hold, is a plausible solution to the problem of material constitution (Rea 1995).

Similarly, they argue, the persons of the Trinity are so many selves constituted by the same stuff (or something analogous to a stuff). These selves, like the lump and statue, are numerically the same without being identical, but they don't stand in a relation of accidental sameness, as they could not fail to be related in this way. Father, Son, and Spirit are three quasi form-matter compounds. The forms are properties like “being the Father, being the Son, and being the Spirit; or perhaps being Unbegotten, being Begotten and Proceeding” (Rea 2009, 419). The single subject of those properties is “something that plays the role of matter,” which Rea calls “the divine essence” or “the divine nature” (Brower and Rea 2005a, 68; Rea 2009, 420). Whereas in the earlier discussion “the divine essence [is] not… an individual thing in its own right” (Brower and Rea 2005a, 68; cf. Craig 2005, 79), in a later piece, Rea holds the divine nature to be a substance (i.e. an entity, an individual being), and moreover “numerically the same” substance as each of the three. Thus, it isn't a fourth substance; nor is it a fourth divine person, as it isn't, like each of the three, a form-(quasi-)matter compound, but only something analogous to a lump of matter, something which constitutes each of the Three (Rea 2009, 420; Rea 2011, section 6). Rea adds that this divine nature is a fundamental power which is sharable and multiply locatable. He does't say whether it is either universal or particular, saying, “I am unsure whether I buy into the universal/particular distinction” (Rea 2011, section 6). All properties, in his view, are powers, and vice versa. Thus, this divine nature is both a power and a property, and it plays a role like that of matter in the Trinity.

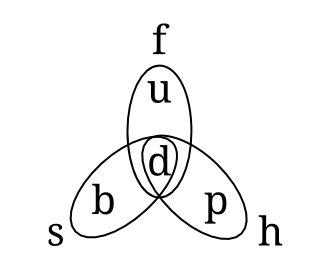

This three-self theory, which has been called Constitution Trinitarianism, may be illustrated as follows (Tuggy 2013a, 134).

There are seven realities here, none of which is (absolutely) identical to any of the others. Four of them are properties: the divine nature (d), being unbegotten (u), being begotten (b), and proceeding (p). Three are hylomorphic (form-quasi-matter) compounds: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (f, s, h) – each with the property d playing the role of matter within it, and each having its own additional property (respectively: u, b, and p) playing the role of form within it. Each of these compounds is a divine self. The ovals can be taken to represent the three hylomorphs (form-matter compounds) or the three hylomorphic compounding relations which obtain among the seven realities posited by CT. Three of these seven (f, s, h) are to be counted as one god, because they are hylomorphs with only one divine nature (d) between them. Thus, of the seven items, three are properties (u, b, p), three are substances which are hylomorphic compounds (f, s, h), and one is both a property and a substance, but a simple substance, not a compound one (d).

Brower and Rea argue that their theory stands a better chance of being orthodox than its competitors, and point out that a part of their motivation is that leading medieval trinitarians such as Augustine, Anselm, and Aquinas say things which seem to require a concept of numerical sameness without identity. (See Marenbon 2007, Brower 2005, and the supplementary document on the history of Trinity theories, sections 3.3.2, on Augustine, and 4.1, on Thomas Aquinas.)

In contrast to other relative-identity theories, this theory seems well-motivated, for its authors can point to something outside trinitarian theology which requires the controversial concept of numerical sameness without identity. This concept, they can argue, was not concocted solely acquit the trinitarian of inconsistency. But this strength is also its weakness, for on the level of metaphysics, much hostility to the theory is due to the fact that philosophers are heavily divided on the plausibility of a constitution-based solution to the problem of material constitution. A Trinity theory, these philosophers think, can gain no support from a wrongheaded metaphysics of material objects.

This Constitution theory has been criticized as underdeveloped, unclear in its aims, unintelligible, incompatible with self-evident truths, unorthodox relative to Roman Catholicism, polytheistic and not monotheistic, not truly trinitarian, out of step with the broad historical catholic tradition, implying that the persons of the Trinity can't simultaneously differ in intrinsic properties, and as wrongly implying that terms like “God” are systematically ambiguous (Craig 2005; Hasker 2010b; Hughes 2009; Pruss 2009, Tuggy 2013a).

2.2 20th Century Theologians and “Social” Theories

Some influential 20th-century theologians interpreted the Trinity as containing just one self. (See section 1.3 above.) In the second half of the century, many theologians reacted against one-self theories, criticizing them as modalist or as somehow near-modalist. This period also saw the wide and often uncritical adoption of a paradigm for classifying Trinity theories which derives from 19th c. French Catholic theologian Théodore de Régnon (Barnes 1995). On this widely adopted paradigm, Western or Latin or Augustinian theories are contrasted with Eastern or Greek or Cappadocian theories, and the difference between the camps is said to be merely one of emphasis or “starting point.” The Western theories, it is said, emphasize or “start with” God's oneness, and try to show how God is also three, whereas the Eastern theories emphasize or “start with” God's threeness, and try to show how God is also one. The two are thought to emphasize, respectively, psychological or social analogies for understanding the Trinity, and so the latter is often called “social”trinitarianism. But this paradigm has been criticized as confused, unhelpful, and simply not accurate to the history of Trinitarian theology (Cross 2002, 2009; Holmes 2012).

Although the language of Latin vs. “social” Trinity theories has been adopted by analytic philosophers (e.g. Leftow 1999; Hasker 2010c; Tuggy 2003), these have interpreted the different theories as logically inconsistent (i.e. such as both can't be true), and not merely differing in style, emphasis, or sequence.

Numerous 20th century theological sources, accepting the de Régnon paradigm, proceed to blame the Western tradition for “overemphasizing the oneness” of God, and recommend that balance may be restored by looking to the Eastern tradition. A number of concerns characterize theologians in this 20th and 21st century movement of “social” trinitarianism:

- Preserving genuinely interpersonal relationships between the members of the Trinity, particularly the Father and the Son.

- Doing justice to the New Testament idea of Christ as a personal mediator between God and humankind.

- Suspicion that the “static” categories of Greek philosophy have in previous trinitarian theology obscured the dynamic and personal nature of the triune God.

- Concern that traditional or Western trinitarian theology has made the doctrine irrelevant to practical concerns such as politics, gender relations, and family life.

- The idea that to be Love itself, or for God to be perfectly loving, God must contain three subjects or persons (or at any rate, more than one). (See 2.3 and 2.5 below.)

(For surveys of this literature see Kärkkäinen 2007; Olson and Hall 2002, 95–115; Peters 1993, 103–45.) Writers are often unclear about what Trinity theory they're endorsing. The views seem to range from tritheism, to the idea that the Trinity is an event, to something that differs only slightly, or only in emphasis, from pro-Nicene (see section 3.3 of the supplementary document on the history of trinitarian doctrines) or one-self theories. Merricks observes that some views advertised as “social trinitarianism” make it “sound equivalent to the thesis the Doctrine of the Trinity is true but modalism is false” (Merricks 2006, 306). However, a number of Christian philosophers, and some theologians employing the methods of analytic philosophy, have taken a starting point in this literature and developed clear three-self Trinity theories, which are surveyed here. They differ in how they claim to secure monotheism (Leftow 1999).

2.3 Functional Monotheism

A three-self trinitarian may argue that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are one God because of how they function, how they relate to each other, and to everything else. The best developed theory like this is by Richard Swinburne, who argues that it is uncharitable to read the ecumenical councils' claim that “there is only one god” as asserting that there's only one divine individual, as that would contradict their commitment to there being three divine individuals. He suggests that they should be read as “denying that there were three independent divine beings, any one of which could exist without the other; or which could act independently of each other” (Swinburne 1994, 180, original emphasis). He holds that each of the three “is God” in the sense that each possesses all the divine attributes. He summarizes his trinitarian theory as follows.

…the three divine individuals taken together would form a collective source of the being of all other things; the members would be totally mutually dependent and necessarily jointly behind each other's acts. This collective [i.e., the Christian God] would be indivisible in its being for logical reasons—that is, the kind of being that it would be is such that each of its members is necessarily everlasting, and would not have existed unless it had brought about or been brought about by the others. The collective would also be indivisible in its causal action in the sense that each would back totally the causal action of the others. The collective would be causeless and so (in my sense), unlike its members, ontologically necessary, not dependent for its existence on anything outside itself. It is they, however, rather than it, who, to speak strictly, would have the divine properties of omnipotence, omniscience, etc…. Similarly this very strong unity of the collective would make it, as well as its individual members, an appropriate object of worship. (1994, 180–1)

As he understands the concept of substance, the Trinity, referred to above as “the collective”, is a substance, one with divine substances as parts, but is not itself a divine substance or person. He hastens to add, though, that by a natural extension of use we may say of the Trinity what we say of the persons, e.g., that it is all-powerful, all-knowing, etc. (9–13, 181).

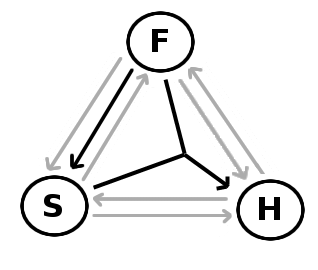

For Swinburne an “ontologically necessary” substance is one which exists everlastingly with no active or permissive cause for its existence. A “metaphysically necessary” substance is one which is either ontologically necessary or such that it everlastingly exists, and at least the start of its existence is due to the inevitable action of some other being which is uncaused and everlasting (118, 146). He rejects the view, popular among theists, that a divine being must be a se (i.e., must exist through or because of itself) in the sense of ontological necessity, arguing that it is simpler and more reasonable to attribute only metaphysical necessity to them (118–21, 170–80). In his view, each of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit is metaphysically necessary, as the Father is the active cause of the Son, and the Father and Son together actively co-cause the Spirit. (He remains neutral about whether this active causation is eternal or only for the first portion of the Son's and of the Spirit's existence, and he seems not to regard co-causing as involving causal overdetermination.) Each of the three, being omnipotent, must also be a permissive cause of the existence of each of the other two. The following chart illustrates how the persons of the Trinity are related to one another in Swinburne's theory. The black arrows represent active causation, and the gray arrows represent permissive causation.

The Father has a kind of priority, and this gives him authority to lay down some rules which when agreed to will prevent the wills of these three omnipotent beings from ever clashing (171–5). In sum, the Trinity is a tightly unified complex thing with three divine beings as parts, which necessarily acts much as a single personal being would. It is a whole, which is, in a sense, reducible to the sum of its parts; the entire set of truths about the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit could in principle be stated without mentioning this collective or composite which is the Trinity (10, 13).

Swinburne believes it can be shown probable that a god exists, and he also argues that “the most probable kind of God is such that inevitably he becomes tripersonal” (1994, 191). More precisely, he argues that if it is possible for there to be more than one divine person, there will of necessity be exactly three. A divine person, he argues, being all-knowing and perfectly good, will recognize the supreme value of love.

Love involves sharing, giving to the other what of one's own is good for him and receiving from the other what of his is good for one; and love involves co-operating with another to benefit third parties. (177)

Inevitably, then, the first divine being will produce another, then inevitably cooperate with that being to produce a third, and also inevitably, each of the three will freely allow the other two to continue to exist (being divine and thus omnipotent and perfectly free, each must freely give his permission if anything else is to exist). Thereafter, inevitably, each being will cooperate in whatever either of the others does. Why not a fourth? No qualitative difference in the loving would result therefrom, or at least not a difference that would bring about a over-riding reason for anyone to create a fourth, and so no divine being would, by its essential nature, inevitably bring about a fourth (etc.). And a divine being can't be created by an act of will (rather than an act of essence), as this would imply that it could possibly not exist, which is incompatible with its being divine (177–9).

In a sympathetic but penetrating critique, William Alston highlights some difficulties for the above theory stemming from Swinburne's ideas of metaphysical and ontological necessity. First, Alston says, “I can find no reason, or even motivation, for Swinburne's making ontological necessity one of the ways of being metaphysically necessary” (Alston 1997, 41). One might even say that the theory is arbitrarily rigged so that may say of both the Trinity and each of the persons, that they are all “necessary”. Alston worries that this in fact represents “a considerable weakening of the unity of the divine nature”, as it has been bought cheaply with a disjunctive definition (53). Second, while Swinburne wants to say that an ontologically necessary being and a (merely) metaphysically necessary being are “equally ultimate”, it seems that the former would be more ultimate. And while both sorts of being are supposed to exist inevitably, a (merely) metaphysically necessary being won't, unless its cause's existence and causal action are also necessary (42–3). Third, more seriously, on Swinburne's definition, none of the three persons of the Trinity (contrary to his intention) is metaphysically necessary, for none is ontologically necessary, and none is caused by an uncaused individual, as each has two permissive causes, namely, the other two persons of the Trinity (Alston 1997, 42–9). Based on conversations with Swinburne, Alston suggests that to satisfy his theoretical aims, Swinburne needs the following revised definition:

A substance S1 is metaphysically necessary if either (1) it is ontologically necessary, or (2) it is everlasting and has no active cause of its existence throughout some first (beginningless) period of time, or (3) it is everlasting and is (directly or indirectly actively caused to exist through some first (beginningless) period of time by a cause whose backwardly everlasting existence has no active cause, inevitably so in virtue of its properties. And any cause of the existence of a type (2) or type (3) being at any time is either (a) one whose backwardly everlasting existence has no active cause, or (b) one of which any cause either has no active cause for its backwardly everlasting existence or is such that none of its causes has any active cause for its backwardly everlasting existence, or… (51, original emphases)

Thus, the special priority of the Father is preserved, in that but for his action, the other two wouldn't exist, whereas his existence doesn't depend on any being's causal activity (52). As to the charge of tritheism, Alston opines that “Swinburne embraces a fairly straightforward form of tritheism” (55). He adds however, that anyone seeking to make the doctrine intelligible, is inevitably going to tilt towards either modalism or tritheism. He suggests that Swinburne's real error lies in his attempt to make the doctrine intelligible at all, which robs the doctrine of its mystery, turning it into “something that any bright philosophy or theology student can clearly grasp here and now”, rather than something that will be understood only “when we see the Triune God face to face” (56; cf. Alston 2005 and section 3 below).

Other critics have been less sympathetic. Brian Leftow objects that in Swinburne's account God is not itself divine. Nor does it makes sense to worship it, as it is not the sort of thing which can be aware of our addressing it. Further, the issue of monotheism isn't the issue of how unified the divine beings are, but rather of how many. And it stretches credibility to interpret the creed's claim that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are “one God” to tell us how the three divine beings act. Rather, three persons are numbered in the creeds, but they are said to be only one God. Moreover,

…it is hardly plausible that Greek paganism would have been a form of monotheism had Zeus & Co. been more alike, better behaved, and linked by the right causal connections. (Leftow 1999, 232; cf. Rea 2006)

Moreover, if Swinburne were right, it would be coherent to suppose that both monotheism were true, and that there were an infinity of gods. But that is not coherent (233–4). While one might argue that gods who necessarily act in a unified manner would give us all we care about in monotheism, Leftow argues that this isn't so, as the Bible asserts the existence of precisely one god (235–6). Swinburne's theory entails serious inequalities of power among the Three, jeopardizes the personhood of each, and carries the serious price of allowing (contrary to most theists) that a divine being may be created, and the possibility of more than one divine being (236–40). Using familial analogies, Leftow challenges Swinburne's claim that the Three would lack an overriding reason to produce a fourth, noting that “Cooperating with two to love yet another is a greater “balancing act” than cooperating with one to love yet another” (241).

Dale Tuggy objects that a priori arguments for a Trinity of divine selves, like those of Swinburne, Stephen T. Davis, and Richard of St. Victor (d. 1173) fail to show the impossibility of a single perfect self (Tuggy 2013c; Richard of St. Victor 1979; also see section 2.5 below).

Kelly Clark criticizes Swinburne's theory on four main counts. First, the reasons given for affirming metaphysical rather than ontological necessity of divine beings are unconvincing (Clark 1996, 465–7, 474). Second, the omniscience and omnipotence of the three divine persons would necessarily prevent any clash of wills, rendering Swinburne's postulation of a kind of governing authority exercised by the Father unnecessary (467–70). Third, his position is tritheism. Finally, his readings are not the overall best interpretations of the Nicene and “Athanasian” creeds (471–3).

Tuggy (2004) objects that if this theory were true, it would seem that one or more members of the Trinity had wrongfully deceived us by leading us to falsely believe that there is only one divine self. He also argues that the New Testament writings assume that “God” and “the Father of Jesus” (in all but a few cases) co-refer, so that God and the Father are assumed to be identical. Denying this last claim, he argues, amounts to an uncharitable and unreasonable attribution of a serious confusion to the New Testament writers and (if they're believed) to Jesus as well. These arguments are rebutted by William Hasker (2009) and the argument is continued in Hasker 2011 and Tuggy 2011b.

2.4 Trinity Monotheism

The Trinity monotheist says there is one God because there is one Trinity (Moreland and Craig 2003, 575–96; Craig 2006). Unlike those in the pro-Nicene tradition, they aim to provide a literal model:

God is an immaterial substance or soul endowed with three sets of cognitive faculties each of which is sufficient for personhood, so that God has three centers of self-consciousness, intentionality, and will…. the persons are [each] divine… since the model describes a God who is tri-personal. The persons are the minds of God. (Craig 2006, 101)

Only the Trinity, on this theory, is an instance of the divine nature, as the divine nature includes the property of being triune; beyond the Trinity “there are no other instances of the divine nature” (2003, 590). So if “being divine” means “being identical with a divinity” (i.e., being a thing which instantiates the nature divinity), then none of the persons are “divine”. But they don't put it that way. They say that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are each “divine” in another sense. They compare the Trinity to the mythical three-headed dog Cerberus, arguing that just as this beast is one dog because it has one body, so the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are one God because they are three centers of consciousness in one soul (2003, 393).

Daniel Howard-Snyder (2003) offers numerous objections, some of which are as follows. They can't avoid either polytheism or different levels of divinity, either of which would make their theory (contrary to their intentions) unorthodox. The Cerberus analogy is criticized on the grounds that it would be not one dog with three minds, but rather, three dogs with overlapping bodies. They uphold (with the creeds) one divine substance, and yet by their own criteria each of the three persons must be a substance as well, and they hold that each person is divine. Thus, they seem saddled with polytheism (393–5). In their view God is not a personal being, in the sense of being numerically identical with a certain self, even though it (God) has parts which are selves. They want to say, for example, that each of the three is all-knowing, and they also want to say God is all-knowing, in that he has parts which are all-knowing. But Howard-Snyder objects that,

…there can be no “lending” of a property [i.e., a whole “getting” a property from one of its parts] unless the borrower is antecedently the sort of thing that can have it….[Therefore,] Unless God is antecedently the sort of thing that can act intentionally—that is, unless God is a person—God cannot borrow the property of creating the heavens and the earth from the Son….All other [statements involving] acts attributed to God [in the Bible] will likewise turn out to be, strictly and literally, false. (399–400)

In their view, a thing (God) can exemplify the divine nature without itself being a (identical to) a self. Nor can divinity include properties which require being a self, e.g., being all-knowing, being perfectly free. This, he argues, is “an abysmally low” view of the divine nature, as “If God is not a person or agent, then God does not know anything, cannot act, cannot choose, cannot be morally good, cannot be worthy of worship” (401).

Craig replies to Howard-Snyder's objection to the Cerberus analogy that the claim that it represents three dogs is “astonishing”, as we all speak of two headed snakes, turtles and such (Craig 2003, 102). While on Trinity monotheism God isn't identical to any personal being, it doesn't follow that God isn't “personal”. He is personal in the sense of having personal parts. Further, the view that God isn't a self

is part and parcel of Trinitarian orthodoxy….Howard-Snyder assumes that God cannot have such properties [i.e., knowledge, choice, moral goodness, worship-worthiness] unless He is a person. But it seems to me that God can have them if God is a soul possessing the rational faculties sufficient for personhood. If God were a soul endowed with a single set of rational faculties, then He could do all these things. By being a more richly endowed soul, is God thereby somehow incapacitated? (105)

As to the charge of polytheism, he accuses Howard-Snyder of confusing monotheism with unitarianism (106). Finally, Craig argues that the issue of whether or not the Three count as parts of God is unimportant (107–13). Tuggy (2013b) presses some of Howard-Snyder's objections, concluding that the theory is either not monotheistic, or turns out to be a one-self theory.

2.5 Perichoretic Monotheism

Stephen T. Davis (1999, 2003, 2006) gives a philosophical argument for there being more than one divine self. God must be perfect in love, which requires that he loves another. But it is possible that only God exists. Either “social” (i.e. multiple-self) trinitarianism is true, or “there is no ‘other’ in the Godhead” (2006, 65). But there must be an “other” in the divine nature, therefore multi-self trinitarianism is true (2006, 65–8; Davis 1999). Unlike Swinburne's argument, this one doesn't involve divine persons causing others to exist. Also, it is strictly speaking not an argument for three-self trinitarianism, as it only tries to prove that there is more than one thing capable of loving and being loved within the divine nature (Davis 2006, 66–8). (For objections to such arguments see section 2.3 above.)

Davis holds that there are three selves which are essentially and equally divine. None is a cause of any other. These three differ “primarily and pre-eminently in their relations to each other” (Davis 2006, 71). The Father “begets” the Son, and these two bear a different relation to the Spirit; but these relations are not causal, but only logical. Whatever any of the three selves does respecting the rest of reality, the other two in some sense do as well, and they are not capable of disagreeing. God is personal (God in some sense contains three persons) but isn't strictly speaking a self (Davis 2006, 69–71). God just is (identical to) the divine nature or godhead (2006, 75).

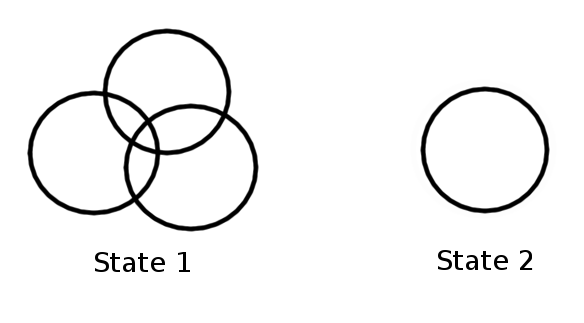

Why is this a form of monotheism rather than tritheism? Davis mentions their equally possessing the divine essence, and their inability to disagree, but for him the main factor is that the three enjoy the relation of perichoresis, which he expounds as meaning “co-inherence, mutual indwelling, interpenetrating, merging” (2006, 72). It has been objected that the concept of perichoresis is too unclear to help us see why three divine persons should be one God (Tuggy 2003, 170–1). Davis admits the unclarity, but appeals to the pro-Nicene tradition of giving admittedly inadequate analogies for the Trinity (2006, 72). (See section 3.3 in the supplementary document on the history of Trinity theories.) He invites us to imagine the contradictory situation of three circles being simultaneously in State 1 and in State 2 (2 representing them as “stacked” or circumscribing the same area).

In State 2, we may truly say there are three circles, that there's one circle, or that there are three-in-one, but we may not say there are four (Davis 2006, 73). To the objection that this example is contradictory, he replies that he's not trying to give a consistent model of the Trinity, but only explicating the meaning of perichoresis. The Trinity is “at bottom mysterious” (73–4).

William Hasker's three-self theory is similar to Davis's, although Hasker isn't as quick to appeal to mystery. Like Davis, he mentions nature-sharing, necessary cooperation, generation and procession, perichoresis, and he adds “a single divine mind with three personal centers of consciousness, knowledge, and will” in the attempt to show his theory to be monotheistic (Hasker 2013, number 7). Tuggy (2013b) argues that Hasker fails to show this.

2.6 Group Mind Monotheism

Brian Leftow explores the answer, found in some twentieth century theologians, but not much defended in recent philosophical theology, that the three persons are one God because “the Trinity has or is a divine mind composed of the Persons' minds” (1999, 221). Some have suggested that for all we know, all human minds are group minds. As support, they appeal to commissurotomy patients who after their brain hemispheres are divided seem to act as if each half were itself a functioning mind. But then, perhaps, the normal human brain supports a group mind composed of the minds associated with each half.

Granting that it's possible for there to be group minds, Leftow argues that this concept will be no help to the social trinitarian. Thinking of a group mind as a fourth mind emerging from the three divine minds will result in too many divine minds (four). On the other hand, we might think of the Trinity's mind as God's “real” mind, the three others being sub-minds. But this would render the persons of the Trinity less than persons, incapable of truly inter-personal relationships (thus clashing with a major motivation of any social trinitarian theory) (Leftow 1999, 221–4).

C. J. F. Williams tries to avoid this dilemma by positing that the three divine minds share one set of mental states (Williams 1994, 242; Leftow 1999, 224–7). Leftow objects that we have no idea whether or not this is possible (non-contradictory), as we don't know what, if anything, would preserve the distinctness of the minds. Other puzzles arise concerning God and self-reference. Suppose God thinks “I exist”. What does the term “I” refer to there? Not the Trinity, as it is the persons in whom this thought inheres, and on this theory the Trinity is not identical to any of the persons. But as it inheres equally in each of the persons, it is not clear (as orthodoxy and the New Testament would seem to demand) that each person is able to refer to himself alone or be the primary actor in certain actions (e.g., becoming incarnate, dying on a cross) (Leftow 1999, 225–6).

2.7 Material Monotheism

Christopher Hughes suggests a theory much like the Constitution theory (section 2.1.2 above) but without its controversial claim that there can be numerical sameness without identity. On this picture,

we have just one (bit of?) divine “matter,” three divine forms, and three (“partially overlapping,” materially indiscernible but formally discernible divine hylomorphs [compounds of form and matter]. …“divine person” is true of the three hylomorphs, but… “God” is true of the (one and only) (bit of?) “divine matter.” (Hughes 2009, 309)

On this theory, “The Father is God,” means that the Father has God for his matter, or that the Father is “materiated by” God, and “The Father is the same God as the Son” means that these two are materiated by the same God (309–10).

An obvious objection is that the one God of Christianity is not supposed to be a portion of matter. Hughes replies that perhaps it is orthodox to say that God is a very unusual kind of matter (310).

Alternately, Hughes suggests a retreat from matter terminology, and argues that persons of the Trinity can't bear the same relation they bear to one another that each bears to God. That is, it can't be correct, for example, that Father and Son are consubstantial, and that the Father and God are consubstantial. The reason is that for two things to be consubstantial is for there to be something which both are “substantiated” or “ensubstanced” by. They are consubstantial because they both bear this other relation to a third, substantiating thing. Thus, e.g. “The Father is God” means “The Father is (a person of the substance) God.” Thus, even though Father and Son are numerically two, still it can be true that “There is just one (substance) God” (311).

On this alternate view, though, what does it mean to say that God is the substance of a divine person? Hughes suggests that the case is analogous to material objects. A sweater and some wool thread are “co-materiate” in that both are “materiated” or “enmattered” by one portion of matter, though they are numerically distinct (311; cf. 313). Hughes suggests it is an open question whether this is a different theory, or just a restatement of the first “in more traditional theological terminology.” It will be the latter “If we can stretch the notion of ‘matter’ far enough to cover God, and stretch the notion of material substance (aka hylomorph) far enough to cover the divine persons” (312). Hughes ends on a negative mysterian note (see section 3 below), claiming that it is an advantage of this last account that ensubstancement is “a (very, though not entirely) mysterious relation” (313).

This view has not been discussed in the literature, but obvious objections would include: that the Christian God is neither literally nor analogous to a portion of matter, that the doctrine is inconsistent with divine simplicity, and that it inconsistent with any person of the Trinity being fully divine, because full divinity requires aseity, which is inconsistent with being a hylomorph.

2.8 Concept-relative Monotheism

Einar Duenger Bøhn (2011) argues that trinitarian problems of self-consistency vanish when one realizes that the Trinity “is just an ordinary case of one-many identity” (363). He takes from Frege the idea that number-properties are concept-relative. Thus,

conceptualizing the portion of reality that is God as the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, we have conceptualized it as being three in number, but it is nonetheless the same portion of reality as what we might conceptualize as God, and hence as being one in number. (366)

There is no privileged way of conceptualizing [this portion of reality] in terms of which we can explain the other way. Both ways are equally legitimate. (369)

Most philosophers don't think there can be one-many identity relations. Some think it is of necessity a one-one relation, though many allow there can be many-many identity; for instance, it may be that the three men who committed the robbery are identical to the three men who were convicted of the robbery. Those who believe identity can be one-many typically do so because they accept the controversial thesis that composition (the relation of parts to a whole they compose) should be understood as identity. Though Bøhn does accept that thesis (Bøhn 2013), he argues that this Trinity theory relies only on our having “a primitive notion of plural identity” (371), that is, a concept we understand without reference to any concept from mereological (parts and wholes) theory. For example says we can recognize a certain human body to be identical to a certain plurality of head, torso, two arms, and two legs. And we can recognize that a pair of shoes is identical to a plurality of shoes (365).

Bøhn argues that orthodoxy, by the standards of either the New Testament or the “Athanasian” Creed, requires that the persons of the Trinity be distinct (i.e. no one is identical to any other) but not that any is identical to the one God. Rather, orthodoxy requires that the one God is identical to the Three considered as a plurality. Thus, e.g. “The Father is God” must be read predicatively, that is, not as identifying the Father with God, but rather as describing the Father as divine (364, 367 n. 13).

Does this theory make God's triunity dependent on human thought? And might the divine portion of reality equally well be conceived as seventeen? Bøhn replies,

That numerical properties are relational properties with concepts as their relational units is compatible with reality having a real and objective numerical structure. (372)

Thus, it doesn't follow that any conceptualization of this portion of reality is equally correct. While in this context he demurs from saying anything about concepts (372), it seems that Bøhn assumes in Fregean fashion that concepts are objective and not mind-dependent (Bøhn 2013, section 1).

This theory has not been discussed in the literature. It is not easy to see the motivation for thinking, for example, that a body can be identical to a head, a torso, two arms and two legs, unless one accepts that identity is composition. Again, more should be said about what “concepts” are. And if the correctness of a description depends on “objective structure” in the world, is that compatible with the claim that all “numerical ascriptions are simply incomplete independent of or prior to… a legitimate conceptualization of [that] portion of reality”? (371)

Sheiva Kleinschmidt argues that theories on which composition is explained in terms of identity are of no use to the trinitarian, for such theories add no significant options to the options the trinitarian already has (Kleinschmidt 2012).

2.9 Temporal Parts Monotheism

Harriet Baber (2002) argues that a Trinity theory may posit the “persons” as “successive, non-overlapping temporal parts of one God” (11). This one God is neither simple nor timeless, but is a temporally extended self with other, shorter-lived temporally extended selves as his parts. This does not violate the requirement of monotheism, because we should count gods by “tensed identity”, which is “not identity but rather the relation that obtains between individuals at a time, t, when they share a stage [i.e. a temporal part] at t” (5). At any given time, only one self bears this relation of temporal-stage sharing with God.

How can any of these selves be divine given that they are neither timeless nor everlasting? Following Parfit, she argues that a self may last through time without being identical to any later self at the later times; that is, “identity is not what matters for survival”(6) Each of these non-eternal selves, then, counts as the continuation of the previous one, and is everlasting in the sense that it is a temporal part of an everlasting whole, God. The obscure traditional generation and procession are re-interpreted as non-causal relations between God and two of his temporal parts, the Son and Spirit (13–4). In a later paper, she argues that any trinitarian may and should accept this re-interpretation (Baber 2008).

Although Baber argues that this theory is a “minimally decent” Trinity theory, she admits that it is heretical, and names it a “Neo-Sabellian” theory, because on it, the persons of the Trinity are non-overlapping, temporary modes of the one God (15; on Sabellianism see section 1 above). But the “persons” in this theory are not mere modes; they are truly substances and selves, and there are (at least) three of them, though each is counted as the continuation of the one(s) preceding him. It is unclear whether the theory posits only three selves (10–1). But she argues that the theory is preferable to many of its rivals “since it does not commit us to relative identity or require any ad hoc philosophical commitments” (15), and since even though its divine selves don't overlap, sense can be made of, e.g. Jesus's interaction with his Father (meaning not the prior divine person, but God, the temporal whole of whom Jesus is a temporal part) (11–4).

While this theory has not been discussed in the literature, it is notable in being a case not of rational reconstruction, but of doctrinal revision (Tuggy 2011a). Many features of it are controversial, such as its unorthodoxy, its metaphysical commitments to temporal parts and the lasting of selves without diachronic identity, its denials of divine simplicity and divine timeless, and its redefinitions of “monotheism”, “generation”, and “procession”.

3. Mysterianism

Often “mystery” is used in a merely honorific sense, meaning a great and important truth or thing relating to religion. In this vein it's often said that the doctrine of the Trinity is a mystery to be adored, rather than a problem to be solved. In the Bible a “mystery” (Greek: musterion) is simply a truth or thing which is or has been somehow hidden (i.e., rendered unknowable) by God (Anonymous 1691; Toulmin 1791b). In this sense a “revealed mystery” is a contradiction in terms (Whitby, Hysterai, 101–9). While Paul seems to mainly use “mystery” for what used to be hidden but is now known (Tuggy 2003, 175), it has been argued that Paul assumes that what has been revealed will continue to be in some sense “mysterious” (Boyer 2007, 98–101).

Mysterianism is a meta-theory of the Trinity, that is, a theory about trinitarian theories, to the effect that an acceptable Trinity theory must, given our present epistemic limitations, to some degree lack understandable content. “Understandable content” here means propositions expressed by language which the hearer “grasps” or understands the meaning of, and which seem to her to be consistent.

At its extreme, a mysterian may hold that no first-order theory of the Trinity is possible, so we must be content with delineating a consistent “grammar of discourse” about the Trinity, i.e., policies about what should and shouldn't be said about it. In this extreme form, mysterianism may be a sort of sophisticated position by itself—to the effect that one repeats the creedal formulas and refuses on principle to explain how, if at all, one interprets them. More common is a moderate form, where mysterianism supplements a Trinity theory which has some understandable content, but which is vague or otherwise problematic. Thus, mysterianism is commonly held as a supplement to one of the theories of sections 1 and 2 above. Again, it may serve as a supplement not to a full-blown theory (i.e., to a literal model of the Trinity) but rather to one or more (admittedly not very helpful) analogies. (See section 3.3.1 in the supplementary document on the history of trinitarian doctrines.) Unitarian views on the Trinity are often partially motivated by hostility to mysterianism. (See the supplementary document on unitarianism.)

Mysterians view their stance as an exercise of theological sophistication and epistemic humility. Some mysterians appeal to the medieval tradition of apophatic or negative theology, the view that one can understand say what God is not, but not what God is, while others simply appeal to the idea that the human mind is ill-equipped to think about transcendent realities.

Tuggy lists five different meanings of “mystery” in the literature:

[1]…a truth formerly unknown, and perhaps undiscoverable by unaided human reason, but which has now been revealed by God and is known to some… [2] something we don't completely understand… [3] some fact we can't explain, or can't fully or adequately explain… [4] an unintelligible doctrine, the meaning of which can't be grasped….[5] a truth which one should believe even though it seems, even after careful reflection, to be impossible and/or contradictory and thus false. (Tuggy 2003, 175–6)

Sophisticated mysterians about the Trinity appeal to “mysteries” in the fourth and fifth senses. The common core of meaning between them is that a “mystery” is a doctrine which is (to some degree) not understood, in the sense explained above. We here call those who call the Trinity a mystery in the fourth sense “negative mysterians” and those who call it a mystery in the fifth sense “positive mysterians”. It is most common for theologians to combine the two views, though usually one or the other is emphasized.

Sophisticated latter-day mysterians include Leibniz and the theologian Moses Stuart (1780–1852). (See Antognazza 2007; Leibniz Theodicy, 73–122; Stuart 1834, 26–50.)

3.1 Negative Mysterianism